The Economist: Unlike the 1987 stock market crash, the ground is shifting beneath investors’ feet

More remarkable than slumping share prices are the forces behind them

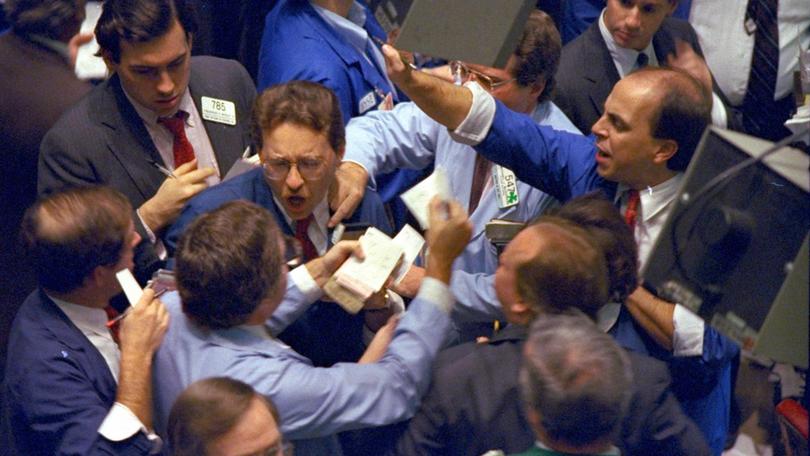

Any time share prices are slumping, it is worth looking at a chart of America’s S&P 500 index that goes back to 1987.

That year on October 19, or Black Monday, it plummeted by 20 per cent in a single day—a crash not equalled before or since.

The shock was so great that regulators subsequently devised “circuit breakers”, which automatically halt trading after a big enough drop, to prevent a repetition. Pull up a chart stretching from then to today, however, and Black Monday is barely visible, dwarfed by the scale of the subsequent returns.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.For long-term investors, what felt like an earth-shaking event at the time turned out to be little more than a blip.

Compared with that plunge, the recent lurch in share prices has seemed almost stately.

Since mid-February America’s S&P 500 index has suffered a peak-to-trough fall of just 10 per cent.

More notably, the dollar prices of Asian and European stocks rose over the same period, having already shot up beforehand, which has snapped a long streak of American outperformance.

But what has really grabbed investors’ attention is the feeling of the ground moving beneath their feet.

Although those focused on multi-decade returns might dismiss a few weeks of price fluctuations, the reverberations from recent tectonic shifts may be felt for some time.

The most obvious change is in sentiment, with the assets that were previously hottest now being shunned and vice versa. It is not just American stocks, though Bank of America’s latest monthly survey shows fund managers ditching the country’s equities at their fastest clip in decades.

They have also been dumping global shares in favour of cash. Tellingly, “value” stocks, which are cheap relative to underlying earnings or assets, have begun to trounce “growth” stocks, which are expensive but promise explosive future profits.

This reverses the trend of the past couple of years and recalls the market moves of 2022, when central bankers raised interest rates, with the consensus being that a global recession was on the way.

Investors, in other words, have gone from forecasting red-hot economic growth to a rising chance of a slowdown.

As they have made this switch, many have felt another tremor: the assets they are used to relying upon during such a “risk-off” move have suddenly let them down. Gold, it is true, has been breaking record after record.

Yet so far in March, the prices of American Treasury bonds — normally a favourite bolthole — have fallen along with the S&P. Investors are worried that persistent inflationary pressure, perhaps from a trade war that sees tariffs ratchet ever higher, might prevent rates from falling much even if growth does slow.

That keeps bond yields high and prices, which move inversely to yields, low.

The failure of the usual haven currencies has been more jarring still, especially for European investors. Stockmarket convulsions are often the cue for a “flight to safety” to the dollar and, to a lesser extent, the Swiss franc and Japanese yen.

In recent weeks, however, the Euro has soared against all three, as German and EU fiscal-stimulus plans have raised the continent’s growth prospects.

The pat on the back for policymakers has been brutal for investors who count their returns in Euros and hold assets listed overseas.

During previous stockmarket corrections, such as in 2022, a strengthening dollar acted as a hedge for such investors, cushioning their losses.

In recent weeks a weakening greenback has only added to their woes. The 10 per cent peak-to-trough fall in the dollar value of the S&P 500 index comes to 14 per cent when measured in Euros.

Meanwhile, a deeper shift is taking place that could, in time, shake markets even more violently.

For the better part of a decade, Japanese interest rates were near zero or below it.

This gave rise to the popular “carry trade”, whereby investors borrowed yen cheaply to invest in assets with much higher yields, such as stocks.

Since 2022 Japanese yields have risen fast, making carry trades less attractive; last summer the sudden unwinding of many sent stockmarkets around the world into a tailspin.

Although they then stabilised, Japanese borrowing costs have continued to rocket, reaching their highest since 2008.

Put differently, the Bank of Japan is shutting down a funding source that has fuelled traders’ bets for years, at the same time as plenty of other long-standing trends break down.

The lesson from 1987 is not to spend too much time worrying about day-to-day market movements. When the forces behind them are changing fast, though, watch out.