Robert Redford: A classic American ideal who escaped the movie star mould

(An Appraisal)

For years, nobody seemed to do it better on-screen — more effortlessly and seductively — than Robert Redford. Blond, blue-eyed, square-jawed, with an easy smile that hinted at the fun times to come, he was the kind of big-screen ideal whom the old studio moguls prayed for and at times invented. An elevated Everyman, he could slide into any nonsensical film and somehow make it work. He could seduce a woman, ride a horse, steal a fortune, take it on the chin, slip through the shadows. Yet Hollywood fame took an abrupt turn in 1969 when he bought land in Utah’s Wasatch range that he named Sundance.

It always seemed perverse that this quintessential leading man, who died Tuesday at 89, entered the movies in the early 1960s, just as the old studio system was wheezing its final breaths. A new Hollywood was already emerging by the time he made his screen breakthrough opposite Jane Fonda in Barefoot in the Park (1967), based on the Neil Simon play and directed by Gene Saks. One of those movies whose commercial pandering stinks of desperation, it is a strained comedy about a young couple — he’s buttoned down, Fonda’s the free spirit — but its stars are undeniable, lovely, charming. (Redford originated the role on Broadway.) The whole thing is cringy and painfully stodgy, but when they’re on-screen, you don’t much care.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Redford, though, soon became one of New Hollywood’s most totemic stars. He made some good choices, notably as an outlaw in the Western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). Directed by George Roy Hill, the movie is terribly dated but retains its fizzy charms, notably the undeniable chemistry of its two blue-eyed icons. Redford played the Sundance Kid, the mustachioed complement to Paul Newman’s Butch Cassidy. They’re a couple of train robbers who flee a posse, jump off a cliff together, hang out with a little lady (Katharine Ross) and eventually flee to Bolivia. The most famous moment in it comes at the end, when the film freezes on the two racing side-by-side into a hailstorm of bullets and certain death, a dewily immortalizing image.

In a way, the end of Butch Cassidy seems like an emblematic moment in Redford’s career. A few years earlier, the title characters in Arthur Penn’s galvanic Bonnie and Clyde had also died in a fusillade that played out to the gory end, leaving two grotesquely bloodied and mutilated corpses. Butch Cassidy, by contrast, presents a vision of eternal beauty that Redford himself seemed to incarnate almost mystically, even as the decades passed.

The film also suggested that somehow his characters could get out of any situation, even one as obviously dangerous as that in the great Three Days of the Condor (1975), a spy thriller co-starring Faye Dunaway and directed with great verve and style by Sydney Pollack. (You should watch it right now.)

As an actor, Redford was often best when appearing to do very little, when he had retreated into himself to watch the world. In Condor, he plays Turner, a shaggy-haired, unbuttoned CIA researcher who one afternoon returns from a lunch run only to find that all his co-workers have been murdered.

He’s soon on the run and almost as quickly embroiled with Dunaway’s Kathy, a civilian whom he takes hostage because he needs a place to hide. This still being a Hollywood movie, they fall for each other; not everything was new in that era of American film, including the sexual politics. Redford is perfect in the role, and while he gives the character an edge, he remains deeply sympathetic, trustworthy and, yes, unfailingly sexy.

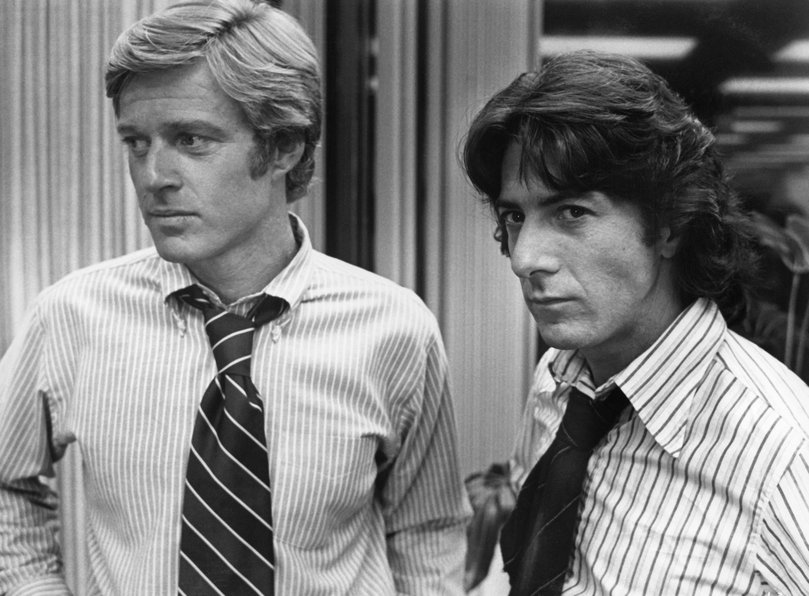

One of Redford’s gifts is that he was equally good at sharing the screen with men and women, which wasn’t always true of other 1970s male stars. He seems entirely comfortable playing against performers as different as Newman and Dustin Hoffman — he and Hoffman starred in another of the period’s exemplary films, Alan J. Pakula’s All the President’s Men (1976) — and, at times, Redford seemed wholly at ease deferring to them.

This talent or predilection of Redford’s brings to mind the dynamic you see between Brad Pitt, Redford’s most obvious screen heir, and George Clooney, in the “Ocean’s” movies.” Perhaps that sense of comfort comes from the confidence that is specific to beauty: Redford never had to fight for your attention.

