Top 50 artworks to see in Australia, part one

There’s nothing like standing in front of an artwork and be provoked into emotions, thoughts and something unexplainable. The Nightly has compiled 50 artworks you can see in Australia. Here are the first 10.

Australia has an art tradition that is unique in the world and stretches back tens of thousands of years.

This list is a teensy little blip on that timeline, 50 of the best artworks in Australian museums and galleries. Like all lists, it comes with its own list of caveats.

Firstly, what is “best”? Art is highly subjective. There are at least as many versions of this list as there are people. This is my version. Every piece here stopped me in my tracks. Many of the works changed my perspective on art (what’s possible; how it works) or more broadly, society.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.In terms of my aesthetic preferences, I’m crazy about colour and screen-based art, and get an almost literal buzz from repetition in patterns or forms. Like most people, I enjoy being immersed in a whole-of-room or immersive artwork. If there was more sound or scent-based art, I would have chosen it.

Beyond my own taste, I asked each gallery what their most popular works were, and what they considered their most “important” works in an attempt to broaden my horizons and to keep an open mind.

The resulting adventures through each gallery were an absolute ball.

Second crucial caveat: I’m not choosing from “all the art” - just the art galleries and museums choose to collect and display. The idea was to select works that readers can find and experience in the flesh, so I’ve focused on art that is on display now or in the near future.

Making the list, I felt in a visceral way how narrow a slice of “art” is in museums. There are so many reasons and manifestations of these limits, but as a simple example: there are generally more paintings on display than any other artform, and still often more works by men than women. Though most galleries are trying to redress this imbalance.

Third caveat: curation matters. No doubt there are many art works that would shine in another room, presented differently. The best art experience, I believe, is an act of theatre: it involves all the things that happen in the approach to the work, and everything going on around it - the lighting, what you can hear, other works nearby.

Finally: this list is not ranked. The works are presented chronologically, from earliest to most recent.

If you want to find out what art is in any given gallery, the major ones all have searchable online databases. Most of them have pretty reliable filters that allow you to see what’s currently on display. All the galleries featured are free, except Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art, which is privately owned.

Happy art-hunting!

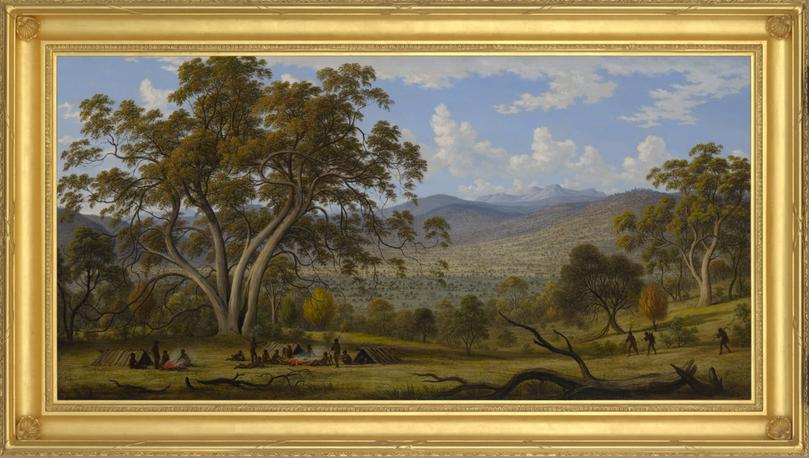

Mills Plains, Ben Lomond, Ben Loder and Ben Nevis in the distance (1836)

John Glover was significant among colonial painters in breaking from the European aesthetic tradition to forge a distinctive “Australian landscape”. His depictions of lutruwita/Tasmania, where he lived from 1831, are beguiling: the light, the colours of the bush, the expanse of nature and slightly uncanny trees.

They’re also troubling. In this painting as in others, he reinscribed palawa/pakana (the island’s Aboriginal people) into a landscape they had already been violently removed from, through the Black War. This idealised, idyllic scene ultimately reinforces the myth of “natural” colonial progress.

It’s also an ethnographic approach, presenting palawa/pakana as anonymous, tiny figures - minor details in the “wilderness”.

