The ‘Kryptos’ code at the CIA headquarters has gone unsolved for 35 years. Now it’s up for sale

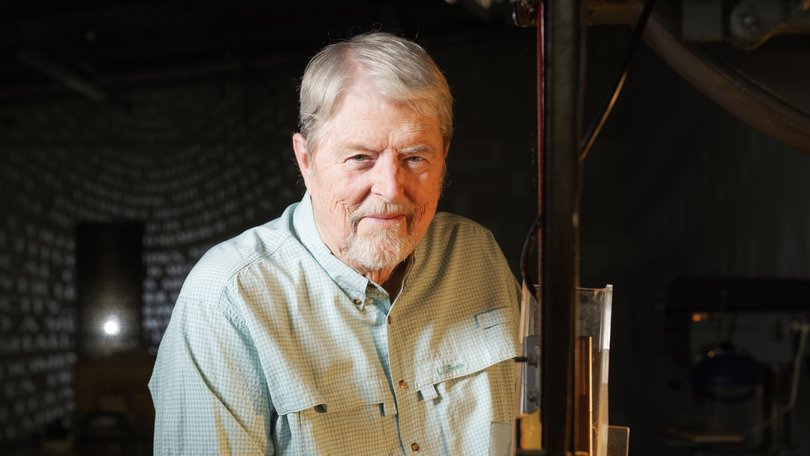

When artist Jim Sanborn talks about ‘Kryptos’, his sculpture at the CIA headquarters, and the famously unsolved secret code engraved in its copper panels, he sounds as if he’s talking about espionage, not art.

The piece has “destroyed marriages,” he claims. It’s driven “unwanted guests” to his doorstep.

Some aspiring code crackers have even “threatened my life,” Sanborn says, prompting the artist to outfit his home with panic buttons, motion sensors and cameras.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.But after 35 years guarding the work’s secrets and dealing with the drama that comes with it, Sanborn is ready to hand over the code.

In November, he plans to auction off the coveted solution to the final passage, known as K4, at a sale coinciding with his 80th birthday.

“I could keel over at any minute and I’d rest easier if I knew that things were in control somehow,” he said.

In a letter to fans, Sanborn wrote that the decision “has not been an easy one” and acknowledged “many in the Kryptos community will find it upsetting,” but, “I no longer have the physical, mental or financial resources” to maintain the 97 character code and continue his other projects.

He writes in the letter that he hopes the buyer keeps the code a secret, dropping a rare hint to his followers.

“If they don’t then (CLUE) what’s the point?” he writes. “Power resides with a secret not without it.”

The sale, which will be run by Boston-based RR Auction on November 20 and whose proceeds will go in part to programs to help the disabled, includes the original, handwritten plain text of the K4 code as well as other documents associated with the work.

The secret will be transferred via armoured vehicle, the auction house said. It is expected to sell for between $300,000 and $500,000 ($AU$460,000 to $770,000) according to Bobby Livingston of RR Auction, though he said he wouldn’t be surprised if it fetched more.

“The way cryptocurrency has really taken off, there’s a whole world out there that this appeals to,” he said.

Indeed, since Sanborn completed the sculpture in 1990, expecting its messages would be decrypted in just a couple of years, the piece has attracted a borderline fanatical cult following.

It’s forged communities of decoders, been a subject of academic research, graced algebra textbooks and appeared in film, books and television, sparking a level of interest that most artists could only dream of receiving.

But managing the piece has also turned into something of a job for Sanborn, who is based on an island in Chesapeake Bay.

He has fielded tens of thousands of messages from would-be code breakers, which he says have surged amid “meaningless” AI-generated decryptions, and even instated a $50 fee for guesses to try to slow the submissions.

These days, he is working on an AI-powered phone line that will respond to callers’ potential solutions, possibly using his voice.

And that’s just the bureaucratic side.

“There can be an addiction in some people,” he said. “I try to talk them out of it as best I can . . . Sometimes it ends well and sometimes it ends very badly.”

