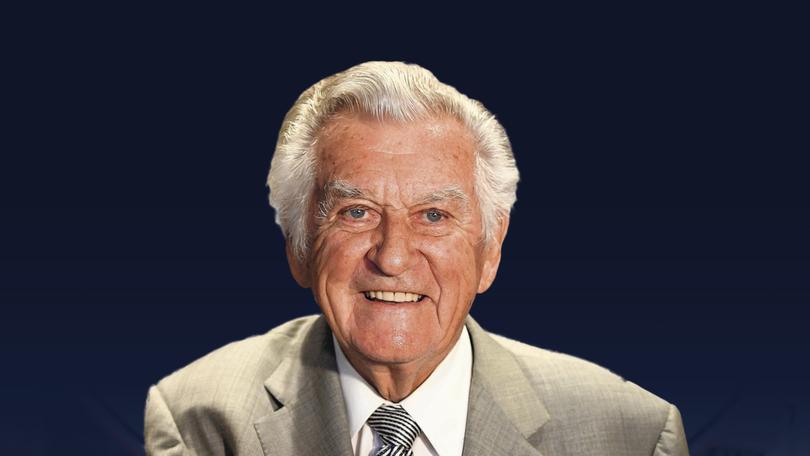

EDITORIAL: Where are the Curtins and Hawkes of the 21st century?

EDITORIAL: The truth is it’s much more difficult to be a successful leader today than it was in the eras of Curtin, Hawke, or even Howard. Here’s why.

A generation or two ago, the business of leadership was, if not easier, at least more straightforward.

Leaders made decisions based on the best information available to them at the time.

Those decisions were then communicated to those they led, who would in turn decide to either accept or reject them.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.That stone tablet model of leadership doesn’t cut it in 2024 and hasn’t for some time. Not in Parliament House, the C-suite, in businesses, classrooms or institutions.

It’s become a common refrain to lament a dearth of leadership. It’s a problem that exists at all levels of society, in every industry and facet of our communities, but is most visible in our political institutions.

Where are our Curtins and Hawkes for the 21st century?

The truth is it’s much more difficult to be a successful leader today than it was in the eras of Curtin, Hawke, or even Howard.

Part of that is to do with the rapid and irreversible democratisation of information. No longer do our leaders hold privileged access to much more information than those they lead. Now, we’re all awash with more knowledge than we know what to do with.

We’ve learnt that often, there exists a disconnect between power and competence. Those who wield the former don’t necessarily have the latter.

A revival of the information imbalance was partly responsible for the huge popularity bumps our leaders experienced during the pandemic. They had information we didn’t, but desperately wanted. Millions of us tuned into daily press conferences and we hung off their every word as they drip-fed us the information they believed we needed, while they withheld that which they thought we didn’t.

Paradoxically, the same factors that have caused our leadership drought mean we are more in need of strong, capable leadership than ever before.

Our world is riddled with conflict and confusion. We’ve become so interconnected that we have come out the other side more divided as we focus more on the things that separate us than that which connect us.

The sheen has worn off our institutions. The more we learn about them, the less we see them as noble, in a self-perpetuating cycle of erosion of trust.

In the broader context, we see a clash of civilisations playing out through conflicts in the Middle East.

Many aspects of our society today are almost unrecognisable when compared to a decade ago, let alone a generation or two.

We’re faced with huge moral questions, and questions about the direction we want our world and country to go.

We need leaders to help us make sense of it all. We need trusted figures we can look to provide guidance as we grapple with these serious issues.

That will require a new model of leadership.

It’s not enough for leaders to simply tell us what to think anymore. We need them to help us interpret the information we already have, to inspire, and to galvanise, as humanity moves into its next chapter.