Valentino Garavani, regal designer and fashion’s ‘last emperor,’ dies at 93

Valentino, as he was called, created one of the most durable and fashionable labels and became an equal of his high society customers.

Valentino Garavani, the last of the great 20th-century couturiers and a designer who defined the image of royalty in a republican age for all manner of princesses — crowned, deposed, Hollywood and society — died Monday at his home in Rome. He was 93.

His death was announced in a statement by his foundation.

Dubbed “the last emperor” in a documentary film of the same name released in 2008, and “the Sheik of chic” by John Fairchild, the former editor of Women’s Wear Daily, Garavani founded his namesake company in 1959. For the next half-century, he not only dressed a world of grandees but also became their equal, with his own palaces, movable court and signature shade of red.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“In Italy, there is the Pope — and there is Valentino,” said Walter Veltroni, then the mayor of Rome, in a 2005 profile of the designer in The New Yorker.

Perpetually tanned a deep shade of mahogany, his hair blow-dried to immobile perfection, almost always referred to by his first name (or by the honorific “Mr Valentino”) and trailed by a retinue of people and pugs, Garavani created and sold an image of high glamour that helped define Italian style for generations.

His business came into the world just before the era of “La Dolce Vita,” and he was relentless in his allegiance to that ideal. “I always look for beauty, beauty,” he told the broadcaster Charlie Rose in an interview in 2009. He was not the designer-as-tortured-artist, but rather the designer-as-disciplined-bon-vivant. He didn’t care about setting trends or channelling the zeitgeist or being on the cutting edge.

“It is very, very simple,” he told The New York Times in 2007. “I try to make my girls look sensational.”

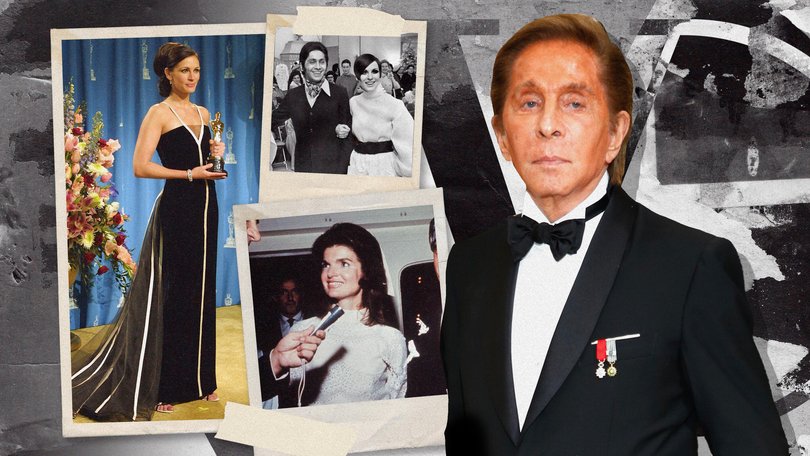

He made the cream lace dress Jacqueline Kennedy wore for her marriage to Aristotle Onassis in 1968; the sable-collared suit Farah Diba wore to flee Iran when her husband, the shah, was deposed in 1979; and the dress Bernadette Chirac wore when her husband Jacques was sworn in as president of France in 1995.

Also the draped column with feathered hem Elizabeth Taylor wore to the Roman premiere of Spartacus in 1960; the black-and-white gown Julia Roberts wore when she won the Oscar for best actress in 2001; and the one-shouldered yellow silk taffeta confection Cate Blanchett wore when she won the Oscar for best supporting actress in 2005.

In the process he — and his business partner and closest associate, Giancarlo Giammetti — also earned Italian fashion a seat in the inner circle of Parisian couture ateliers, paving the way for Italian brands that came after such as Armani and Versace; built a fortune in licences; and became the first designer name brand quoted on the Milan stock exchange. And he achieved that rare thing in fashion: a smooth transition away from the runway.