With Kryptos’s final passage remaining unsolved, the piece could be understood as a kind of monument to secrecy, or a performance piece, starring Sanborn himself.

In a news release about the auction, he noted he now clearly understands “the burden of keeping secrets.”

Peter Krapp, a film and media studies professor who studies the culture of secret communications and cryptological history at the University of California at Irvine, lamented the idea of privatising the solution through an auction, calling it “both sad and logical.”

The knowledge that went into the piece “ought to be shared, not withheld — especially considering that other people, not just Sanborn, contributed to the making of Kryptos,” he wrote in an email.

The CIA commissioned Kryptos in the ’80s as a part of an art program that Sanborn says aimed to “soften” the agency’s image, which had been damaged by revelations of Cold War abuses and a critical Senate investigation.

Krapp says the work has become a “publicity coup” for the CIA, the public image of which has become tied to the artwork.

The piece has fascinated all kinds of people, who seem to have little in common beyond an interest in cryptography, Krapp says.

“Some see it as a battle of wits, some as a test for their software, some as a hobby that keeps them engaged with cryptology after their active career at the bleeding edge has come to an end.”

Krapp said he is amazed at how Sanborn is capable of keeping these enthusiasts’ “interest in his work burning bright, but without revealing anything that would ruin their search.”

Hardly a cryptographer himself, Sanborn has been an unlikely steward of Kryptos from the beginning, noting he was tutored in maths every summer “to be able to get a D”.

Still, he had a passion for spy novels and when planning a piece for the Langley headquarters, he wanted to create a work that could “hold its own in that environment, both conceptually and physically,” he said.

The physical work required “a huge amount of blood and treasure” that nearly bankrupted him, Sanborn said.

He recalled hauling “many, many tons” of stone into the CIA courtyard through standard sliding doors on nights and weekends and spending two and a half years going through nine different assistants to carve more than 1700 characters into the surface of the work.

The final piece consists of petrified wood supporting a wave-shaped copper screen, which stretches around a pool of water, a peaceful design that is meant to stir contemplation.

For the conceptual side, Sanborn teamed up with Ed Scheidt, then the retiring chairman of the CIA’s Cryptographic Center, who spent months designing systems for encryption that Sanborn then adapted to hide his messages.

The first two portions of the piece are considered easy enough for almost anyone who has studied basic cryptography to decode.

K1 translates to: “Between subtle shading and the absence of light lies the nuance of iqlusion,” an intentional misspelling.

The second passage, which is longer, describes buried information and suggests “WW” — believed to be William H. Webster, the recently deceased former director of the CIA — knew where it was.

The third portion, considered much more advanced, is a passage from the diary of British archaeologist Howard Carter that describes opening up King Tut’s tomb.

The fourth, of course, has yet to be cracked and it’s not the end.

“K5 is going to be somewhat inscrutable as well,” Sanborn said cryptically in the interview. Asked if he’s referring to more characters that will need to be decoded, he replied, “Well, I can’t say now, can I?”

Klaus Schmeh, an expert on the history of encryption, calls the progressing difficulty of the various portions a “clever strategy” to drive interest in the work.

“Both the solved parts and the remaining mystery make this cryptogram attractive for puzzlers and the media,” he wrote in an email.

He said he’d like to see it finally solved, so “perhaps, other mysteries of this kind would then receive more attention.”

Sanborn has gone back and forth on whether he’s rooting for his code to fall. He mused to CNN in 2020 that he “wouldn’t be distraught if it ended tomorrow.”

But, in a conversation about the auction this week, he appeared more sentimental.

“I’d rather it not, only because I’m an artist and every artist is trained to make artwork which has lasting presence and lasting value,” he said, noting you can look at a Van Gogh “a thousand times and see it in a new way.”

And as long as Kryptos remains uncracked, there’s certainly something to look at.

Originally published as The ‘Kryptos’ code has gone unsolved for 35 years. Now it’s up for sale.