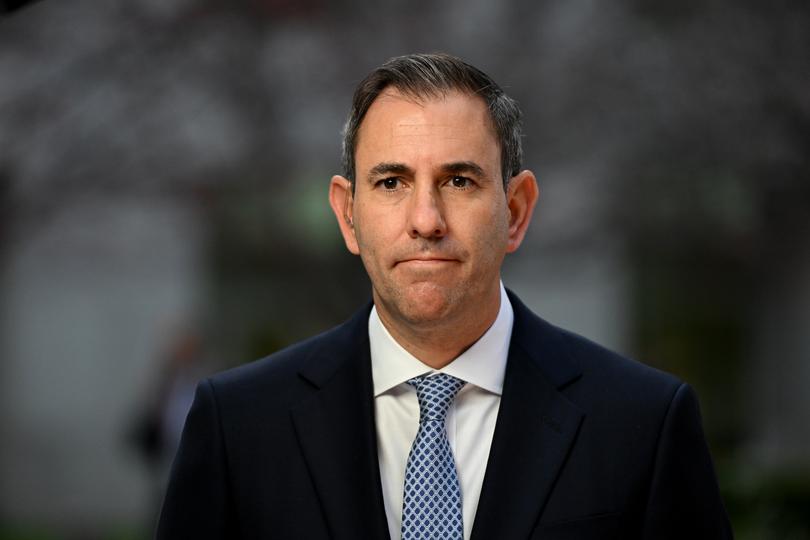

BEN HARVEY: As the economy slides, Treasurer Jim Chalmers looks for someone to blame

BEN HARVEY: Jim Chalmers knows he can’t blame the vagaries of faceless world markets for Australia’s economic predicament. But he can blame RBA governor Michele Bullock.

Like just about every treasurer Australia has ever had, Jim Chalmers never studied economics.

His PhD is in political science and the good doc has been playing to his strengths, lacing the current debate about monetary policy with a healthy dose of real politik.

Jim stated the bleeding obvious this week when he said the Reserve Bank was smashing the economy through rate rises.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.He was just telling it as it was, the Treasurer said. What weasel words; the tenor of the delivery and the language chosen gave lie to any thought this was a benign observation about interest rate policy.

Chalmers was having a crack at Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock. He knew it, she knew it and a bunch of other gutless politicians clearly knew it because it gave them the “courage” to join the “debate” about monetary settings.

Two days later it was nothing short of a full-blown pile-on. Given half the chance, some of those quoted would have paraded Michelle through the streets as they shouted “shame”.

It was a coordinated intimidation campaign aimed at pressuring Australia’s most important public servant into dropping her tough-love rhetoric and becoming an interest-rate dove.

Apparently, this woman is not for turning, for Bullock put the mouthguard in and doubled down.

More rate rises were on the cards, she warned defiantly, and if that meant over-extended homeowners selling their houses and moving somewhere cheaper then so be it.

This would have frightened Gen Y, who was forced to confront the possibility of living in a house with no alfresco kitchen or parents’ retreat*, and it would have positively terrified Chalmers, for two reasons.

First, as a cuddly lefty, he is loath to condemn a generation of Australians to houses containing just one bathroom and no butler’s pantry.

Second, he doesn’t want to be the first treasurer since Paul Keating to oversee a recession. Especially with an election looming.

He is right to be scared (at least about the second part).

Most readers would know that an economy is considered to be in recession if it records two consecutive quarters of negative growth — negative growth being one of those infuriatingly nonsensical terms economists love to use (“upside risk” is another) so the rest of us feel dumb.

This line in the sand is completely arbitrary.

Nobody would notice the difference in living standards in two consecutive quarters of 0.1 per cent growth versus minus 0.1 per cent. It’s not like you wake up in a shantytown should the economy contract so imperceptibly.

When America’s economy slipped backwards twice in six months in 2022, thereby going into technical recession, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen shrugged it off.

Recessions, she said, were characterised by layoffs, business closures and a slowdown in spending and that wasn’t happening. The economy, rather, was “in transition”.

Some economists agree with Yellen. They say the strict mathematical definition is stupid and that there are better ways to decide whether an economy is travelling well.

As you can read below, some of them are quite quirky.

* The R-word index. This measure, which is based on how many times the word “recession” appears in the media, was invented by the Economist in the 1990s and was used to accurately call the real-life contractions of 1990, 2001 and 2008.

* The undies index: Former US Federal Reserve boss Alan Greenspan thought blokes put off buying new daks when times were tough and it proved true in the GFC and the COVID-inspired world recession.

* The champagne index: Consumption of the fancy French fizz peaked in New York right before the 1987 stock market crash and then everyone was back on prosecco.

* The lipstick index: In the early noughties Estee Lauder heir Leonard Lauder noticed that sales of lippy went up when the economy went down. He surmised that women, and some men, spent more on little treats to make themselves feel better when times were tough. Apparently Lauder was onto something because data analytics firm NPD tracks 14 discretionary retail spending categories and beauty products are the only ones that go up during a recession.

* The hemline index: This has been around since the Great Depression and surmises that skirts get shorter when things are good (right now we are more Handmaid’s Tale than Twiggy’s mini).

* The cardboard box index: This isn’t about how many people are living in them; it is a count of how many boxes are being used to transport manufactured goods and is therefore a quasi-measure of industrial output.

* The tech-hiring index: Also known as the “nerd marker” this index monitors how many information technology staff are being laid off at any given time. The thought is bosses will cull back-room workers before they touch customer-facing employees.

Regardless of which measure we use to call it, Chalmers knows that a recession will be perceived as rude evidence of his failed economic stewardship.

I use the word “perceived” advisedly because the reality is politicians have little control over what happens in an economy.

They are the captains of tiny boats being tossed around by the gigantic swells of the world’s financial markets.

If you want to contextualise just how powerless someone like Jim Chalmers is against such forces consider these statistics.

The Australian Federal Budget — the total amount of money that the Government spends each year — is about $600 billion. That’s what it costs to run Australia for 12 months. The country’s gross domestic product is $2.5 trillion.

They’re big bickies in isolation but mere rounding errors in the context of the worth of all the stock markets on earth ($160 trillion) or the value of the world’s bond market ($200 trillion).

What hope for Captain Jim in the good ship HMAS Canberra? The best he can do is knock the rough edges off market cycles with a bit of stimulus spending. The reality is if the bond market sneezes Jim won’t just catch a cold; he will need to be intubated.

Chalmers knows he can’t blame the vagaries of faceless world markets for Australia’s economic predicament. But he can blame Bullock.

* Fear not, Gen Y, the generations that came before you managed quite well without alfresco kitchens (we called it the “barbie area”) or parents’ retreat (which were known as “the shed”).