On display at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG), nipaluna/Hobart.

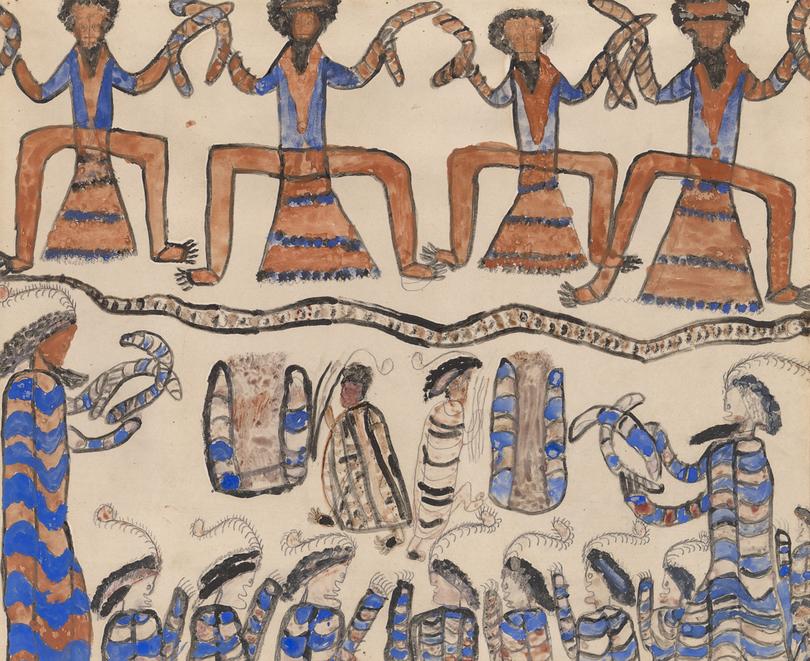

Ceremony with Rainbow Serpent (c. 1880)

This striking depiction of Wurundjeri ceremony is pictorially confident, but the use of pencil on paper gives it a feeling of rawness, or immediacy, that makes it easier to imagine the human hand that made it, and makes you feel amazed to be standing in its presence almost 150 years later.

It was made by Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung leader and activist William Barak (Beruk, to his people), one of several 19th century Aboriginal artists whose works on paper have survived (Tommy McRae and Mickey of Ulladulla are other key figures). At the time of writing, this was hanging near Tom Roberts’ Shearing the rams - a canny juxtaposition of very different contemporaneous visions of “culture”.

In the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Naarm/Melbourne

A break away! (1891)

Australian impressionist Tom Roberts captured the particular quality of light and unique colours of a drought-stricken Riverina landscape in NSW in this iconic image, one of a number of large-scale “national narrative” paintings he undertook in the 1890s.

This heroic, sun-baked vision of settler-colonial “life on the land” is cliched now, but Roberts’ painting endures, not only because of the light, colour and country, but because of his ability to conjure atmosphere and motion.

His picture feels like a freeze-frame from a film: if you press play, the dusty scuffle and clamour of bolting sheep, tumbling dog and straining rider will surge ahead.

On display at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), Tarntanya/Adelaide.

Roc Toul (Roche Guibel) (1904-05)

Australia’s so-called “lost impressionist”, John Russell, painted this luminous impression of the “savage coast” of Belle-Île, the small island off the coast of Brittany in France. Almost 120 years later, the colours still provide pure, sensuous pleasure.

Russell, a peer and friend of Van Gogh (whose work he influenced) and Monet, moved to Belle-Ile in 1888, attracted like many artists to its dramatic coastline of wild seas and fabulously shaped rocks and grottoes. However, by the time he painted this work, Russell was less interested in representing the forms of landscape than in capturing its intense colours.

On display at Queensland Art Gallery in Meeanjin/Brisbane.

