Top 50 artworks to see in Australia, part two

There’s nothing like standing in front of an artwork and be provoked into emotions, thoughts and something unexplainable. The Nightly has compiled the 50 artworks you can see in Australia.

Welcome to our unfolding, unranked list of the best 50 artworks in Australian museums and galleries, taking you on a chronologically arranged tour of beauty.

You can find out more about how these works were chosen in the full introduction, but simply put: this list has a single author and therefore is highly subjective but has been put together with consideration of what each gallery or museum considers to be its most important and its most popular works.

Almost all these works are on display, meaning you can go and find them in the real world.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.If you want to find out what art is in any given gallery, the major ones all have searchable online databases. Most of them have pretty reliable filters that allow you to see what’s currently on display. All the galleries featured are free, except Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art, which is privately owned.

Happy art-hunting.

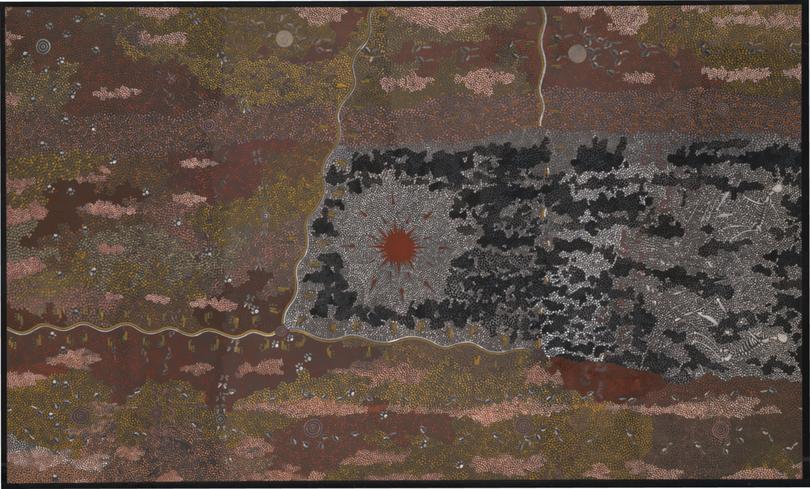

Warlugulong (1977)

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri is a frontrunner of the Western Desert art movement that emerged from Papunya, a tiny community west of Alice Springs, in the 1970s. Warlugulong is an early masterpiece of the movement, showcasing Tjapaltjarri’s deep cultural knowledge as a senior Anmatyerr man, artistic skill and inventive mind. It references several key Anmatyerr tjukurrpa (ancestral stories), the main one relating to how the ancestral fire was started. The size and narrative complexity of this painting is impressive, but even Tjapaltjarri’s smaller, simpler work Bush-fire I (also on display at NGA), one of several templates for Warlugulong, stops you in your tracks.

On display from August 31 in Ever Present: First Peoples Art of Australia at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), Kamberri/Canberra.

Iron ore landscape (1981)

When Fred Williams was studying painting in Melbourne in the 1940s, Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd and Albert Tucker were art royalty, producing heightened Australian landscapes that were the settings for human and mythological dramas. Williams was more interested in the Australian environment itself, and devoted himself to capturing it. Most famously in his abstract, immersive You Yangs landscapes of the 1960s. Then in 1979 he visited the Pilbara for the first time and fell in love with its landscapes He produced some of his best and most colourful works in response, including this vivid, disorienting painting.

On display at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Naarm/Melbourne.

The Aboriginal Memorial (1987-88)

There is perhaps no more powerful moment in an Australian museum than encountering this memorial of 200 hollow log coffins from central Arnhem Land, created for Australia’s bicentenary year to commemorate the hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people who lost their lives defending their land since 1788. Artists from nine Yolnu clans contributed groupings of poles, which are arranged in a loose geographical map of each clan’s territory, with the pathway through the installation imitating the course of the Glyde River from the inland Arafura Swamp to the sea. Pay attention to the different styles and subjects as well as the individual artistry.

On permanent display at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Kamberri/Canberra.

Something More (1989)

This early photo series is one of Tracey Moffatt’s most famous, despite many major works since (including her films Night Cries and beDevil). Like the pulp fictions that inspired it, Something More pinions the viewer with lurid colour, melodrama, sex and violence. The nine tableaux, staged on diorama-like sets with painted backdrops that appropriate iconic Australian landscape paintings, conjure an ambiguous narrative about a young woman (Moffatt, indelible in a red cheongsam) leaving her rural Queensland home in search of “something more”, but leave the viewer to fill in the gaps. It’s in these gaps - in our imaginations - that Moffatt’s vision takes root.

On display at the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), nipuluna/Hobart.

