The Nightly On ... Influence: What does it mean to be influential in 2025?

Social media continues to redefine what influence looks like in the modern world. But what does it really take to shape the lives, beliefs, conversations and, sometimes, the spending habits of others?

If you ask an AI image generator to create a picture of a typical influencer, it spews out pretty much what you would expect.

The young woman’s hair is glossy, her smile is big and her cleavage considerable. She is grinning into her phone.

Tweak that to request an image of a typical influential person and you get a picture of a middle-aged man in a suit and glasses, with a haircut that would not look out of place in the 1950s.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.This two-minute experiment proves nothing except that artificial intelligence is still struggling to understand what influence really means in an age of influencers — just like the rest of us.

The concept of influence goes back to the ancient Greeks and is more nuanced than “the ability to get others to do what you want by making them want to do it”, which was the premise at the heart of Dale Carnegie’s seminal self-help book on the topic.

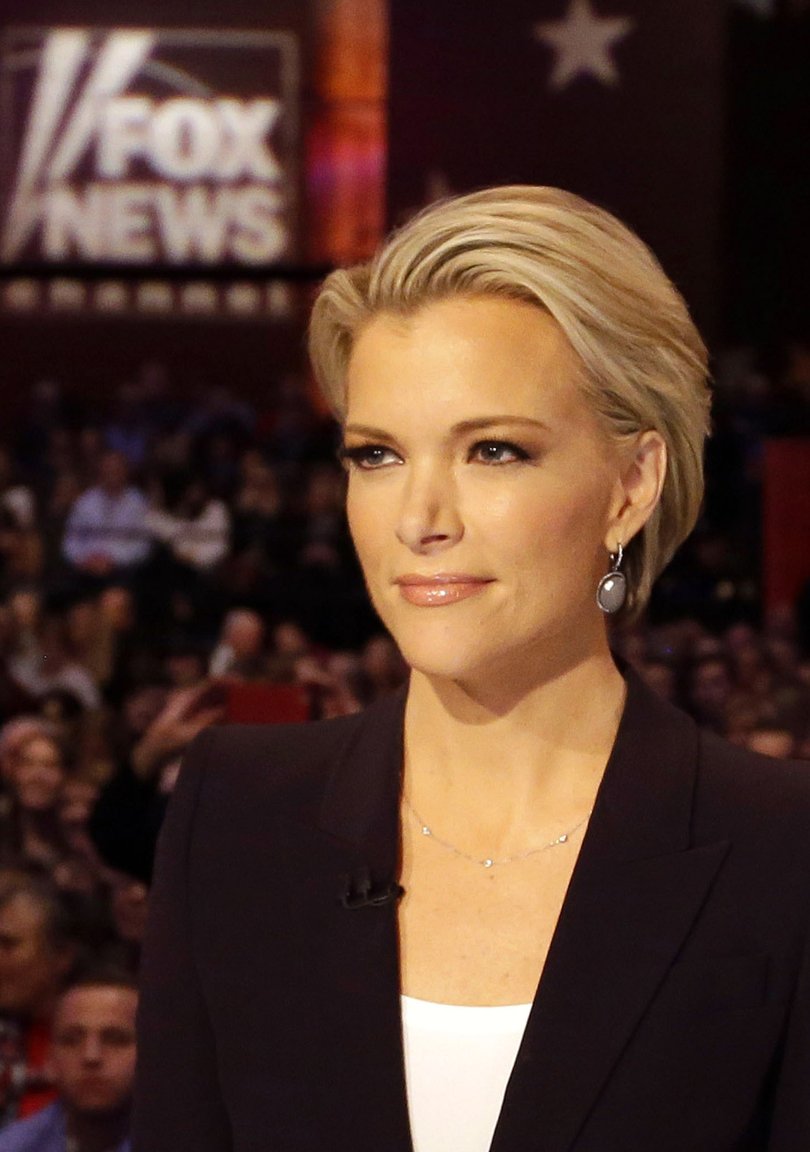

A glance at Time Magazine’s 2025 most influential list tells some of the story: from US President Donald Trump to journalist and podcaster Megyn Kelly and Australia’s own Andrew Forrest, to be influential is to shape the lives, beliefs, conversations and, sometimes, the spending habits of others.

This influence-themed edition of The Nightly On has sought out those at the top of their game across politics, sport, business and entertainment; from the head of the Australian Olympic Committee Mark Arbib, who will shape Australia’s hopes ahead of Brisbane 2032; to Kyle Sandilands, the outspoken radio host who has ruled Sydney’s airwaves for decades; and newly re-elected Minister Katy Gallagher, who will use her dual portfolios of finance and women to put financial abuse loopholes in her crosshairs in 2025.

It also dives into the world of online influencers and how they have made a business out of being influential.

Behavioural change expert and Monash University professor Liam Smith says most people want to be thought of as influential — for good reason.