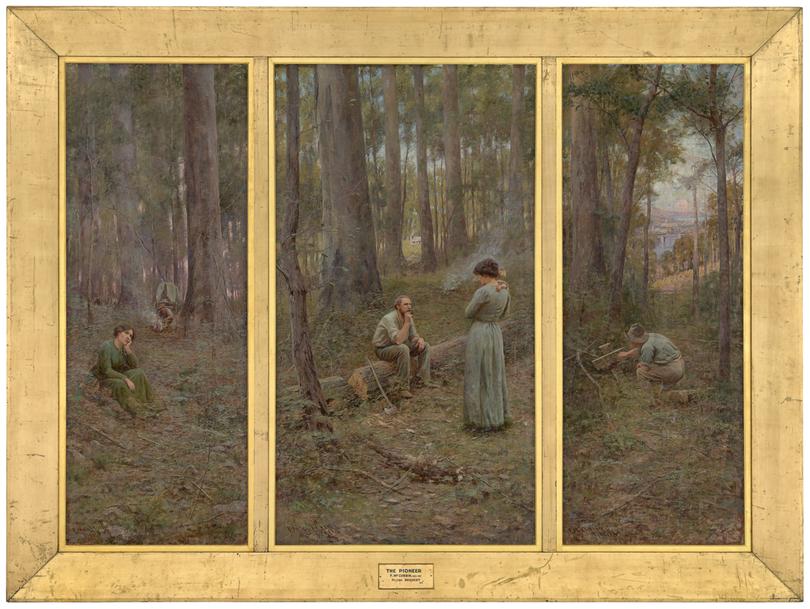

The pioneer (1904)

This massive triptych by Frederick McCubbin is the culmination of his “nationalist paintings” project, part of a broader quest by the Heidelberg school of impressionists (including Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton) to create a distinctively Australian type of art.

In his heroic depiction of bush battlers, McCubbin shows a couple arrive on their patch of land, build a home and start a family. In the final panel, we see a man, a grave and a city in the distance - signs of progress and loss, though it’s unclear if this is the original man or his son, and who has died.

On display at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Naarm/Melbourne.

