Yentl at Sydney Opera House: Australian production explores gender expression and identity

Gary Abrahams, the director of a stage production of Yentl, is well aware that most people’s first — and maybe only — encounter with Isaac Bashevis Singer’s story is not the writer’s words but the Barbra Streisand movie.

Streisand’s 1983 film starred herself as Yentl, a Yiddish woman who disguises herself as a man so she can enter a Yeshiva, a religious school, and dedicate herself to studying the texts of Judaism.

As Anshl, the persona Yentl adopts, the character then meets a young man named Avigdor and his former fiancée, Hodes, and ends up in a love triangle-of-sorts.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“When we went back to the original short story, and we read it in Yiddish and in (Singer’s) own English translation, I was struck by how much more interesting and complex the original short story is. Actually, I felt the Streisand one was quite sanitised,” Abrahams told The Nightly.

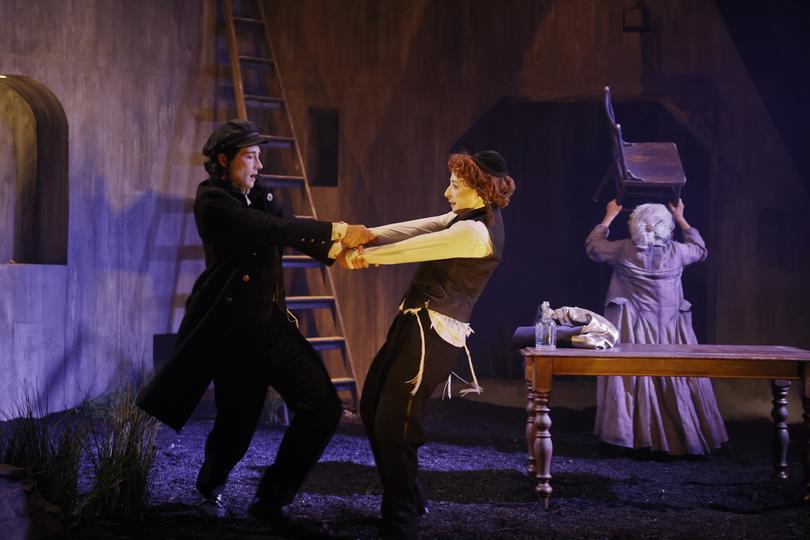

Yentl opened at Sydney Opera House this past weekend after two successful runs in Melbourne. Whereas the Streisand version had a clear feminist angle, Abrahams’ Yentl is a much stickier exploration of gender identity and performance.

This iteration is less about duality and more about merging. Think of it as Yentl-Anshl, not Yentl/Anshl. The drama frequently excavates religious texts to question whether man and woman coexist as one rather than as oppositional forces.

“Anshl was based on Singer’s sister, not officially, but she desperately wanted to study,” Abrahams explained.

“She was very uncomfortable being female. When you read about that sort of stuff, it’s very clear that with a different lens, she’s probably dealing with trans stuff, and I think those themes are inherent within the work.

“I don’t think you can read (Singer’s) work now with a contemporary understanding of identity and now not feel it’s very, very present.”

Abrahams likened the process of adaptation to archaeology, and that he and his co-writers Elise Esther Hearst and Galit Klas, dug through the original Yiddish story and discovered these complex spiritual arguments that are in dialogue with modern conversations about gender.

Actor Amy Hack joined the Yentl production for its season in Melbourne earlier this year. She said that this version approaches it through a gender expression lens.

“What Yentl is doing through this whole journey is very transgressive,” she said. “Some might say it’s bad or depraved or evil because if they’re a religious and observant person, how do you justify following such strong impulses for learning, which is transgressive with being adherent to god and the sacred texts that tell you not to do this.

“But they also tell you are being made in god’s image.”

There’s a line in Singer’s story, which is in the play, when Yentl’s father tells her that she has the soul of a man and even heaven makes mistakes. Hack was moved by the significance of those words, and she chooses to refer to Yentl using them/they pronouns.

“It’s kind of a choose-your-own-adventure and my adventure is that Yentl is non-binary,” she said.

“You can understand why (that you have the soul of a man line) would be resonant to the more fluid understandings of gender today. So, that’s how I choose to refer to them. But some people might, as Barbra Streisand did, see them as a woman who is just trying to have equality in a patriarchal society.”

Abrahams said that because many people in LGBTQI communities have had a tense relationship with religion, sometimes their experiences have been divorced from a more spiritual discourse.

“But I think we all have our own very personal relationship to spirituality,” he said. “A lot of queer people have had to wrestle on a very personal level, ‘If the universe made me as I am, how can that be wrong, how can that be unnatural?’.

“I know that sounds cheesy, but I really think this show sits within that spiritual discourse world.”

He revealed that the production had received feedback from a wide range of people from different backgrounds and faiths during the first two seasons, and that it spoke to them no matter their own cultural specificity.

The show, like its title character, is supposed to be a unifying force.

Abrahams was adamant that Yentl is not a political experience, even though he knew that some audiences felt that even coming to the show was a statement in the present climate.

Instead, the show is designed to be a piece of art that is removed from the current geopolitical conflict in the Middle East.

As he said, Yiddish is a 600-year-old language and the story is set in the late 19th century. There is no mention of Israel or any country, for that matter.

“People have a hard time separating the political discourse from anything to do with Jewish culture and Jewish themes. We’ve had a bit of a hard time, nasty comments on our advertising and all that, but I really much feel that the show is something that brings communities together,” he said.

“One of the great things when we’ve done it in the past is that you have an audience of Orthodox Jews, liberal Jews, drag queens, trans people, queer people and people from all over. Bringing all of that together feels really positive right now.”

Yentl is playing at the Sydney Opera House until November 10