‘Take On Me’ has been stuck in our heads for 40 years. Here’s how it got there

The full story of how A-ha emerged from the Norwegian tundra with the ultimate ’80s pop song, and its unexpected afterlife.

Norway is a land of dramatic fjords, the midnight sun and the world’s finest goat cheese. It has never been known for its music. But 40 years ago, it produced a singular global pop hit whose grip on our ears has barely eased since.

What is it about Take On Me? If it’s not playing when you walk into the grocery store, you’ll probably hear it before checkout. Why is it the 1980s song that still reliably fills dance floors, enlivens seventh-inning stretches, helps to sell cars and breakfast cereal and rom-coms, challenges the bravest karaoke warriors and a cappella nerds, and continues to provide a formidable income for three men who could stroll through any world capital without being chased down for a selfie?

It would be unfair to call A-ha a one-hit wonder. Technically they had a few more hits after Take On Me - but nothing else even in the American Top 10, and nothing with anything like its staying power.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Where did this song, with its soaring falsetto and intoxicating synth melody, come from, and why do so many people, including many born well after 1985, know every word? (Or think they do …)

The story of a pop song is almost always the story of a band. Both A-ha and Take On Me may have seemed ephemeral back in 1985. But there was more going on beneath the surface, hidden hooks and elusive emotion within the song, conflicts and tensions within the trio - who, after decades of breakups and reunions, may never have the chance to perform it again.

The Oslo origins

Around 1974, when Magne Furuholmen was 11 or 12, he noticed a slightly older kid in his Oslo suburb standing on a balcony. He was drumming, but he didn’t actually have drums, only a homemade kit made of cardboard.

Magne talked to him that day.

“You know, I have a guitar, electric guitar and amp,” he told his new friend, Pal Gamst, then 12.

Magne was an outgoing boy shadowed by a terrible tragedy. When he was 6, his jazz-trumpeter father, Kare, died in a small plane crash. Pal - who would eventually take his mother’s surname and become known after his marriage as Paul Waaktaar-Savoy - was the shy, introverted son of a pharmacist and phone company worker, who connected with music in ways he couldn’t quite do with his peers.

The duo made their debut on May 17, Norwegian Independence Day, setting up on the lawn at their housing complex.

“We just made a lot of racket, and the police came and the neighbours were like, ‘what the f...’s going on? Nobody told us about this’,” recalled Magne.

At 14, Magne dreams up a bouncy keyboard riff. Paul snickers that it sounds like a commercial. “Well yeah,” Magne recalls telling him, “but it’s catchy though, right?”

With the exception of a few prog rockers, Norway was a kind of tundra for popular music and Western culture in general. The state radio station played a single hour of rock each day. McDonald’s didn’t arrive until 1983. As the two friends hit their teenage years, they purchased rail passes and rambled around Europe, tracking down LPs.

“We were really heavy into Deep Purple, Bowie as well, and super into Hendrix,” Paul told The Washington Post. “Nobody listened to Hendrix back then.”

“I bought a Doors record,” Magne explained. “Paul hadn’t heard of them, and then we played it, and that became a huge influence on our direction.”

The Doors record was Waiting for the Sun, known for its single Hello, I Love You. And indeed, Magne and Paul’s first professional collaboration, a four-piece band called Bridges that they launched in 1978, was drenched in the baroque ambiance of the LA rock band. On Bridges’s only released album (Fakkeltog, Norwegian for a parade of torches), Paul - who had nudged Magne to trade the guitar for Ray Manzarek-inflected keyboards - took on lead vocals in a deep, moody voice reminiscent of Jim Morrison.

But Bridges wouldn’t last.

“Those two guys, they were different,” said Bridges bassist Viggo Bondi, who eventually became an attorney. “It was all about music, their ambitions, which I think was a little bit funny, actually, because technically they were not very good musicians at the time.”

In 1981, Paul writes the verses to a new song and plays them for Magne, who remembers his old keyboard riff. They bring it into the mix and Paul writes lyrics for a song that Bridges records as Miss Eerie. It’s an odd hybrid of garage rock and ska, but Paul thinks it’s too slick - like a Juicy Fruit gum jingle, he jokes - and they never release it.

