Top 50 artworks to see in Australia before you die, part five

Welcome to our unfolding, unranked list of the best 50 artworks in Australian museums and galleries, taking you on a chronologically arranged tour of beauty.

You can find out more about how these works were chosen in the full introduction, but simply put: this list has a single author and therefore is highly subjective but has been put together with consideration of what each gallery or museum considers to be its most important and its most popular works.

Almost all these works are on display at the time of publication, meaning you can go and find them in the real world.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.If you want to find out what art is in any given gallery, the major ones all have searchable online databases. Most of them have pretty reliable filters that allow you to see what’s currently on display. All the galleries featured are free, except Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art, which is privately owned.

Happy art-hunting!

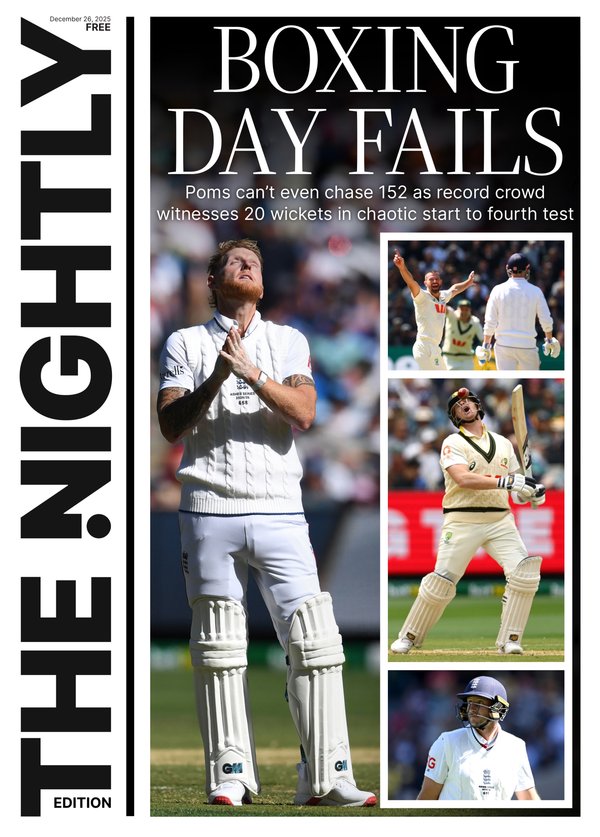

Requiem for Vermin (2019)

Chris Townend, a Hobart-based sound artist (and head honcho at MONA’s recording studio), designed Requiem for Vermin for the striking subterranean sandstone tunnel where it resides.

Walk slowly to fully appreciate the 218-channel design, played through 230 speakers interacting with 16 movement sensors in the ceiling.

The sound is immense, dense, like a turbulent ocean. You’d never guess it was the result of harps being played in strange ways with unusual materials (including grass and fishing reels).

Townend has purposefully designed Requiem for aural hallucination: as your brain seeks to navigate the complex soundscape, you hear instruments and sounds that are not there. It’s magnificent.

On permanent display at the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), Nipuluna/Hobart.

![Boekan Katjoeng [Not the 'katjoeng' (The Savage)] (2019) by Jumaadi © Jumaadi. Supplied: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Photograph: Tim Connolly.](https://images.thenightly.com.au/publication/C-14864407/f879cab157535983d03ebbb28f4fdca3fcd2ea70.jpg?imwidth=810)

Indonesian Australian artist Jumaadi has an instantly recognisable aesthetic all his own, drawing on an eclectic mix of traditional Javanese and Balinese, European and folk art.

These four paintings reference the story of a group of Javanese workers arrested by the Dutch authorities during the Indonesian independence uprising of 1926-27 and exiled to prison camps in West Papua.

In 1943, with the Japanese army advancing, the remaining internees were transferred to a camp in Cowra, NSW. Jumaadi’s magical-realist imagery, inspired by poems by the detainees, elevates a chapter of recent history and these people’s experiences to something mythic and epic.

On display until August 11 as part of MCA Collection: Artists in Focus at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), Warrane/Sydney.

Baratjala (2019)

This expressive painting is inspired by the cyclonic weather and lightning strikes at Baratjala, an important estate for the Madarrpa clan of artist Ms N. Marawili.

An aesthetic innovator, Marawili developed her own, non-sacred visual language to depict Baratjala’s rocks, water and lightning.

She was also among several Yolnu artists at Yirrkala who received permission to use non-traditional materials, on the basis that rubbish (such as old road signs) is now - like bark and ochre - technically “from the land”.

This allowed her to mix magenta ink from spent printer cartridges into the white ochre she used to startling, seductive effect.

On display at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Naarm/Melbourne.