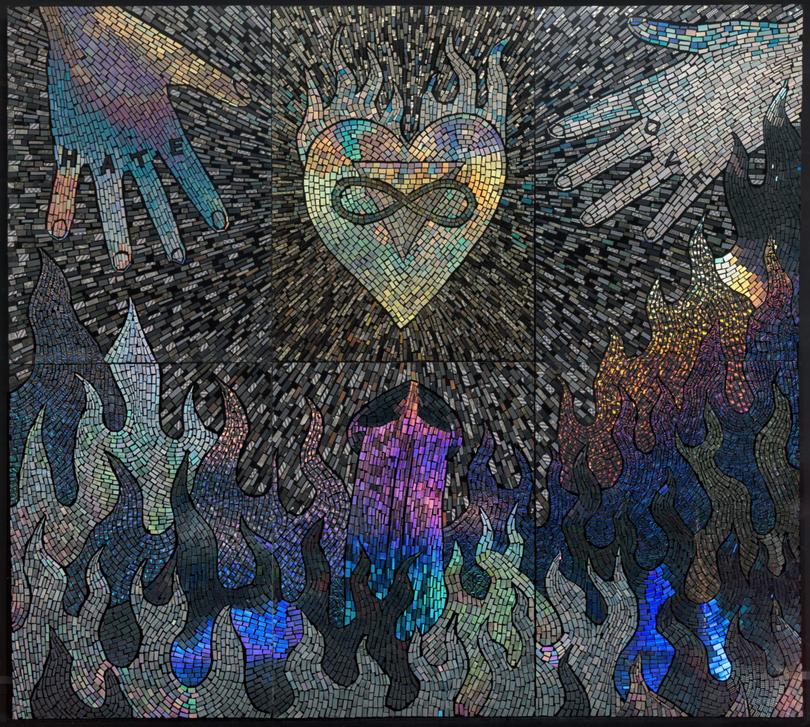

Kiss of light (1990)

Still radical and affecting decades after it was made, David McDiarmid’s Kiss of light is like a holographic holler in a quiet gallery. Given it was made at the height of the AIDS epidemic in Warrane/Sydney, when McDiarmid was losing friends and lovers (and was himself HIV positive) the joy seems remarkable; defiant. This is one of a series of mosaics he made in response to the sex and death panic of AIDS, using holographic Mylar sheeting. Whenever and wherever you find one of the works from this series, take a moment and honour the gays who went through hell in the face of government neglect and social prejudice.

On display at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Kamberri/Canberra.