In 1982, Paul and Magne realized they had a choice. They had watched one of their favourite local bands, punk rockers Kjott (which translates as “meat”), go nowhere. To make it, they needed to move. Instead of going to college, they relocated to a cheap flat in London.

“In Norway we knew there were 4 million people looking at these other cool bands that we liked that couldn’t sell more than 500 records,” Paul said. “I knew we would just put in so much effort and get nowhere.”

They were eventually joined in London by Morten Harket, a vocalist from the Oslo suburbs, whom Bridges had rejected earlier because the band already had a singer. As a child, Morten had fallen in love with butterflies and insects; after high school, he briefly studied theology at an Oslo seminary. But once he heard Uriah Heep’s prog-rock classic Wonderworld for the first time, he realized his destiny was music.

Now down to two members, the evolving combo needed a singer after all. Morten finished a planned trip to Greece and joined them in London, where they formed a new trio.

They called themselves A-ha - inspired by a snippet of lyrics in Paul’s notebook - and were signed by Warner Bros UK.

Paul shows his new bandmate a passage he has been tinkering with on Lesson One, a song that emerged out of Miss Eerie. His idea for a chorus: an ascending line of notes that, to Morten’s ear, sounds too much like the monumental horn-blast opening of Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra. The singer suggests a slightly different rising melody.

“Yeah,” Paul agrees, “now I know what to do.”

At least that’s how Morten would tell the story later.

Synth-pop and an aesthetic Orbison

The three quickly adapted to the ascendance of synth pop - the machine-made beats and electronic grooves of hot new bands like the Human League, New Order, Duran Duran and Depeche Mode. In 1984, when it was time to record an album for Warner Bros., A-ha resurrected the hook-filled tune that band members had been collectively chipping away at for the better part of a decade - the song first known as Miss Eerie and now thoroughly made over, with new chorus and lyrics, into a synth-friendly demo called Take On Me”that delighted label execs.

Producer Tony Mansfield eagerly deployed his Fairlight CMI synthesizer, which he had used two years earlier to turn a nearly forgotten Burt Bacharach song, Always Something There to Remind Me, into an American Billboard Top 10 hit for British duo Naked Eyes.

Still, something didn’t quite work. Take On Me tanked upon its European release in October 1984. It never made it to the States that year.

Plenty of new bands fail to connect. Usually, they are quickly dropped. But Warner Bros wasn’t ready to let go. And this had a lot to do with Morten’s particular star quality.

His vocal range was amazing, as his bandmates testified. “Because it’s like it’s a falsetto,” Magne told The Post. “But then the top end is like a mix between the chest voice and a falsetto. He has a lot of power up there; that’s what blows people away. I can get up there, but his oomph is what just kind of knocks you sideways.”

Morten reminded Jeff Ayeroff of Roy Orbison - the rockabilly giant with a three-octave range and gift for vocalizing heartbreak - but with one key difference: Morten was devastatingly handsome, dark-haired with chiselled features and twinkling eyes.

“This guy had an operatic voice, but he was perfect-looking,” recalled Ayeroff, at the time a top creative executive at Warner Bros. “If Roy had looked like Elvis, he would have been twice as big as Elvis.”

Colleagues at the label respected Ayeroff’s eye for talent. He had helped break Madonna and revive the careers of Steve Winwood and Paul Simon. He knew the power of MTV. His artful campaign for the Police’s Synchronicity, particularly its music videos, had helped fuel that band’s rise into pop-world dominance.

