Budapest bathhouses: Political disputes and ageing infrastructure has led to problems with city’s adored baths

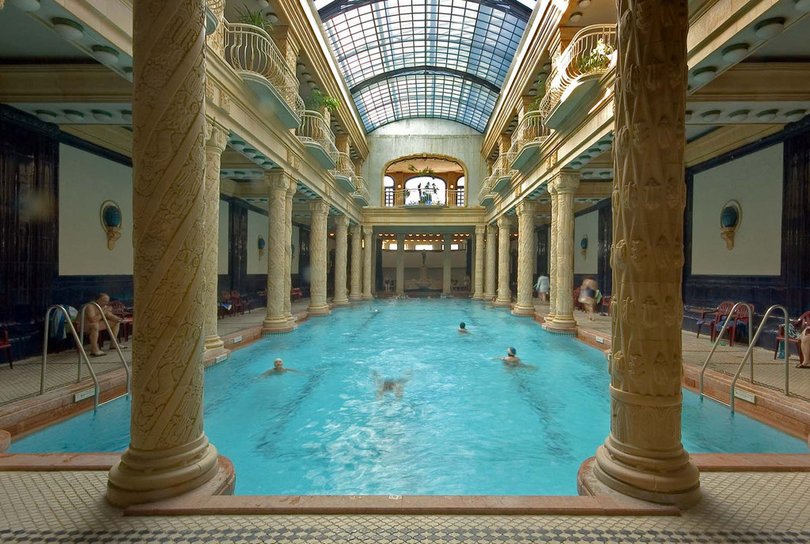

Budapest has long enjoyed the mineral-rich thermal water that flows below its surface, however, recently a number of issues has led to the deterioration of the city’s beloved baths.

Tourism in Budapest has been a bright spot in an otherwise flagging Hungarian economy. In 2024, the city drew a record number of foreign visitors — nearly 6 million, about half of whom opted to soak themselves in the capital’s famous thermal baths.

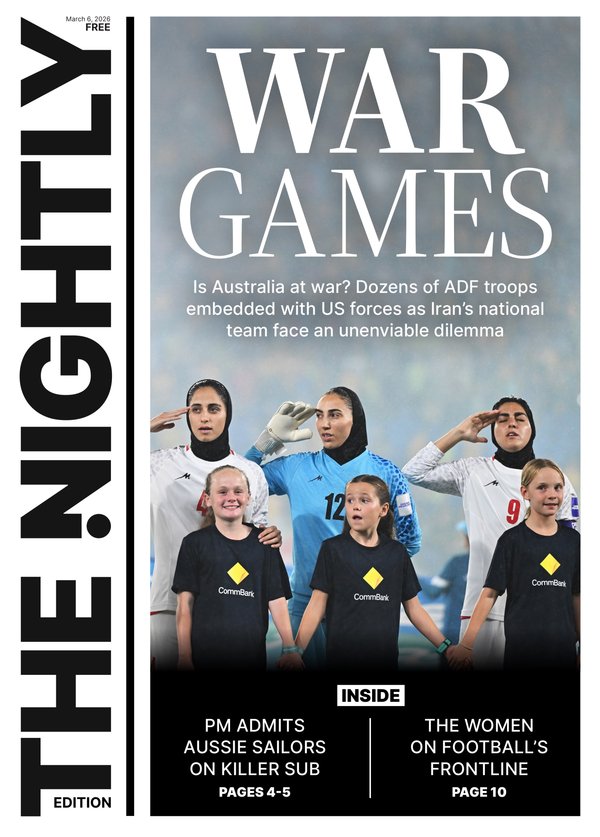

So it came as a surprise to many bathers when Gellert Bath, a grand example of Budapest’s popular baths, closed in October for renovations that won’t be fully completed until 2029.

The problem — ageing infrastructure, said Ildiko Szuts, CEO of the municipally owned company BGYH, which manages six of the city’s seven historical baths. “Gellert hasn’t been renovated since the 1970s, and we struggled every day with technical problems,” she said.

The closing of Gellert, which comes amid the longtime shuttering of two other historical baths, has upended Budapest’s finely layered bathing ecosystem by diverting tourists to the smaller baths mainly used by locals, and disrupting single-sex bathing schedules.

ROAM. Landing in your inbox weekly.

A digital-first travel magazine. Premium itineraries and adventures, practical information and exclusive offers for the discerning traveller.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It has also raised tensions between regular bathers and tourists, who sometimes defy unwritten customs, bringing their phones inside the bathing halls, for example, or wearing inappropriate attire.

“We can really feel it,” said Diana Dani, bathing director of Veli Bej, a small 16th-century bath near the Danube. On a recent Monday evening, a sign that read “the bath is full” blocked Veli Bej’s entrance, with about a dozen bathers, both tourists and locals, waiting patiently beside it.

Things got more heated at Rudas Bath, near Gellert. To absorb some of Gellert’s nearly 500,000 annual bathers, BGYH drastically curbed single-sex bathing hours at Rudas, the only Budapest bath that isn’t fully mixed.

Regulars revolted, and a group of women circulated a petition to restore the old system. They argued single-sex bathing fostered a carefree, relaxed bathing experience and helped preclude unwanted attention from men.