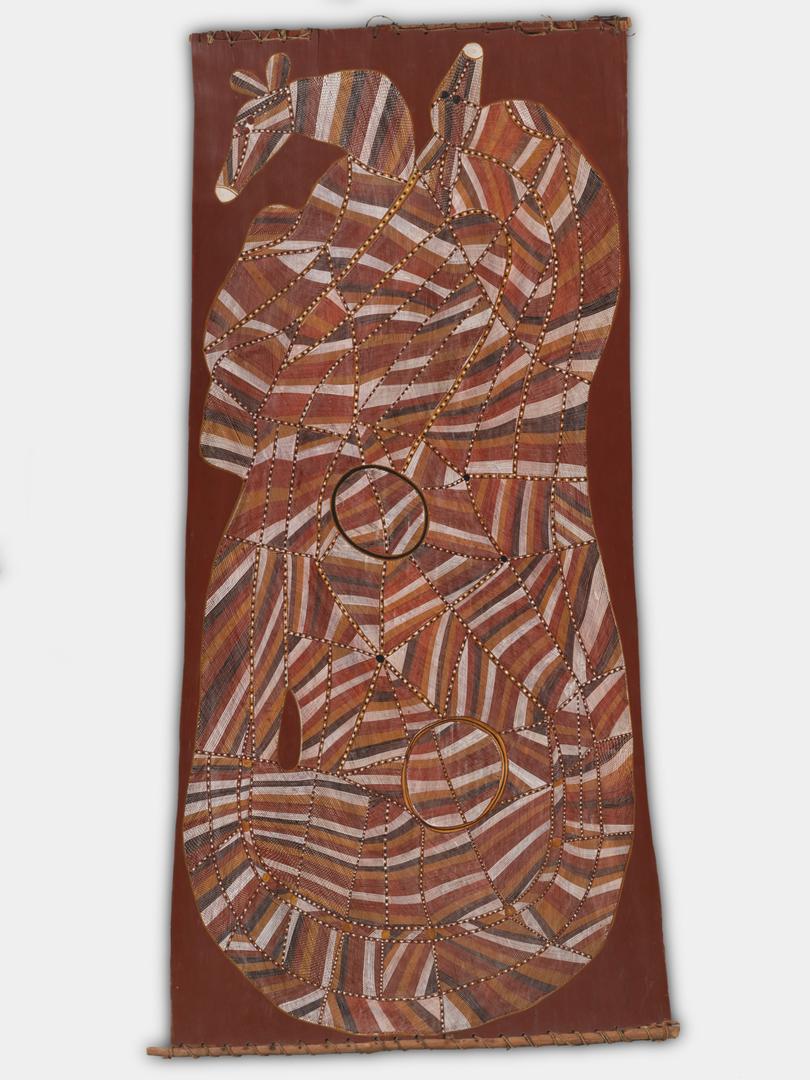

Western Arnhem Land painting is distinguishable by its fields of fine-lined cross-hatching (or rarrk) - and no-one does rarrk quite like Kuninjku artist John Mawurndjul. You can pick his work in a crowd; it’s been described as “shimmering”, radiating energy. Mawurndjul lives on his ancestral Country (west of Ramingining around the Liverpool River), using natural earth pigments to depict the Mardayin ceremony and Djang (sacred sites). Two of his lorrkon (hollow logs for burial ceremonies) are part of the NGA’s Aboriginal Memorial; hanging upstairs is this sublime bark painting, which represents a creation event involving two red kangaroo-headed Ngalyod (rainbow serpents).

On display at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Kamberri/Canberra.

Cyclone Tracy (1991)

Wangkajunga/Kukatja artist Rover Joolama Thomas profoundly shaped East Kimberley painting, and his influence is seen in the work of artists such as Paddy Bedford and Mabel Juli. Cyclone Tracy, which devastated Warmun (Turkey Creek) where Thomas lived, on December 25, 1974, was both a subject and a catalyst for his art-making. In 1975 he had a dream in which a recently deceased relative transmitted knowledge about the cyclone and Gija Country. Senior men painted these revelations on a series of boards used in ceremony, and the images subsequently inspired an art movement. This later painting shows the cyclone’s path in black.

On display from August 31 in Ever Present: First Peoples Art of Australia at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), Kamberri/Canberra.

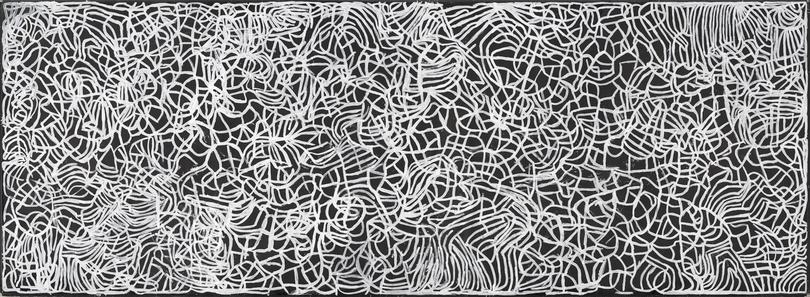

The scale and complex patternation of this monumental painting (measuring 8m by 3m) is simply gobsmacking.. Try to follow the lines and you can feel your brain start to melt. Artist Emily Kam Kngwarray (Anmatyerr) transformed the tradition of landscape painting in Australia within a few years. She was an art titan in every sense: skill, vision and success - within Australia and abroad. Famously, she only started painting in her 70s, and her grand topic was her Alhalker Country. This white-on-black painting, made the year before her death, is a distillation of technique, artistic ambition and vision, and represents her principal Dreaming: the anwerlarr (pencil yam).