Carving Country (2019-21)

This massive linocut by veteran Brian Robinson (Maluyligal, Wuthathi and Dayak people) and emerging artist Tamika Grant-Iramu conjures a jacaranda with sprawling branches. Robinson took the left side (decorating the negative space) and Grant-Iramu the right (focusing on the trunk and branches), though there is some leakage into each other’s space: intricately carved blossoms by her; traditional “minaral” (the patterns or decorations of Zenadth Kes/Torres Strait Islands) by him.

Robinson’s imagery is a Where’s Wally of pop cultural icons, from Alice in Wonderland to Pac-Man and Papa Smurf. This, and the bleeding between positive and negative space, give a psychedelic edge to this work’s beauty.

On display until August 18 in Seeds and Sovereignty at Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, Meeanjin/Brisbane.

Targets (2020-21)

For this epic, 34m long artwork, which wraps around AGWA’s Rooftop terrace, artist Christopher Pease (Minang/Wardandi/Bibbulmun people) remixed a picturesque, European-style depiction of Derbarl Yerrigan (Swan River) from 1827, and expanded it into a panoramic vista, based on his research and knowledge of the area.

Signs of Noongar presence and the impact of colonisation have been added (an empty shelter; a colony of white rabbits), and the scene is overlaid with Pease’s trademark sets of concentric circles in red and grey - like targets, but also waterholes or campfire sites.

At night, backlighting transforms the panorama into an illuminated display of Noongar ceremonial markings.

On permanent display at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA), Boorloo/Perth.

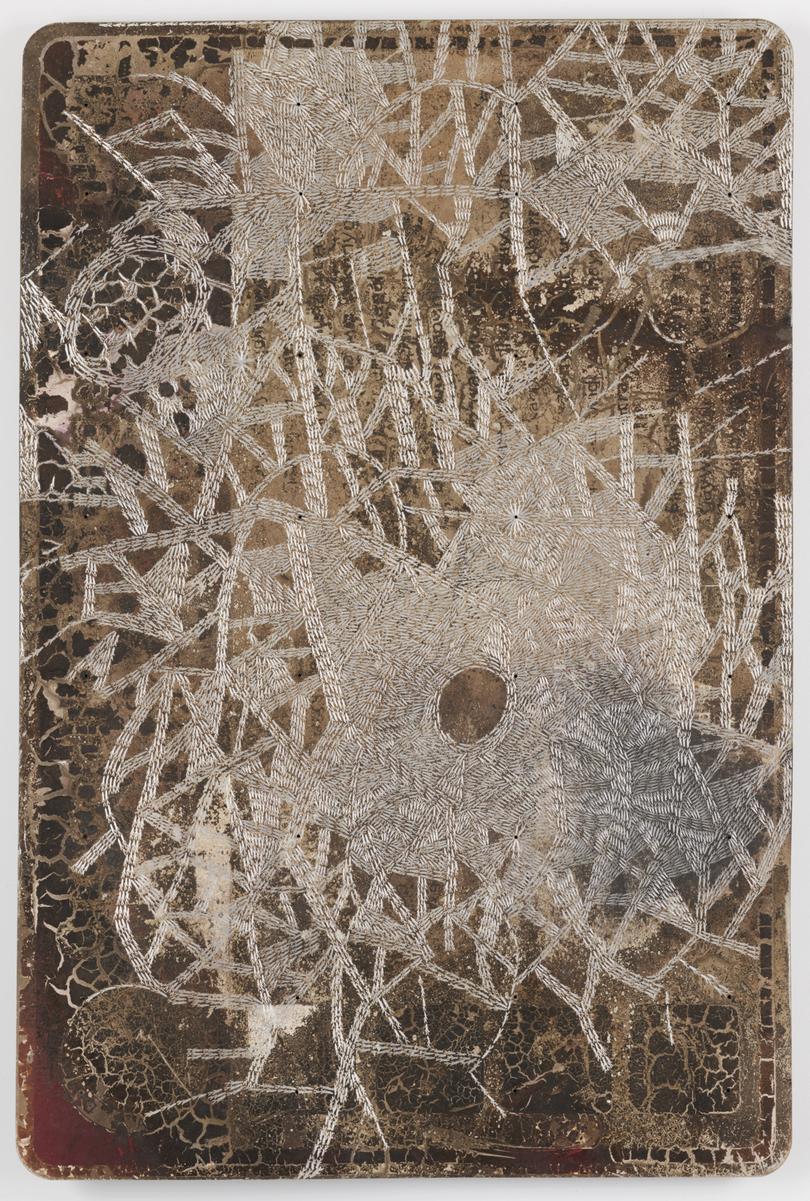

Wawurritjpal (2021)

Schools of tiny sea mullet have been etched into the metal of this work in such a way that as you walk past, different strands of fish, and overall patterns, gleam brighter than others.