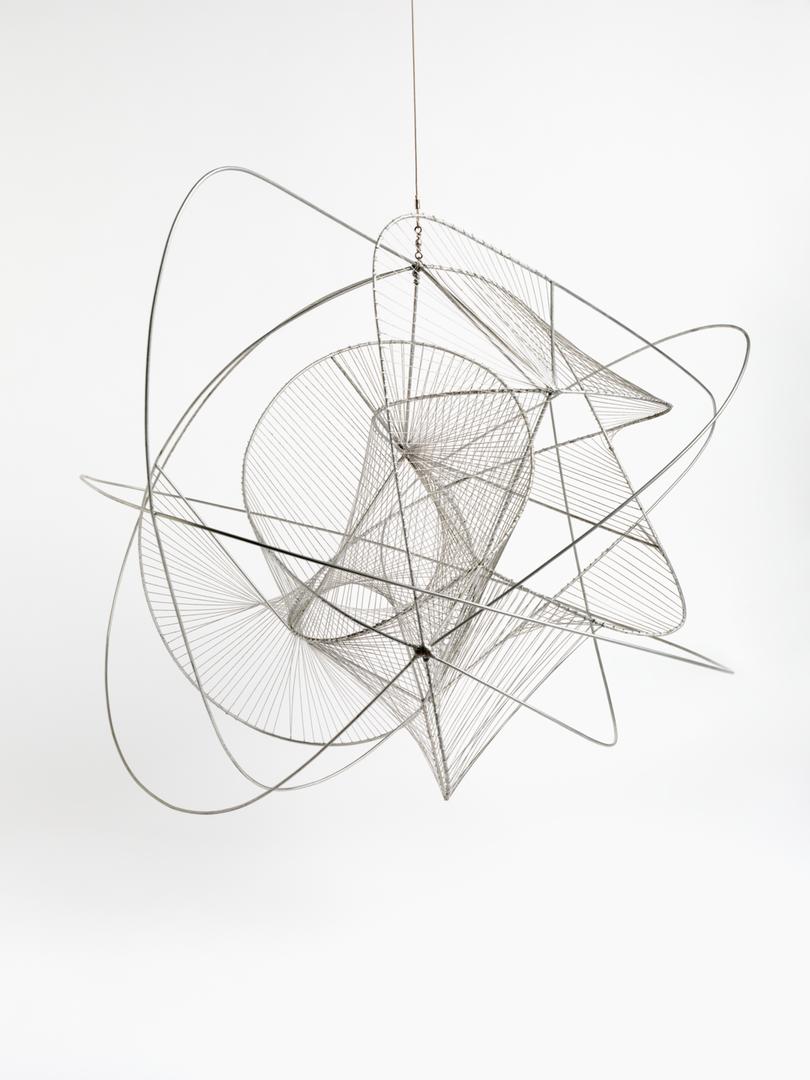

Revolving construction (c. 1957)

Artist and critic James Gleeson said Margel Hinder’s sculptures combined equal parts geometry and poetry - a particularly apt description for this kinetic mobile, which mesmerises you with the continual motion of its wire frame and its shadow.

Hinder, an American who emigrated to Sydney as a young woman in 1934 with her artist husband Frank, became a key proponent of modernist and abstract sculpture in Australia - a kind of Antipodean Barbara Hepworth (in fact the British sculptor, Hinder’s contemporary, was a key influence).

This small but captivating work crystallises her artistry with movement, light and space.

On display at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Kamberri/Canberra.

Bride and groom by a creek (c. 1960)

The composition and gorgeous colouration of this dreamlike scene are instantly compelling, let alone its mysterious protagonists. It is one of more than 30 paintings in Boyd’s breakthrough series Love, marriage and death of a half-caste (aka “the Brides”), painted in response to a trip to central Australia in the 1950s where he witnessed the shocking poverty and neglect experienced by Aboriginal people.

The Bride paintings are partially an allegory for race relations - the persecution of an Aboriginal groom and his “mixed-race” bride by white authorities - but also resonate as a broader “outsider” narrative. And they paved the way for Boyd’s extraordinary Nebuchadnezzar series.

On display at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Naarm/Melbourne.

Riverbend (1964-65)

Sidney Nolan is known for his serialised narratives: the Burke and Wills and Mrs Fraser paintings, not to mention his Ned Kelly suite (on display at NGA, a must-see). They’re strange. They’re funny. And they’re dark.

His lesser-known Riverbend series is an atmospheric treat: nine panels in hazy, thinly-applied oils, constituting a panoramic landscape of a shallow river hemmed by dense eucalypts, in which a diminutive Kelly plays hide and seek with police.

It’s usually on display in ANU’s Drill Hall Gallery, in an immersive curved display often compared to Monet’s Water Lilies cycle at the Musée de l’Orangerie. Pending renovations, it has temporarily relocated.

On display until July 28 at Canberra Museum and Art Gallery.

The American Dream (1968-69)

Encamped in his studio in New York, and fuelled by booze and drugs and outrage, Australian artist Brett Whiteley poured himself into making this electrifying 18-panel painting about a dysfunctional America - the war in Vietnam, the riots at home, the assassinations - throwing everything at it, including magazine clippings, flashing lights, a clock, a taxidermied bird, a soundtrack of police sirens and news reports.

A fibreglass shark’s maw erupts from one panel, a hole is punched through another. The peach-toned panorama starts on a tranquil dawn beach and ends with a sunset dove. In between, it’s all swirling, mutating forms, on a spectrum from dreamy to nightmarish. The climactic, apocalyptic panels are like a cartoon scream.

On display at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA), Boorloo/Perth, from July.

Pied beauty (1969)

There are many splendid John Olsen paintings in our major institutions, including Five Bells at AGNSW and its larger mural counterpart at Sydney Opera House.

This smaller, quieter work is named after one of his favourite poems, by Gerard Manley Hopkins - a poem Olsen felt was an exhortation to paint, with its opening lines: “Glory be to God for dappled things/For skies of couple-colour as a brindled cow;/For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim.” Pied beauty was painted outdoors in Cottles Bridge in Victoria, and the remarkable colours conjure a dry landscape, flecked with wattle.

On display at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), Tarntanya/Adelaide.