In the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Naarm/Melbourne

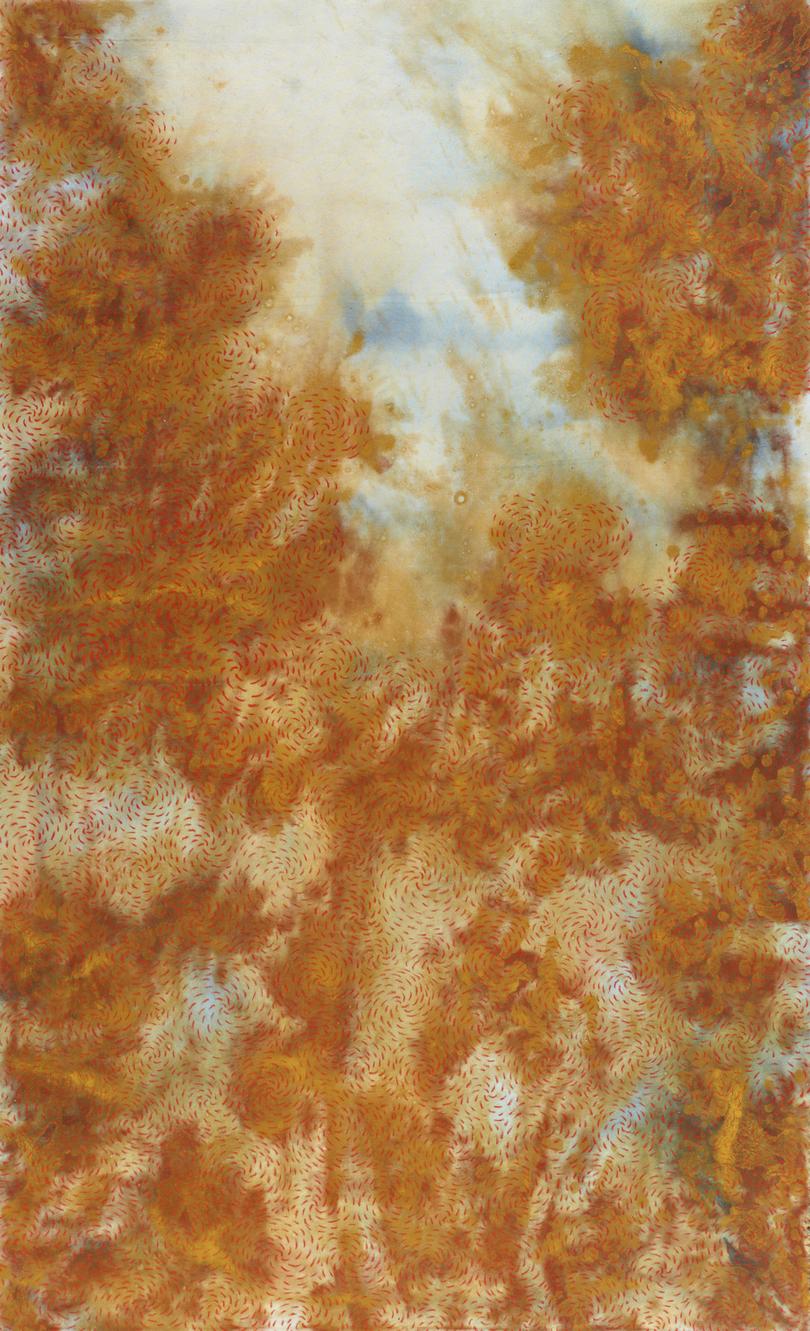

red tides (1997)

Looking at this unstretched canvas by Judy Watson it’s as if you’re underwater, gazing towards the sky. Delicate, swirling patterns of broken lines in red pastel suggest currents but also a layer of partially visible information. Watson, a descendant of the Waanyi or “running water” people of north-west Queensland, made red tides and its partner work deadly bloom for the Australian exhibition at the 1997 Venice Biennale, with that city’s waterways in mind. Her canvases conjure the pollution-induced red algae blooms in Sydney Harbour at the time, which made her think of the blood-stained waters at sites of Aboriginal massacres.

On display until August 11 as part of Judy Watson: mudunama kundana wandaraba jarribirri at Queensland Art Gallery, Meeanjin/Brisbane. On loan from the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Warrane/Sydney.

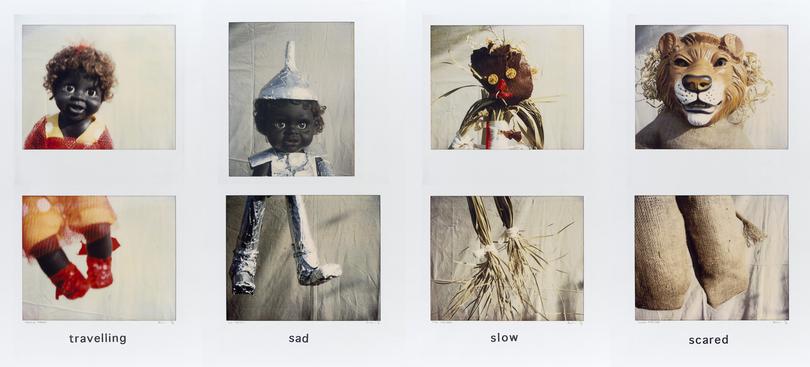

Sad, Travelling, Scared, Slow (1998) from the Oz series

The dolls feel alive in Destiny Deacon’s photos. And it often feels like they’re mid-scene, leaving you wondering what conversation or out-of-frame event you’ve missed. Sometimes, like cheeky kids, they make you smile or make you gasp. Against the odds, Deacon, a descendant of the KuKu (Cape York) and Erub/Mer (Torres Strait) people, reclaims these artefacts of racist kitsch and “Aboriginalia”, and gives them their own tender life. The Oz series, which riffs on MGM’s The Wizard of Oz, both interrogates and lampoons Australia’s national identity in the lead up to the 2000 Olympic games. This Oz is a sham, Deacon seems to say; Dorothy and her friends must cast off the roles foisted on them, and forge their own Blak/Koori identity.

On display at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Naarm/Melbourne.