Some people work so hard they are “tortuated,” as he put it in a 19-pound limited edition oral history of his life published by Taschen in 2007. “I’m not tortuated. I’m sorry. I am not suffering. I want to be happy when I design a dress.”

Even after stepping down from his label, Garavani continued to make one-off wedding gowns for women such as Anne Hathaway and Princess Madeleine of Sweden; dabbled in opera with the costumes for a 2016 production of “La Traviata” in Rome; and cast himself as an entertaining guru, publishing a cookbook/coffee table tome that featured menus and table settings customized for his five homes around the world (and for his yacht).

“He has set the barometer of luxury,” said Reinaldo Herrera, the husband of designer Carolina Herrera and a friend of Garavani’s, in the oral history.

That book appeared just after Valentino’s 45th-anniversary extravaganza, a three-day celebration of the company planned by Giammetti, Veltroni and the Italian ministry of culture, a party so intertwined with the mythology of Rome that the implication was, as Giammetti said, that Garavani had become a “state power.”

Designing a Life

Valentino Clemente Ludovico Garavani was born May 11, 1932, in Voghera, a small town south of Milan, to Teresa and Mauro Garavani. His father owned an electrical supply company.

Valentino grew up close to his older sister, Wanda, who later worked in his business and died in 1997, leaving two sons. His aesthetic affinities were apparent early on: As a child, he requested his own cutlery and tableware. As a teenager, he asked that his sweaters be made to order so he could specify colours and patterns, and he changed the buttons on his blazers. He decided to be a designer after seeing the 1941 Hollywood musical Ziegfeld Girl, with its extravagant costumes, though he did not tell his parents until he was 17.

Supportive of his goal, they arranged for him to study fashion in Milan; six months later he moved to Paris to attend the École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne.

“I set off on the Feast of the Epiphany in 1950, with my family convinced that Paris meant hellfire and damnation,” he said in a speech in 2015 in his hometown.

After graduating, he spent five years working for Jean Dessès, a designer known for dressing the queen of Greece. Garavani said he was fired in 1957 for lingering too long at the beach in St. Tropez, but he quickly moved on to work with Guy Laroche. Two years later, Garavani decided to return Rome to open his own studio — financed by his father and some of his father’s friends — on the fashionable Via dei Condotti.

One night in 1960, not long after establishing himself in Rome, he was in a crowded restaurant on the Via Veneto when his friends asked to share a table with another young man, Giancarlo Giammetti, a second-year architecture student. So began the relationship that would shape Garavani’s life and business.

He and Giammetti became friends, and lovers for a time, and shortly afterward Giammetti quit school and joined Garavani’s business, helping him avoid an early bankruptcy and clearing a path toward global success. If Garavani aspired to be the king of Roman couture, Giammetti was his prime minister, protecting and enabling his particular vision of elegance.

Garavani’s breakthrough came in 1962, when he was invited to have a show at the Pitti Palace in Florence, then the centre of Italian fashion. He became a favourite of the social swans — Marella Agnelli, Babe Paley, Gloria Guinness — and in 1964, a year after her husband’s assassination, he met Jacqueline Kennedy, whose patronage vaulted him to global fame.

In 1968, he created an all-white collection that sent ripples through the fashion world and won him the favour of Diana Vreeland, the powerful editor, and in 1975 moved his ready-to-wear show to Paris. He created his first perfume — called, simply, Valentino — in 1978, and by the next year, was licensing his name for bags, luggage, umbrellas and handkerchiefs (also, in Japan, cigarette lighters and pens). At its height, Giammetti said, Valentino had about 42 licences. In 1984, the Italian Olympic team wore Valentino to the Los Angeles Games, and the next year President Sandro Pertini made him a Grand Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic.

Those were the boom years. The 1990s were the bad years, when grunge and minimalism, two words Valentino could never countenance, were on the rise. “I cannot see women destroyed, uncombed, or strange,” he told Vanity Fair in 2004. When he was criticised, it was for not acknowledging a popular move toward comfort and the democratization of fashion — for refusing to grapple with the complications and even ugliness of modern times.