The late, acclaimed Yolŋu senior artist and leader W. Wanambi is known for his paintings of wawurritjpal (sea mullet) on bark and larrakitj (hollow memorial poles), and in recent years, on discarded road signs from the country around Yirrkala, north-east Arnhem Land, where he lived and worked.

He was among a number of Yolŋu artists who transferred their designs onto found metal, including frontrunner Gunybi Ganambarr.

On display in the Yiribana gallery, Naala Badu, Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Warrane/Sydney.

Belonging (2021-22)

Grace Lillian Lee calls these statuesque woven sculptures “wearable objects”.

They look a bit like body armour, and even though they’re not being worn here, you can almost feel the presence within each one.

The “grasshopper” weaving technique used here was passed to Lee by senior Erub artist Ken Thaiday, celebrated for his elaborate dance headdresses (dhari). Lee trained in fashion design, and her jewellery and millinery are highly sought after.

With Belonging she combines her own aesthetic with elements of the traditional dhari design. The red piece in the centre represents Lee and her Zenadth Kes/Torres Strait Islander ancestry and connections.

On display in the Yiribana gallery, Naala Badu, Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Warrane/Sydney.

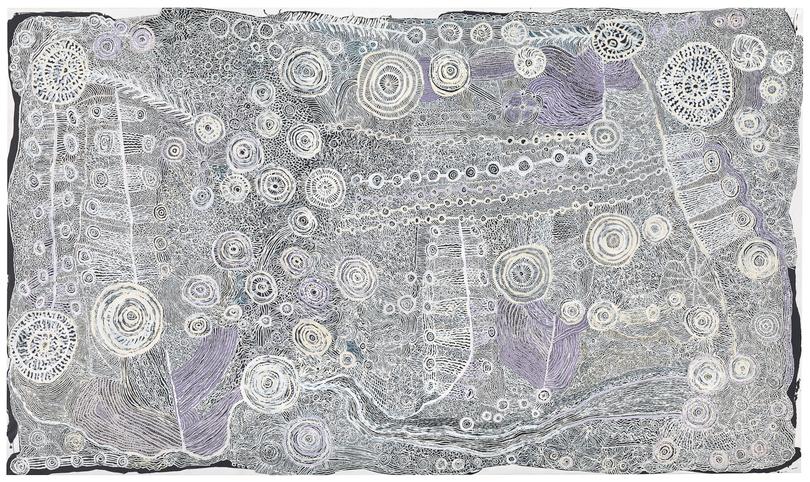

Betty Muffler’s paintings stop you in your tracks and transfix you with their shimmering complexity.

The senior Pitjantjatjara/Yankunyjatjara woman and ngangkari (traditional healer) only took up painting within the last decade, and found acclaim in 2017 with her ongoing Ngangkari Ngura series, depicting her tjukurpa (ancestral creation stories) and Country.

These paintings show waterholes, waterways and sites of healing from the aerial perspective of Walawuru/the eagle (one of her key tjukurpa), but her use of white in different opacities on a black background, and her patterning, has also been described as producing an almost atmospheric effect.

In the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Naarm/Melbourne

Groundloop (2022)

Aotearoa/New Zealand Maori artist Lisa Reihana (Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Hine, Ngāi Tūteauru, Ngāi Tūpoto) followed up her panoramic video in Pursuit of Venus with this equally ambitious and visually ravishing fusion of CGI and green screen, in which a group of Māori, Pasifika and Indigenous Australians voyage from Reihana’s tribal homeland of Hokianga Harbour to Gadigal Country, through a magical world.

The viewer follows via the camera’s point of view, soaring through the air, swooping around the steampunk waka hourua (double-hulled canoe) and gliding through the ocean.

Where in Pursuit of Venus reclaimed an old European narrative, Groundloop writes a new one, offering a joyful, futurist celebration of First Nations culture.

On display at Naala Badu, Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Warrane/Sydney.

As Above So Below (2022-23)

This dramatic, room-sized installation by fourth-generation Australian South Sea Islander Jasmine Togo-Brisby maps the hold of the 18th-century British slave ship Brooks, notorious in abolitionist literature for its inhumane conditions.

The configuration of miniature replica Tam Tams (or slit drums) from her ancestral homeland of Vanuatu represents the arrangement of bodies below deck; plaster-cast ceiling rosettes allude to the story of her great-great-grandmother, who was abducted and transported to Sydney to be a house slave for a family whose company manufactured these sorts of decorations.

Snaring us with the work’s beauty, Togo-Brisby involves us in her interrogation of history.

In the permanent collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Warrane/Sydney.