THREE-MINUTE BIOGRAPHY: Jimmy Barnes, working-class man, survivor, takes to the road on Hell of a Time tour

THREE MINUTE BIOGRAPHY: For years Barnesy lived life at 11 out of 10. He’s The Working Class man. The survivor. And he’s heading back out on the road.

This could have been an obituary. By the standards of mere mortals it probably would have been.

But we are not talking about an everyday mortal. We are talking about Jimmy Barnes.

Barnesy. The Working Class Man. The survivor.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.You know what we mean. He is one of those people who for years lived life at volume 11 out of 10. Pushed into and beyond the red zone. Abandoned the off switch.

It is hard to believe that as recently as December it seemed Barnes had played his last gig after he had open-heart surgery after a bacterial infection he’d been fighting spread to his heart.

And yet, in April, Barnes, now 68, took to the stage at Bluesfest, outside Byron Bay.

“It’s good to be here,” he said after starting his set with his mega-hit Working Class Man. “It’s good to be f. . .ing anywhere.”

And that freight train heart is set to take him back out on another full-scale tour starting later this month.

His sheer will to push on through was perhaps born out of his early life.

Life in the tenement slums of 1950s Glasgow where he born James Dixon Swan on April 28, 1956, was a battle.

His father Jim was a prizefighter, and fighting was a constant theme.

In 2016 Barnes told The Daily Telegraph: “I remember the smells and streets in Glasgow. I remember the sense of fear all the time, and the cold.

“We lived in these tenements, these slums . . . They had about eight apartments in them, and one toilet downstairs in the entrance foyer.

“It was filthy. I was terrified of going down there; you couldn’t go at night because the lights were always smashed.

“I remembered the kids, my sisters, hiding my mum under a bed, battered and bruised, so my dad couldn’t find her. My dad was a quiet assassin.”

Jim and Dorothy Swan and their children, John, Jimmy, Dorothy, Linda, Lisa and Alan, moved to Elizabeth, just outside Adelaide, when Jimmy was five.

But their new life kept the worst of the old.

Home was “a horror house” with the same problems of his dad’s violence and booze.

His parents later divorced and Dorothy married Reg Barnes, who became a second father to Jimmy and his siblings, and whose name he took as his own.

But by the age of nine Jimmy was drinking; by eleven he was taking drugs. Gangs, sex, booze, violence were a part of everyday life throughout his teenage years.

Amid the chaos of Barnes’ life, music was a constant.

Barnes told Perth’s The Sunday Times: “Music is one of the places in my life where no matter what has gone on, it’s the thing that has kept me with one foot on the ground.”

“It’s been my connection to not only love and family and friends and audiences but also my connection to reality.

“There’s been times when I’ve been so wild and so smashed, where the whole world was spinning like a cyclone around me, and the only time I felt safe and in control was when I was on stage.”

At 16, Barnes was working as an apprentice on the railways, but music called.

His brother John was for a while a member of prog-rock band Fraternity, where a young Bon Scott also began to make his mark.

Around 1973 Barnes briefly sang in Fraternity.

But bigger things awaited as a local band called Orange became Cold Chisel. And Barnes’ future was set.

The Chisel years set a standard for Australian pub rock that was rarely matched.

Their 1978 debut single Khe Sanh gave us — and every pub cover band since — an instant and enduring classic based around the story of a Vietnam war veteran.

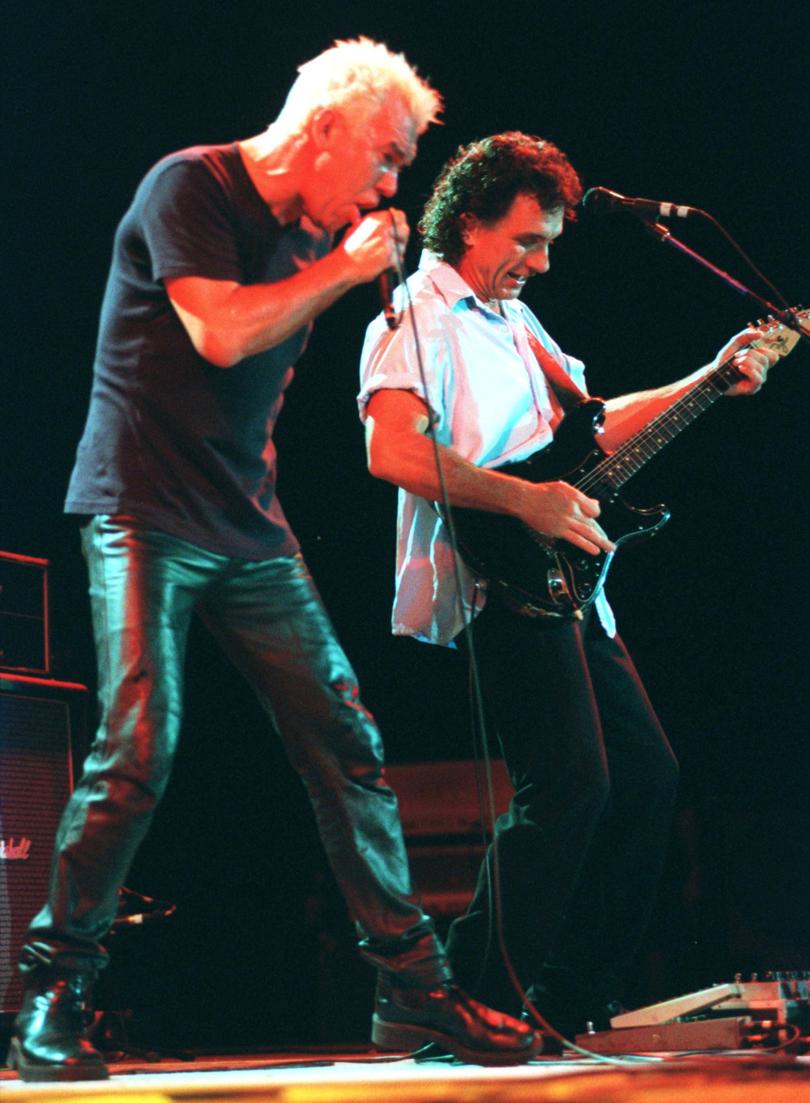

And leading the way was Barnes, a raging force driven by his demons and fuelled by vodka, hunched over his microphone, gripping it in both hands, all sweat and bulging neck veins, leaving no decibel behind.

The success and record sales mounted. And mounted. And the classics continued. Cheap Wine, Forever Now, When the War is Over and Flame Trees.

There is surely no Australian of that era who has not sung along.

After Chisel called time — for the first time — in 1983 Barnes turned into the solo Working Class Man.

He added to his CV his take on soul standards and became a best-selling author, thanks to his two deeply personal memoirs, Working Class Boy and Working Class Man.

He has notched 19 No 1 albums in Australia — more than The Beatles — and sold more records in Australia than any other local artist.

And in the ultimate sign of establishment recognition, Barnes is also an Officer of the Order Of Australia.

Many gigs in his upcoming Hell of a Time tour are sold out.

That’s a hell of a way from the raw streets of Glasgow.