Beyonce takes a jackhammer to Nashville with country album, Cowboy Carter

Beyonce ain’t the first artist to explore the genre, but Cowboy Carter represents a strident challenge to corporate country’s inherent racism.

According to the script, Beyonce’s new album sees the former Destiny’s Child singer “go country”.

But does Cowboy Carter, due out March 29, represent the seismic career shift and industry-disrupting rodeo that many are heralding?

Yessir, in some small ways. No ma’am, in a much more fundamental sense.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Cowboy Carter, and guitar twangin’ singles like Texas Hold ‘Em and 16 Carriages, are only groundbreaking insofar as black music’s often sterling examples of recorded country music have been all but paved over by a country music industry seemingly motivated to maintain long-established racial divides.

Queen Bey has “simply” taken a jackhammer to the asphalt on Nashville’s Music Row.

“This ain’t a Country album,” she said of Cowboy Carter when she recently revealed the album’s artwork. “This is a ‘Beyonce’ album’.”

Bey added that she took her time to “bend and blend genres” together on a follow-up to 2022’s Renaissance that seems designed to ruffle tassels.

The past 100 years have seen an interplay, a whispered dialogue between country and so-called black music forms, such as rhythm and blues and rock’n’roll, and more recently hip-hop and R&B (Beyonce’s approved wheelhouse.)

That her married surname is Carter offers a neat connection to the Carter Family, whose early country tunes of the 1920s “borrowed” melodies and rhythms from the hymns of the black churches of the American South.

Black artists such as Lesley Riddle and Rufus Payne can be heard via the songbooks of the Carter Family and Hank Williams.

Fun fact, trainspotters, the first ever artist to play the revered stage of the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville — the Vatican of country music — was African-American harmonica player DeFord Bailey.

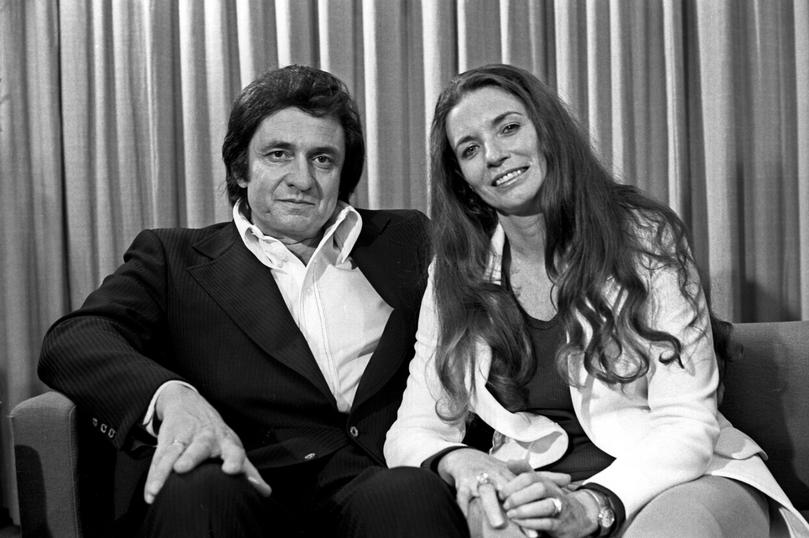

Later, outlaw country legend Johnny Cash was blatant in his B-side turned hit, Get Rhythm, which explicitly mentioned rhythm and blues (“get rhythm, when you get the blues”) in his un-woke ditty about a shoe-shine “boy” who rises above any sadness about his station in life thanks to a catchy tune.

The Man in Black, of course, married June Carter of the fabled Carter Family.

While I don’t feel the need to recap Elvis Presley’s deep debt to black music, the King combined country and rock’n’roll with the same ease as he mixed trans fats and barbiturates.

This ain’t a Country album. This is a ‘Beyonce’ album’.

Sixty-two years before Cowboy Carter, musical genius Ray Charles released his masterpiece, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, a collection of songs blending rhythm and blues with the contemporary Nashville Sound.

Arguably Charles’ greatest record, the 1962 album exposed a large audience to country music and inspired other artists, such as Candi Staton and Bobby Womack to explore their own mix of country and soul.

Charlie Pride was another black superstar of the counter-culture era and beyond, while the Pointer Sisters, better known for their later pop and disco hits, also performed country and recorded in Nashville.

But somehow, in the years since Pride and the Pointers, the country charts became off-limits for black artists.

Lil Nas X had to re-record Old Town Road with cheesy country star Billy Ray Cyrus before the “country rap” mega-smash of 2019 was considered for Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart.

In fact, the Billy Ray-less version would have topped that chart earlier had Billboard not quietly excised Old Town Road, claiming the song did not embrace “enough elements of today’s country music”.

That’s a real head-scratcher given “rap country” songs, like Jason Aldean’s Dirt Road Anthem, topped the country charts in 2011.

There are black artists working exclusively in the country genre. But for every Darius Rucker or Kane Brown, there are a million Luke Bryans, Morgan Wallens and Garth Brookses pumped up by Nashville’s corporate country empire.

The back-slapping that followed Luke Combs’ performance of Fast Car with Tracy Chapman, the singer and songwriter of the original 1988 version, at this year’s Grammys was deeply disingenuous.

When Combs’ version topped the Country Airplay chart in July last year, Chapman became the first black woman to score a country number one with a solo composition purely because an approved country artist covered it.

While country radio in the US virtually ignored Texas Hold ‘Em, Beyonce became the first black woman to reach the top spot on the Hot Country Songs chart, which collates data from airplay, digital sales and streaming, with the song.

Released at the same time as Texas Hold ‘Em, excellent country ballad 16 Carriages climbed to ninth on the same chart.

No doubt, Bey’s legion of fans will help Cowboy Carter to the top of the country charts, as well as the pop countdown, no matter what the good ol’ boys reckon. Nashville, Billboard and the other gatekeepers of what is and isn’t Country Music can’t stop her now.

But, as she points out herself, she’s no pioneer, no Stagecoach Mary or Della Rose from the Wild Bunch. Her achievements build on those of Ray Charles, Charlie Pride, Lesley Riddle et al.

That said, Beyonce broke some ground for herself. Her 2016 single Daddy Lessons is regarded as her first country song — but not by the Recording Academy, which refused to consider the hit in the country category at the Grammys (despite her recording a version with giants of the genre in the Chicks).

That time, she brought one song — a virtual pickaxe for all the impact it had on Country’s blacktop.

This time, she’s riding in on a big white horse, dressed in red, white and blue leathers with a big flag to plant — a whole darn album.

Yessir, Bey’s busted out the jackhammer.