“If I go alone to a normal bath, sooner or later, even at my age, somebody will come up to me and say, ‘Hey, how are you?’” said Judit Pecak, 45, a bookstore owner and a regular visitor to Rudas for the past five years.

The changes have left many regulars feeling let down by city leaders and BGYH, believing they prioritise tourists and profits at the expense of local bathing communities. “They started looking only at the numbers, not seeing that there is a culture here,” Ms Pecak said.

BGYH issued a statement saying its goal was to meet the dual challenge of “preserving our centuries-long bathing traditions while keeping in mind the sales and profit considerations that enable the operation of the baths”.

As a result of the protests, the company recently reinstated two of the four single-sex bathing days at Rudas.

Budapest has long enjoyed the mineral-rich thermal water that flows below its surface, as evidenced by the remains of the city’s Roman-era Thermae Maiores.

Until the turn of the 20th century, the baths were typically simple buildings intended for local people. It was Istvan Barczy, the mayor from 1906-18, who transformed Budapest into the city of thermal baths to attract more tourists.

“Gellert was so important for Barczy that he pushed its construction to completion despite insurmountable challenges during World War I,” said Andras Sipos, a scholar and a department head at the Budapest City Archives.

Gellert opened in 1918, just weeks before the war ended. It quickly became a city landmark, attracting tourists with its spectacular Art Nouveau bathing halls and Danube-facing hotel rooms.

The bath hall remained a pillar of Budapest’s tourism even under the communist regime, which relied on precious Western visitors to boost the State-run economy.

In recent years, to capitalise on the rising number of tourists, BGYH has raised ticket prices significantly. A weekend visitor now pays 14,000 Hungarian forint (about $63) to enter Szechenyi, the city’s biggest and most popular bath.

Last year, BGYH made about $30 million in operating profits, and is broadly viewed as Budapest’s golden goose.

The fate of the two other shuttered baths, Kiraly and Rac, is less certain. Kiraly Bath was built by the same pasha, Sokollu Mustafa, who commissioned Rudas and Veli Bej in the 16th century, when much of today’s Hungary was part of Ottoman Turkey.

It closed in 2020 for renovations that are yet to begin. The building is owned by the Hungarian National Asset Management Co., a national government agency, but operated by BGYH.

Ms Szuts, who runs BGYH, said the company’s plans to move forward with renovations have been blocked by the agency. The government agency did not return emails seeking comment.

Relations between Budapest and the Hungarian Government soured when the governing Fidesz party, led by Viktor Orban, the country’s longtime prime minister, lost its majority in the City council in 2019 to a centre-left coalition led by the current mayor, Gergely Karacsony.

Since then the Government has demanded that the city drastically increase its “solidarity contributions” to other regions in Hungary, an escalation of a program that forces wealthier municipalities to help support poorer ones.

While the municipality of Budapest was a net beneficiary of State funds under the previous mayor, this year it is required to contribute about $405m to the central government, which accounts for about 20 per cent of the city’s annual budget.

“It’s a political punishment,” said Ambrus Kiss, director-general of the mayor’s office.

Marton Nagy, Hungary’s economy minister, disagrees. In a recent Facebook post, he said Budapest’s financial troubles were caused not by the solidarity contributions but by the mayor’s “catastrophic” leadership, and that well-off cities had to support less developed regions in Hungary.

“The catch-up of the countryside is our common interest,” he wrote.

A few years ago, BGYH bought Rac, a bath that has been out of service since 2002, with the intent to finally reopen it. To do so, BGYH requires a loan — but as of 2012, only the Government can decide whether a municipality is permitted to take one out.

“These decisions aren’t based on professional considerations; they are political,” Mr Kiss said. If the loans aren’t approved, Gellert and Rac will not be renovated, he added. the Ministry for National Economy did not respond to questions about BGYH’s pending loan application.

Outside Budapest, the Government has generously supported bath-related investments in places such as Gyula, a town near the border with Romania, and Lakitelek, a village in the Great Hungarian Plain.

The city of Gyor, for example, received about $97 million for a state-of-the-art thermal bath project, which is now struggling to attract customers.

While Budapest accounts for more than half the visitors to Hungary, comparable investments are not being made in the capital’s thermal baths.

Ms Szuts believes the Government’s approach defies the tourism strategy advocated by the economy minister.

“Gellert is an icon of Budapest and Hungary, but nobody in the Government wants to give us some money,” she said.

The hotel abutting Gellert Bath was recently bought by BDPST Group, an investment company run by the prime minister’s son-in-law, Istvan Tiborcz.

He has accumulated a portfolio of upscale hotels within Budapest’s city centre, often financed by loans from government-friendly banks. Gellert Hotel is currently undergoing a renovation and is expected to reopen in 2027 as a luxury Mandarin Oriental, targeting wealthy tourists.

Peter Magyar, the Opposition Leader and a contender with Orban in next year’s national election, has speculated that the bath may ultimately land in the hands of the prime minister’s son-in-law. (Mark Nemeth, the head of public relations for BDPST, said in an email the company has no intentions for the bath.)

Mr Kiss refuses even to entertain such an idea. “It makes no sense to sell Budapest’s greatest assets,” he said. “What would be next, Szechenyi Bath?”