“There’s a natural inclination in many people to want to be influential because of deep-seated psychological and evolutionary drives,” Smith says.

“From an evolutionary perspective, those who were influential probably had better access to food, water (and) shelter.

“Psychologically people are social beings, meaning we seek status, recognition and belonging.”

In other words: “It’s human nature to want the approval of peers.”

The desire to be influential may be timeless, but the question of who gets to have influence and how it is wielded has changed.

For as long as political leaders, corporate bosses, the media and religious rulers have existed, they have had influence. Their decisions have real-world consequences: they can move stock markets, kill or create jobs and shape society’s values.

But the erosion of public trust in institutions, from political parties to the Church, and the rise of social media has paved the way for a new of breed of influencers.

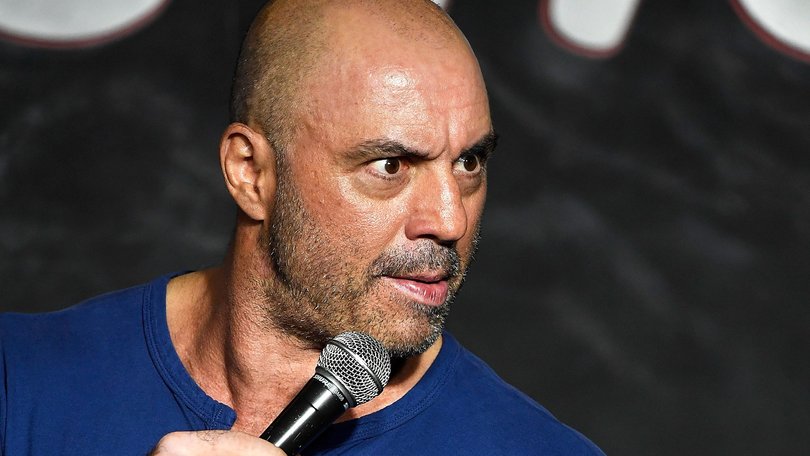

In the US the “Joe Rogan effect” is such that Trump’s appearance on the popular podcaster’s show — and Rogan’s subsequent endorsement of Trump — was seen as a turning point that helped clinch the young male vote. Presidential candidate Kamala Harris was so keen to appear on a popular rival podcast, Call Her Daddy, that her team reportedly spent a six-figure sum building its own version of the set.

Australia’s Federal election saw Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and then-Opposition leader Peter Dutton hit the podcasting circuit, with those appearances subsequently sliced and diced for TikTok, YouTube and Instagram.

There is logic to that: nearly half of all Australians, not just young people, now access at least some of their news on social media. The numbers are higher for gen Z and millennial voters, who collectively have overtaken baby boomers as the biggest voting bloc.

Smith said “normative influences” — meaning individuals or groups whose opinions someone cares about — can be particularly influential to young people. So it makes sense for politicians to try to tap into this source of influence.

“A hundred years ago, it would have been peers in the schoolyard or at work that they’d listen to,” he says. “In a hundred years time, there’ll be other normative influencers . . . maybe AI-generated robots — who knows?”

There is irony in the fact that the public figures who wield the most influence in the political, corporate and creative worlds would likely run very fast away from being labelled someone “of influence”.

Academic Jonathan Albright says even those who find the world of online influencers appealing — bypassing as it does traditional routes to power — could be uncomfortable with the label.

“What we’re seeing in 2025 is a fundamental split in how influence operates,” says Albright, a senior lecturer at the University of Western Australia.

“It’s now a dual-currency system where people must simultaneously appeal to human audiences and algorithmic systems. This creates the paradox ... everyone wants influence but many reject the ‘influencer’ label because that term invokes the machinery behind what’s supposed to feel authentic and organic.”

Cheek Media chief executive and Big Small Talk podcaster Hannah Ferguson is one popular Australian commentator pushing back on the extent to which the term influencer is applied to particularly women using online platforms.

“The agenda is clear — to undermine our intelligence, to paint us as untrustworthy, and to conflate us with green juice and a discount code,” she told the National Press Club in May. “There is nothing wrong with being an influencer, but the label is intended to cause significant reputational damage. The impact is deeply misogynistic.”

Interestingly Ferguson is now flagging a Senate run, chasing a different kind of influence.

What we’re seeing in 2025 is a fundamental split in how influence operates. It’s now a dual-currency system where people must simultaneously appeal to human audiences and algorithmic systems.

Catherine Archer is an expert in influencers at Edith Cowan University. She says while sources of influence may change over time there are still some constants, whether you are talking about Canberra, the boardroom or TikTok.

People tend to be influenced by those based on three categories: competence, appearance or rank, she says.

And regardless of the changing face of influence, a person’s character — or at least other people’s perception of it — remains as important as it ever was.

“Influence is a very old concept, all the way back to the Aristotelian concept of ethos, pathos and logos,” she says. “And the ancient Greeks were on to something when they said a person’s character would affect their influence.”