Berlin, a city known for its urban grit, is making a comeback for its old-world grandeur

Once coveted by travellers for its urban grit, today Berlin is just as renowned for its grace, where old-world grandeur is making a serious comeback.

Berlin is a city of profound contradiction. Poor. Bourgeois. Ancient. Futuristic. Ugly. Sexy. Few cities carry such a befuddled mosaic of conflicting identities.

The German capital, however, embraces its distinct personality crisis with vigour and verve. As cities go, Berlin has seen it all ... and just a little bit more. This front-row seat to history — and the future — has endowed its denizens with an “anything goes” philosophy: which has seen countercultures erupt, tolerance flourish and transfiguration embraced.

While Berlin appears forever in a dizzying state of evolution, its foundations are perfectly antediluvian, born of a Slavic settlement dating back to the late Middle Ages, eventually emerging as the august capital of the Prussian Empire in the 18th century, and later a unified Germany.

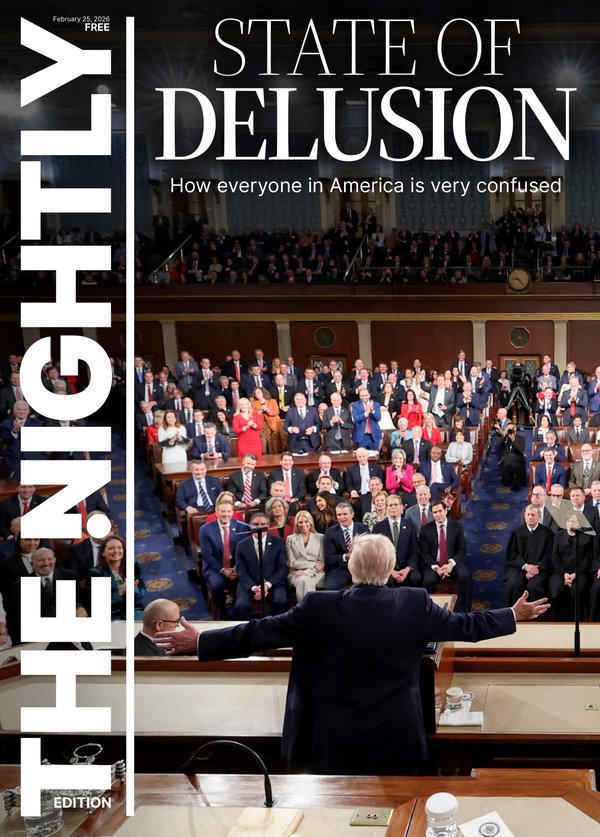

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Much of these regal chattels was erased from the maps after World War II when Berlin was left ruined, cleaved and quartered. And what was not physically erased was largely expunged from the collective consciousness of a people wanting to leave the past behind and embrace a new and prosperous future.

But as the city keenly embraced a radical new persona with the collapse of the Berlin Wall — a bacchanalian bender of clubs, kebabs and concrete — much of the city’s heritage remained, albeit often out of sight and out of mind.

As the city enters a new epoch, however, this heritage is being reawakened and reclaimed, its gilded architecture renovated, is bucolic fringes rediscovered, its historic pedigree of elegance reimagined.

Best known for its epicurean embrace of the 24-hour party, Berlin’s inner city also boasts many immaculately preserved historic districts, where the zeitgeist and opulence of the Wilhelmine epoch and unbridled panache of the Weimar Republic live on.

Among the most winsome districts are Prenzlauer Berg, Kreuzberg and Charlottenburg, the latter once written off as vainglorious and fogeyish, but now making a staggering revival with some of the finest baroque, neoclassical and Grunderzeit architecture in Germany, lavished with soaring ceilings, marbled lobbies and elaborately embroidered stucco facades. To stroll these streets is to travel back in time.

Charlottenburg is also home to the district’s eponymous and sumptuous 17th-century palace — named for the beloved wife of Frederick I, King of Prussia — as well as the city’s most storied department store, the timelessly graceful KaDeWe, dating back to 1907 and still an epicentre of food and fashion today.

However, it is in the outer districts at the city’s margins where this alternative old-world Berlin truly reveals itself: a fantasia of lakeside villas, bucolic forest and old-world eateries. Lichterfelde, Zehlendorf and Dahlem to the south-west are the finest example of these, all easily accessible via Berlin’s suburban rail network.

Here, fringing the gaslit cobbled lanes you will find the Berlin of reverie: historic villas and mansions styled as mini chateaux — each truly distinct and ranging in architectural style, and once home to Berlin’s aristocratic class of the 19th century.

Much of this area was mercifully spared Allied bombs and would later become home base to the United States military’s Berlin Brigade following World War II. Here quaint village squares give way to the verdant Grunewald, a wild inner-city forest that is buttressed by rivers and lakes — none more seductive than the Schlachtensee, a glacial lake hemmed by birch, chestnut and oak trees where Berliners come to bathe, row wooden boats and drink in the sublime majesty of nature.

The Fischerhutte (Fisherman’s Hut) on the lake’s eastern reaches is home to the city’s most picturesque beer garden, where mugs of generously overflowing wheat beer are coupled with pretzels so enormous they were evidently catered for the giants of Brothers Grimm German folklore.

Folklore runs deep here, from the castles that punctuate this verdurous and ancient landscape through to the otherworldly Pfaueninsel (Peacock Island): a portal back to another century, where animals roam wild between the royal manors of an isle floating in the middle of the Havel River. And just to the south Nikolskoe, a hunting lodge built for the visit of Russian Tsar Nicholas I, and today a restaurant serving up the wild bounty of the greater Brandenburg region in yesteryear’s splendour, amongst the fare deer and boar accented with local forest berries.

A little further south is Wannsee, the city’s largest lake and home to its most historic lido and a stately array of villas. Among them is the House Of The Wannsee Conference, the imposing mansion where the nazi leadership mapped out its sinister Final Solution, which is now a museum. Nearby is the charmed abode of leading German Impressionist painter Max Liebermann; today it is a cafe and gallery. And a little further north-east the Brucke Museum, a deeply affecting exploration of the artistic style that would immediately follow in the tumultuous decades of the early 20th century, German Expressionism — branded Entartete Kunst, or degenerate art, by the nazi party.

Back in the city centre upon the fabled Unter den Linden — cosseted between the wholly reconstructed Berlin City Palace, the gracious 18th-century Gendarmenmarkt square and the plush Tiergarten royal hunting grounds — I pull up a table at the Adlon Kempinski Hotel, once the playground of Albert Einstein, Marlene Dietrich and Charlie Chaplin. The waiter delivers one of the hotel’s specialities: a fine-dining riff on the city’s most emblematic street food, the doner kebab. Never has a personality crisis tasted so delectable.