“He is able to create a world around him, and he only lets in what he wants to let in,” Bruce Hoeksema, Garavani’s companion since 1982, said in the oral history. “A problem? He just acts like it is not there.”

Hoeksema continued, “He builds this environment where everything’s perfect and allows him to live within that world, which he needs in order to be creative.”

By doing so he also outlasted his moment, and in 1998, Giammetti and Garavani sold their company to the industrial conglomerate HdP for a reported $US300 million ($450m); the large luxury conglomerates LVMH and Gucci Group had emerged on the scene, and it was almost impossible to compete as an independent.

That began a round of owner musical chairs: Four years later HdP sold Valentino to Marzotto, a family-run textile manufacturer, who spun it off in 2005 as the Valentino Fashion Group. (Garavani was at the Milan Stock Exchange for the opening bell.) In 2007, a year after Garavani was named a member of the French Legion of Honour — thanking Giammetti, who teared up during the ceremony — the private equity firm Permira bought a majority stake in the company.

Giammetti took advantage of the transition to conceive of the 45th-anniversary gala; Permira’s officials, unused to the extravagant ways of the fashion world, were said to never have recovered from the shock of a cost that was reportedly $US10 million.

The celebration involved a dinner at the Temple of Venus and Rome overlooking the Colosseum, which was bathed in red and gold light; a runway show in the Santo Spirito in Sassia church complex near St Peter’s Square at the Vatican, followed by dinner for 1,000 in the Galleria Borghese; and an exhibition of Garavani’s work in the Ara Pacis Museum, which houses the ancient altar honouring the Emperor Augustus.

That was when Glamour magazine declared Garavani “the most important Roman in fashion since whoever invented the toga.” Six months later, after a final couture show, he retired.

“I had done enough,” Garavani said. “l didn’t want to be part of a system that is not so much about designing but about managing the companies, about money, about conglomerates. Why did I need to go through that? I had everything in my life.”

A Regal Life

What exactly that life contained was revealed in the 2008 documentary, which was directed by journalist Matt Tyrnauer and turned the designer (along with Giammetti) into a pop culture sensation.

The two men hated the film when they first saw it; they thought it was not enough about the dresses and overly personal, especially one scene in the back of a limousine in which Giammetti tells Garavani he is “too tan.” But in humanizing them, it also enshrined a way of life that the industrialization of the fashion world was fast rendering obsolete.

“Yachts, houses, paintings, entertaining, castles — none of the other designers is living that way,” Fairchild said in the oral history. “Valentino is in a category all his own. He outlives everybody.”

Though Garavani and Giammetti ended their romantic relationship after 12 years, they remained partners in every other sense of the word. In The Last Emperor, Giammetti estimated they had spent only two months apart in the almost 60 years of their friendship. They had similar tastes in suits and chinchilla-trimmed coats, as well as an understanding of each other that seemed to exist on an almost cellular level.

They retired at the same time in 2008, and after a brief period under a designer who had been brought in to the company, Alessandra Facchinetti, Garavani’s torch was passed to his former accessory designers Pierpaolo Piccioli and Maria Grazia Chiuri. (In 2016, Chiuri left, and Piccioli became sole creative director; he departed in 2024, and was replaced by Alessandro Michele). Garavani devoted himself to his other great life’s works: his social life and his homes.

Mayhoola for Investments, a Qatari fund, bought the Valentino company in 2012 (and later sold a stake to Kering, a French luxury conglomerate). Until his later years, when he stopped appearing in public, the label’s creator continued to attend its couture and ready-to-wear shows, beaming majestically from the front row.

“I hope I will be remembered as a man who pursued beauty wherever he could,” he told The New Yorker.

For him, beauty was a tool of power, and he wore it with the gilded glory of a crown.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2026 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times