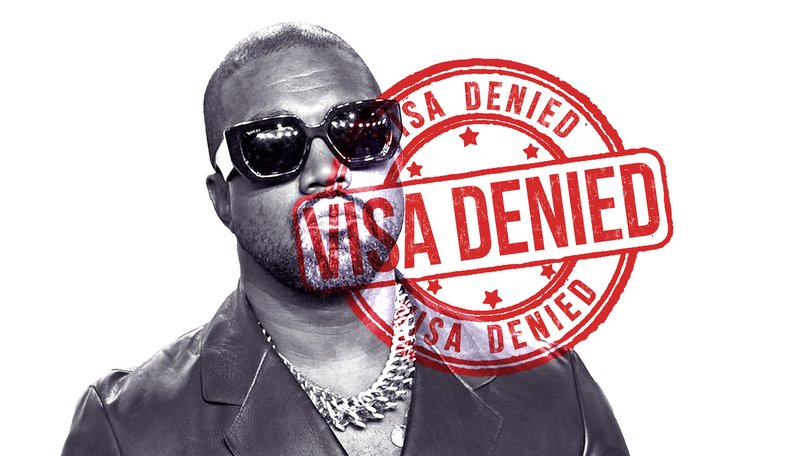

DVIR ABRAMOVICH: Why the Ye ban matters as Australia sends a message to the world on bigotry

DVIR ABRAMOVICH: Declaring Kanye West isn’t welcome in Australia sends a powerful message that celebrity doesn’t diminish bigotry.

A few years ago, I was walking through a Holocaust museum when I came across a display case containing a child’s shoe. It was small, worn, and brown.

The tag said it had belonged to a boy murdered in Auschwitz. I stared at it longer than I expected. Not because of what it meant about the past, but because of what it demanded in the present.

This week, Australia answered that demand.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Immigration Minister Tony Burke announced that Kanye West, one of the most influential artists of our time, would not be allowed to set foot on Australian soil.

The reason? A song. A song titled “Heil Hitler”.

A track that samples Nazi propaganda, glorifies the man responsible for the murder of six million Jews, and spreads the kind of hatred that once lit up Europe in flames.

West is not an ordinary celebrity. He is not a fringe provocateur. He is a global icon with millions of fans, a man who can sell out stadiums, flood streaming charts, and dominate headlines with a single post.

When someone like that chooses to exalt Hitler and make nazism part of his brand, it doesn’t just cross a moral threshold. It alters the standards for everyone else.

In an age where outrage is often hollow and consequences are temporary, Australia’s refusal to host Kanye West was not just a visa decision. It was a statement of national character.

We live in a world where anti-Semitism is rising again. In subreddits and schoolyards. In whispers and graffiti.

And too often, when it emerges in polished, fame-wrapped packages, people look the other way. They call it performance art. They say it’s mental illness. They invoke free speech.

But no one ever asks what it costs the child who walks past a swastika carved into a desk. Or the survivor who sees Hitler trending.

We forget that hate doesn’t have to shout to be heard. Sometimes, it plays on repeat. Sometimes, it goes viral.

Kanye West’s descent into open anti-Semitism has not been sudden. It has been a long, visible unravelling.

For years, Kanye West hast been testing how far fame can shield someone from consequence. He has tweeted that he’s going “death con 3 on Jewish people.” He has appeared on national television praising Adolf Hitler. He has sold clothing with swastikas. He has told tens of millions of followers that he is a Nazi and proud of it.

It culminated in something unmistakable: admiration for Adolf Hitler and a song released on the anniversary of Nazi Germany’s defeat. What began as erratic provocation hardened into ideology. And with every platform that gave him airtime, the damage deepened.

But Australia said no.

It said no to the normalisation of nazi language. It said no to the re-branding of bigotry as art. It said no to the idea that celebrity justifies moral indifference.

And in doing so, it reminded us that borders are more than markings on a map. They are declarations of principle. They show the world what a country is willing to tolerate and what it is not.

This is not about silencing a voice. It is about refusing to elevate one that celebrates mass murder.

Because silence legitimises. And platforms amplify.

When someone with Kanye West’s reach tells millions of listeners that Hitler was misunderstood, it doesn’t stay theoretical. It shows up in the real world. On a Park in Melbourne with the words “Kanye is right”. In classrooms, Jewish students have been taunted with West’s words. In extremist forums, his lyrics are quoted as gospel.

Some will say banning him is censorship. But this isn’t about suppressing opinions. It is about refusing to reward a person who turned genocide into a hook. It is about marking the boundary where tolerance ends.

Others will call it performative. But gestures matter. They ripple outward.

They tell a teenager in Melbourne or Sydney that their government stands with them.

They tell a Holocaust survivor that the past will not be trivialised. They tell the world that open societies are still capable of making clear, principled decisions.

In recent years, we’ve grown accustomed to letting things slide. We tolerate the intolerable because we’re afraid of overreacting. But sometimes, the greater risk is underreacting. Sometimes, the right thing isn’t to argue, but to close the door.

What Australia did this week wasn’t loud. It didn’t come with hashtags or protest marches. It was, in many ways, beautifully ordinary, a simple decision made in a minister’s office.

But its implications echo far beyond Canberra. They reach into the moral architecture of every democracy struggling to hold the line.

Because hatred never knocks. It slinks in. It wears Yeezys. It samples evil and calls it rhythm.

And every so often, a nation has to look it in the eye and say, with quiet firmness: “Not here.”

Dr Dvir Abramovich is Chair of the Anti-Defamation Commission and the author of eight books.