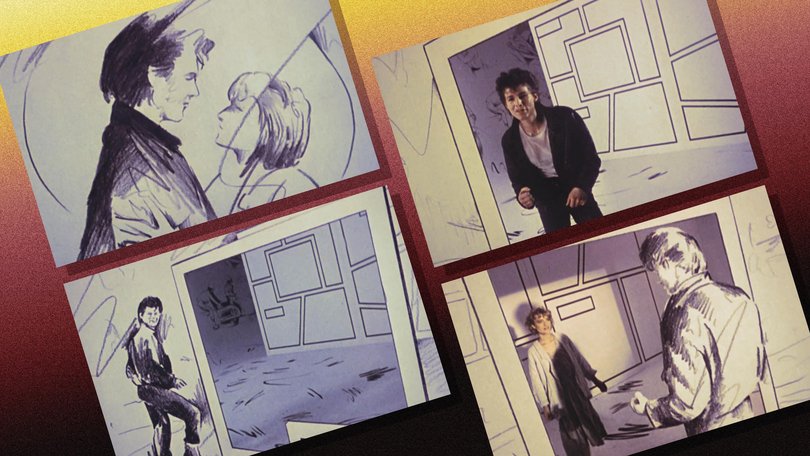

A-ha’s first video attempt had looked like so much else on MTV - three guys in new-wave haircuts performing on a monochrome set, interspersed with quick cuts of a near-faceless Flashdancer. Ayeroff thought back to a short 1981 animated film made by a college student with no experience in music videos. Michael Patterson’s Commuter used impressionistic pencil drawings to evoke the flickering cartoons of the 1930s and ’40s. Ayeroff had signed Patterson and his creative partner and wife Candace Reckinger to a holding deal with Warner Bros. Now, he brought them to headquarters to talk A-ha.

He wanted their ideas in a week.

“Is that too fast?”

“We can do it,” Patterson said.

The perfect production and a comic comes to life

Meanwhile, Andy Wickham, a British executive at Warner Bros., who had signed Joni Mitchell and Van Morrison in the 1960s, still heard missed opportunities in A-ha’s flop single. He went to Alan Tarney, a producer who had turned down Warner Bros.’ effort to hire him for the initial recording. Nothing against A-ha or the song - he simply disliked working with bands. (“It’s hard to control them,” he told The Post. “They all have opinions and, in the end, it just becomes a bit chaotic.”)

This time, he made an exception. And A-ha proved easy to work with.

The Norwegians were broke by this point and owned no synthesizers. So they used the producer’s equipment - his Roland Juno-60, his LinnDrum machine. They fed Magne’s keyboard lines into Tarney’s computer, where he multitracked them into a wall of synth, creating the distinctive steel drum sound. Tarney also recorded a lengthened ending of “Take On Me,” adding a repeat of the chorus rather than a quick drop as on the Mansfield original.

The Tarney version was clean but lush, packed with more than a half dozen different keyboard parts, an acoustic guitar, percussion, harmonies and a stunningly beautiful performance by Morten, whose piercing vocals had been blurred by an echo effect during the first recording.

“It just sounded like them, and I could see what it was that the record company wanted,” Tarney told The Post. “It was charming. And they were just so happy to get into the studio and make a record. ‘Take On Me’ was made in a day.”