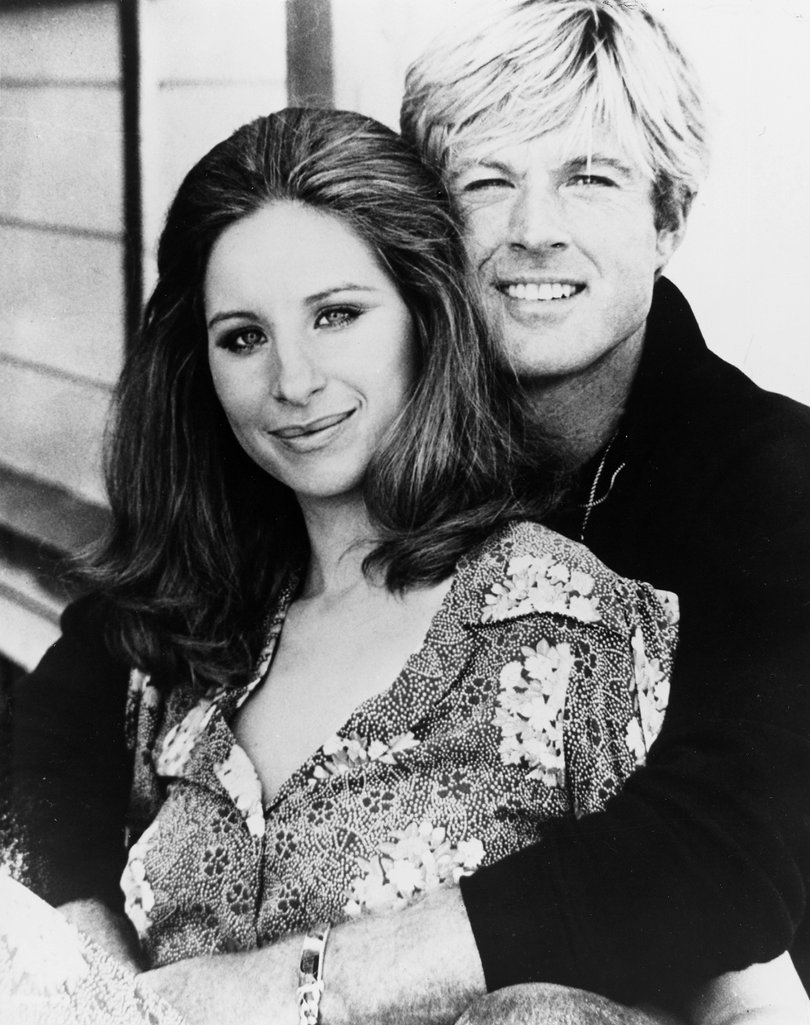

The 1970s are rightly commemorated as a high-water mark in American cinema, but it was also an era that wasn’t especially welcoming for women on-screen and certainly behind the camera. That said, one of the films that I adore without reservation is Pollack’s The Way We Were (1973).

A period romance that opens in the 1930s, it tracks the stormy, passionate and outwardly impossible love that starts between two college students, Barbra Streisand’s Katie, a fiery Jewish Marxist, and Redford’s Hubbell, an archetypal WASP who seems to have everything figured out. An entire dissertation on the female gaze could be written about how Katie-Streisand — yearningly, even hungrily — looks at Hubbell-Redford. Watching her watch him, I feel very seen.

In an important early interlude, the two are sitting in a creative-writing class when their professor begins reading aloud one of Hubbell’s stories. “In a way, he was like the country he lived in,” the professor says. “Everything came too easily to him, but at least he knew it.” The title of the story is, fittingly, The All-American Smile. The scene serves as a turning point because it shifts Katie’s thinking about him. The professor continues reading (“He worried he was a fraud”), Katie turns to look at Hubbell and the camera follows her gaze until it lands on him. He seems very uncomfortable with all the attention, and it’s clear that she isn’t just looking at his smile anymore; she at last sees the man.

Despite its glories, The Way We Were isn’t the kind of movie that comes immediately to mind when you think of New Hollywood. In truth, though Redford worked with some great directors and made some commensurately good, interesting films, he also made a great many middlebrow and forgettable films, including clunkers like The Great Gatsby (1974), a role that he seemed born to play. Yet despite his obvious talent, Redford often seemed most comfortable playing to type and playing it safe, and he couldn’t always rise above bad or indifferent direction. In contrast to some of his high-profile New Hollywood contemporaries, including Jack Nicholson, Redford wasn’t an actor who let his demons out to play.

After the New Hollywood faded, Redford’s roles generally grew less interesting, but his public persona became more intriguing. Amid his political activism, including his stated commitment to the environment, he made his feature directing debut with Ordinary People (1980), a melodrama about an uptight family coping in the aftermath of a death. It’s very sincere and features gauzy cinematography and a couple of fine performances, but it’s also overly neat, so of course it won best picture, despite competition from the likes of Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull and David Lynch’s The Elephant Man. Redford won best director, too, an award that is easiest to understand now, I think, as a gift from the Hollywood mainstream to one of its own.

“The danger of success is that it forces you into a mould,” Redford once said. “I prefer independence.” That makes his escape into the wilds of Utah all the more gratifying. Although he continued to star in films and also direct (Quiz Show from 1994 is a high point), Redford clearly didn’t want to be forced into a mould. So he ran away from Hollywood (well, kind of). He founded the Sundance Institute, made Hollywood come to him and fundamentally changed American cinema, often for better.

The history of those changes, and of both the institute and its famous festival, are complicated, yes, and sometimes vexed. Yet one of the things I love best about Redford — who was sometimes jokingly referred to as Ordinary Bob — is that he created a place where artists could cut loose, find community and make movies that he would never have starred in, much less directed himself. Unlike many in Hollywood, Redford sought something greater than himself, and he found it.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times