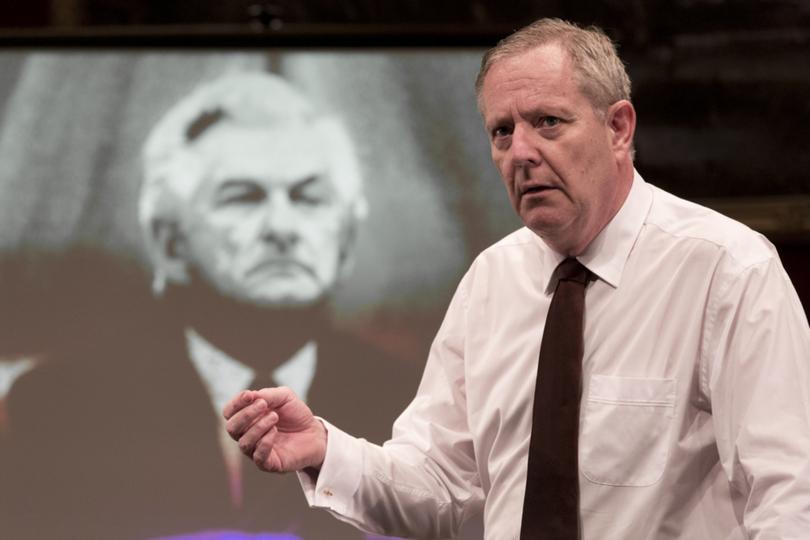

The Gospel According to Paul: Jonathan Biggins on why former PM is still so fascinating

One-man comic mindful of not being bamboozled by the force of the former PM’s charisma.

When Jonathan Biggins opened his one-man comedy show, The Gospel According to Paul, in 2019, there was a stream of political luminaries and Hawke-Keating era cabinet ministers who let their curiosity get the better of them.

But it wasn’t the likes of Gareth Evans or John Dawkins sitting in the audience that made Biggins nervous. It wasn’t even the man himself, Keating.

“The scary one was when I was in the foyer after the show and I saw Annita (van Iersel, Keating’s wife from 1975 to 1998) approaching with one of her daughters, and I thought, ‘Oh’,” Biggins told The Nightly.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“And she said, ‘Thank you, I didn’t really want to come and see it everyone said I should and I’m glad I did’. I make mention of her and there are a few moments, because he’s a very private person, where the shield drops and you get a vulnerable man, and they’re all related to family.”

In 90 minutes, Biggins captures the larger-than-life personality, legacy, towering intellect and, yes, even the emotional side of Keating, and he’s bringing back The Gospel According to Paul for an encore season including at the Sydney Opera House.

“He’s a character that lends himself very well to the theatre, because he’s so theatrical himself,” Biggins said. “That’s his whole schtick, throw the switch to vaudeville.”

He’s played a version of Keating since his days writing and performing for the Wharf Revue, when the character was much more based in satire, but Gospel is more of an “unauthorised theatrical biography”.

Biggins is mounting the production for the first time since Labor reclaimed the Federal Government, but the show won’t be undergoing wholesale change. Just a few tweaks to reflect Albanese’s prime ministership, and Keating’s war-of-words with foreign minister Penny Wong over China.

“I’m going to have to make some reference to the so-called sprays against Penny Wong, which, when you read then, are pretty mild,” Biggins said. “I mean, they’re not really sprays. And I think Penny Wong can look after herself, she’s no shrinking violet.

“That sort of argy-bargy used to go on all the time in the ALP, they’re much more tightly controlled now.”

For Biggins, Keating is part of a bygone era of Australian politics, when Labor had conflict between its right and left, instead of its centrist discipline, when Federal oppositions were constructive instead of destructive, and when governments’ ambitions weren’t limited by a desperate cling to power.

He argued there hasn’t been a leader with as much dynamism as Keating since Keating.

“We certainly haven’t had anyone who did the amount of reform that the Hawke and Keating governments did over their 13 years in power,” he said. “It was a different time. Politicians now spend so much time trying to hold on to the hourly news cycle. It’s relentless, one crisis lurching to another because things happen so quickly

“That sort of broad-scale policy that Keating and Hawke did was massive. They weren’t tinkering at the edges. They were fundamental, and I don’t think anyone is given the time or space to do that now.”

Biggins has met Keating several times over the years, starting with his time doing the Wharf Revue, and he’s mindful of not being bamboozled by the force of the former PM’s charisma. He emphasised the unauthorised nature of the production means he has a bit of creative licence. And he didn’t want it to be fawning.

“But it’s very difficult when you are playing someone who is not open to self-criticism, to introduce that into a narrative when he’s the only person there. So you try to let some of the hubris speak for itself.

“It’s difficult too because he’s pretty fond of his legacy and you have to show that famous arrogance. But the thing about arrogance like that – or when people call it arrogance – is that he actually earns it. You know that most of the time he’s right. And people get very annoyed with people who are usually right.”

Keating left school when he was 14 years old, was an autodidact, managed a rock band, got his pilot’s licence, a bus licence and is so adept at collecting antiques that even the Smithsonian wants to buy pieces he owns. He was famed for his cutting wit.

All that and more is why Biggins believed there’s still a fascination with Keating, even if he is now sometimes dismissed as a “grumpy old man” – “It’s kind of ageist... but they’re not dismissing the arguments”.

It’s the strength of his personality, his convictions and his record that draws audiences to The Gospel According to Paul Keating, Biggins said, even if you don’t like him.

“Love him or hate him, everyone kind of respects him. So, it doesn’t matter where you play (the show) in the country.”

“You could be in a strong Liberal electorate and they still came along to see it because they were not only fascinated by him but they respected him for what he did, or they saw he was a genuine leader who didn’t try to be popular but recognised there were certain things that had to be done.

“This has been lacking in recent years, shall we say?

“That’s the fascination for people. They want that back, they want that sort of figure to come again. And they don’t realise, in a funny sort of way, they’re preventing it. We always get the governments we deserve and the governments we enable.”

The Gospel According to Paul opens at the Sydney Opera House on June 4