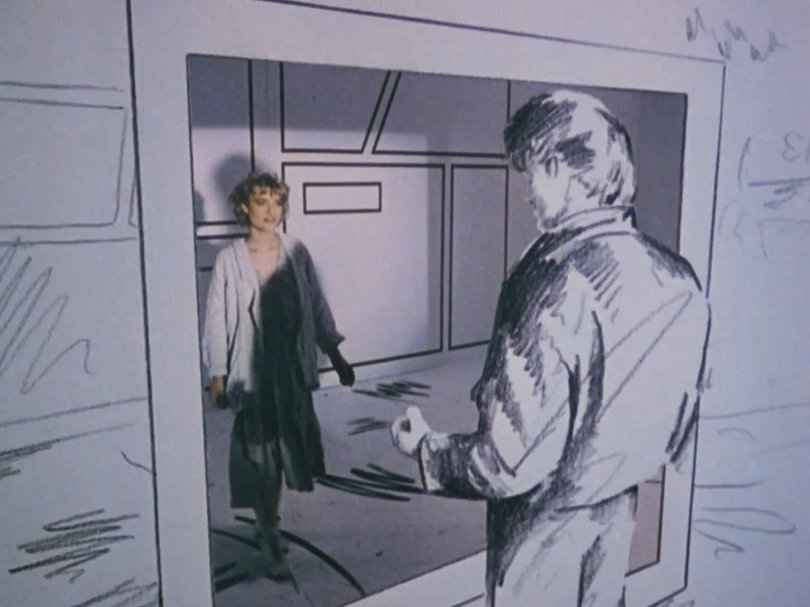

Warner Bros. was willing to gamble on a pair of first-time video makers, but it needed a veteran running the show. Steve Barron, who had made Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean, got the job to direct Take On Me. They found a cafe near London to use as the set and hired wide-eyed dancer Bunty Bailey to play Morten’s love interest.

The idea was a comic book come to life. Ayeroff’s vision was influenced by the Fleischer brothers, whose prewar black-and-white cartoons, including Popeye and Betty Boop, had an artful scratch-pad rawness; and the 1985 Woody Allen fantasy The Purple Rose of Cairo, in which film hero Jeff Daniels steps off the screen to romance theatregoer Mia Farrow and pull her into his cinematic world.

The video looked like nothing else on MTV. A girl, alone at a diner, reads a comic book about a handsome motorcycle racer, who suddenly becomes animated (Patterson used a striking and painstaking frame-by-frame technique called rotoscoping) and pulls her into the pages. A window within this fantastical space allows her to glimpse him as a flesh-and-blood person, and him to see her as his graphite-sketched counterpart.

Released in the United States in spring 1985, Take On Me stormed the charts - powered by its heavy rotation on MTV - and hit No. 1 on October 19. It was a similar trajectory in Britain, Norway, Canada, Australia, all across Europe. It was certified gold in Japan, platinum in Brazil.

‘A massive monster on the loose’

Then, the old, familiar story of so many bands before and since.

They had never toured before. But suddenly, with millions of records sold, A-ha travelled the world, playing the US, Australia and finally England, including three consecutive nights at London’s Royal Albert Hall. Producers signed them to do the theme for a new James Bond movie. Morten, the heartthrob with blue eyes and a mischievous smile, became a pinup star, gracing the covers of magazines such as Blue Jeans, Tutti Frutti and Starlet.

“We didn’t know what we got ourselves into,” Morten recalled. “And no one knows until it hits you, from within, from behind, from head on. It’s a massive monster that’s on the loose. And it’s impossible to explain or convey to anyone who hasn’t experienced that level of attention.”

As time passed, A-ha lost relevance in America, with their 1986 second album, Scoundrel Days, rising no higher than 74 on the US charts and their 1988 follow-up, Stay on These Roads, failing to crack the top 100. They have remained popular in Europe: True North, their most recent album, rose to No. 12 in Britain just three years ago.

The problems were the same ones that hampered the Police, Talking Heads, Oasis, N.W.A., the Beatles. All about money, credit, control. Morten and Magne felt that Paul was selfish about all three, a tyrant in the studio who wasn’t nearly as responsible for their success as he claimed. He started to find them difficult and manipulative as co-workers.

Morten today maintains that the 16.6 percent he says he receives of the publishing total on Take On Me - with Paul and Magne splitting the other 83.4 percent - is less than he deserves.

You hear that first rising passage at the start of the chorus? The part where Paul was originally going for more of a “Zarathustra” thing? Morten is the one who fixed it.

“That note in between there is what sets the whole thing off,” he said, after humming the line to The Post in Oslo this fall. “And that came from me.”

Paul downplays the contribution. Morten helped on the lyric and changed that note on the chorus, but he did not otherwise contribute to the melody. He told The Post that, to make Morten happy, he agreed to split future song revenue evenly - as long as Morten, who frequently refused to work with him, agreed to sing 20 new songs over five years that Paul came up with. That voice, he said, is unlike any other. Paul alleges that Magne talked Morten out of the agreement. Magne calls Paul’s description a “paranoid delusion” and that he had nothing to do with whatever deal was proposed.

Whatever the reality, the split on their biggest hit (Take On Me has been streamed more than 2.5 billion times on Spotify to date) remains a barrier.

