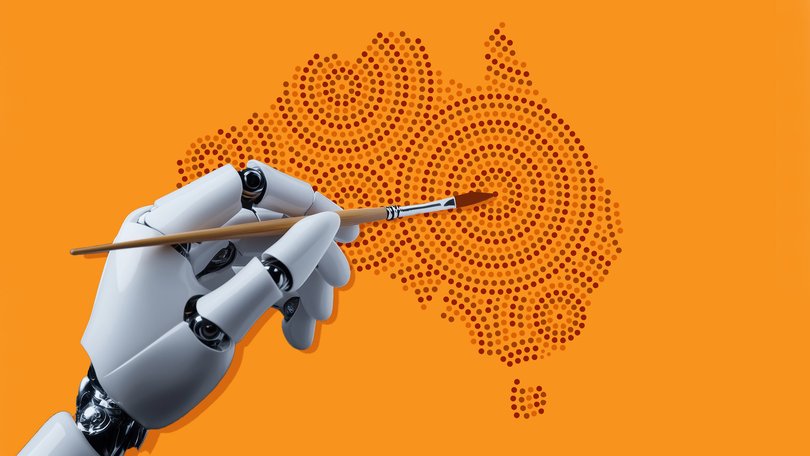

EMMA GARLETT: AI revolution poses great risk to First Nations creative work, threatens cultural sovereignty

EMMA GARLETT: Like classic colonialism, digital colonialism sees the rich and powerful exploit Indigenous people for profit.

If you’re not using artificial intelligence right now you’re already behind — that’s the view of those urging us to jump on the AI wave or risk missing out.

Among those advocating for a open-armed embrace of the AI revolution is the Productivity Commission. The commission last week released a paper which proposed creating a carve-out in Australia’s digital copyright laws which would allow tech companies free access to protected materials to train its AI models.

Australian creatives reacted with unanimous horror to this idea which would essentially turn over their lives’ work to AI which could then churn out soulless copies without putting a dollar in the pockets of the original creators.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The risks are especially great when it comes to the creative work of First Nations peoples.

This isn’t just a threat to our intellectual property, it’s a threat to our cultural sovereignty — the right to control and protect our own cultural heritage.

The beauty of Aboriginal art doesn’t just come from its visual appeal. We use art to tell our stories, to explain our world views and celebrate our culture.

Reducing this tradition to fodder for machine learning robs it of that sacred significance.

There’s a name for this: digital colonialism. Like classic colonialism, it’s about the rich and powerful exploiting Indigenous cultures and dispossessing people for profit.

Some tech evangelists argue the AI models need to have access to data from diverse cultures to avoid bias.

Earlier this year, software company Adobe came under fire when it was revealed that its AI models were producing wildly inaccurate stock images of “Indigenous Australians,” some painted in random markings with no cultural significance. Other images labelled as “Indigenous Australians” appeared to be mashed up with other people of other global cultures.

Clearly, this is a big problem.

But what does an “Indigenous Australian” look like anyway?

Australia is home to more than 250 different Indigenous language groups, all with their own culture and traditions. There can be no such thing as an accurate “stock image” of an Aboriginal person. Anything which claims to do so has only managed to homogenise rich and diverse cultures; a phenomenon the academics call “cultural flattening.”

That’s not to say that AI is all bad. It presents vast opportunities.

But we can’t let our eagerness to embrace this digital future rob us of our history and culture.

As in everything, free and informed consent is key. We need the right guardrails in place to ensure it’s done in a way that safeguards our cultural sovereignty and adds to, not destroys, our heritage.

Emma Garlett is a legal academic and Nylyaparli-Yamatji-Nyungar woman