An icy impasse

Earlier this year, Morten, now 66, revealed a not-so-minor complication for the future of A-ha. He had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, a progressive illness that in some cases takes a particular toll on one’s voice.

He isn’t sure when he’ll be able to perform again, as he adjusts to his medication. “I haven’t felt like singing,” he says. The disease has also taxed his stamina.

Now, a machine on his waist delivers dopamine supplements. A clicker controls the impulses delivered to electrodes implanted in his brain. He tires easily and can’t always predict when he’ll feel good, or when he’ll feel muddled and lethargic. But over the past month, he has seen some improvement for the first time since his diagnosis. Now, he can imagine singing again. He shares some demos on his phone.

But would he sing them with A-ha?

“I don’t have the drive for the band as a unit anymore,” he said. “I’ve served my time. And I won’t be doing it unless certain things come into place. … Some level of mutual respect for each other’s roles and place in the band.”

He has even suggested to Magne, with whom he recently hung out, that they go it alone. The keyboardist rejected the idea.

“It would be an injustice to history to do it,” Magne, now 63, told The Post. “For good or bad, the three of us are what made A-ha … our great moments, our s...ty moments, friendships, our falling-outs.”

But he notes that between Morten’s health and the assorted personality conflicts - the three haven’t been in the same room since a concert in 2022 - the band lacks a forum to celebrate the anniversary of its greatest hit. Magne remains busy with his own projects: An accomplished visual artist, he runs a studio, collaborates with other musicians (his band, Apparatjik, includes Coldplay bassist Guy Berryman) and continues to record music at home.

“Morten’s condition is obviously one that has been leading to lack of plans,” he said. “But it’s also the general dynamic in the group that has made it really difficult to sort of collectively say, look, we need to just some way, some classy way, acknowledge that it’s been 40 years since we started.”

The rumour, in Norway, is that they’re always arguing. If only that were true.

“Because that would mean that they would talk,” said Harald Wiik, the band’s former manager, who remains a consultant and in contact with each individually. “It’s quiet, like an ice front. Nobody wants to make the first move.”

The hidden meaning

In 2017, A-ha performed a concert, filmed for an “MTV Unplugged” special, on the Norwegian island of Giske. Even with the open sea behind them and guest appearances by cult favourites such as Alison Moyet and Ian McCulloch, the real star was a pop hit they had to record twice before they got it right.

Take On Me was rearranged, slowed down, with a wash of Coldplay-meets-Radiohead. Morten delivered a heart-wrenching interpretation, with a poignant twist at the chorus: After rising his falsetto at “I’ll be gone” as usual, he dropped lower to deliver “in a day or two.”

Oh. Is that what that lyric is?

In the 1980s, you couldn’t just look this stuff up on the internet. An online compendium of misheard lyrics suggests that this passage may have been the most elusive part of Take On Me for fans. (Typical guesses ran along the lines of I’ll be gone, do de doo doo, doooooooooo.)

The melancholy line, so frequently lost in Morten’s glorious soar, is suddenly laid bare, and it’s an unexpected emotional wallop. Audience members mouth the words. One woman captured by the camera tears up.

Which leads to the great question behind the song. What does it mean to “take on me”?

Paul, now 64, who wrote it, brushes off the significance.

“We were in England trying to become pop stars, trying to get a recording deal, trying to take on the world … so it was just a play on that,” he said. “Take me on and deal with me, or check out what we have to offer. It really was just kind of as simple as that.”

His wife, Lauren, believes it’s not that simple. She senses a deeper, emotional connection to the lonely, awkward, sweet Norwegian boy who love-bombed the American girl he met in a club in 1983.

“He would write me three letters a day,” she laughed. “He would send me cassettes. Here’s a song I wrote for you. Here’s another song I wrote for you. Here’s another letter. Here’s a drawing of you. Here’s some Norwegian chocolate that I just sent from Norway that got melted. I mean, it was an onslaught.”

“When I hear ‘take on me’ and ‘take me on,’ I think of Paul,” she said.