JUSTIN LANGER: When does the t-shirt-look cross sporting tradition?

JUSTIN LANGER: The chequered arrival dates, casual attire and low-key lead up, reflects the modern game - probably modern times - at least in England and Australia.

Ben Stokes and his team arrived in Perth this week ready to take on the Australians in this highly-anticipated Ashes series.

Dressed in a T-shirt and a pair of casual pants, he strolled through the arrival hall with a couple of his English teammates.

Jofra Archer with his plaited hair and gold chain as thick as an arm, smiled and spoke to the cameras when he arrived two days earlier.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.His partner in crime Mark Wood, the relatively short, but very quick opening bowler, declared quietly that he and his team were here to win and that he was pumped for the series.

As is the way of today’s cricketing landscape, Stokes didn’t lead his full team through the airport.

Some will arrive from a white-ball series in New Zealand, others from England and others, depending on the schedule of their commitments, will get here when they are due to report for duty.

The chequered arrival dates, casual attire and low-key lead up, reflects the modern game -- probably modern times -- at least in England and Australia.

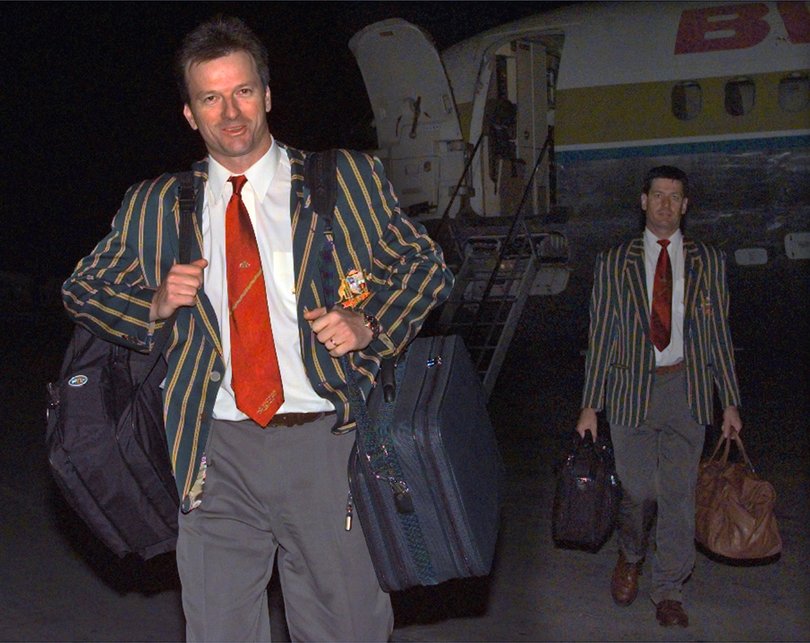

This is so different from past days. In the Bradman era, they boarded the boat in top hats and grey suits, sailing across the high seas for a six-month tour away from their families and home soil.

England, perceived by many Australians as the stiff upper lip of the Monarch and MCC, were the leaders in formality and pageantry. Arriving in shorts, tracksuit pants and T-shirts to represent their country, “is just not cricket old boy”.

It reminded me of a moment when I was checking into Darwin airport last year.

In front of me were a couple of Paralympians dressed in green and gold. Seeing them gave me goosebumps. Patriotic pride made me smile as they wheeled themselves through security on their way to the Paris Olympics. I couldn’t help but wish them luck. Their pleasure at representing our country was obvious, their new uniforms embodying a suit of armour, carrying them to their life goal of an Olympic challenge.

Today, perhaps due to the 12-month schedules of an international cricketer, arrivals tend to meld into one and it is not unusual to see our stars arriving in whatever feels the most comfortable.

For some observers, the lack of pomp will be met with shock and horror, but to the current players it is just a new way of doing business. It’s also a sign of the trend of individualism over team, that has become so prevalent in sports in America and other countries.

Changing times aside, when the players are standing in their white clothes belting out their respective national anthems, coat of arms bursting from their chest, that will be the only uniform that really matters. Baggy greens and blues will on display and the same pride I have felt and seen at airports in the past, will be equally as strong come game day.

Cricket is a game that is steeped in tradition but one that has also seen its share of changes, that have either been embraced, or outlawed, depending on those that are in charge at that time.

It is sometimes difficult to know which innovations or styles will stay or go, but there are some hints when reflecting on historic examples.

When Graham Yallop used a motorcycle helmet for the first time in a Test match against the fearsome West Indies bowling attack in 1978, he was booed by the crowd. The laws of cricket didn’t prevent the use of helmets, but challenging the status quo was frowned upon at the time.

Helmets are now widespread, and in most cases compulsory in today’s game. For helmet manufacturers this was good news and quickly the competition to take market share _ by making stronger, lighter and safer cricket helmets - made economic sense. Yallop’s boldness opened a new market.

Dean Jones was the first to wear sunglasses on the field. “Who is this clown?” was the call.

Deano didn’t care; he was interested in comfort, safety and performance. A new market was born and there are few players today who don’t wear Oakley sunglasses during a match.

Dennis Lillee’s carried an aluminium bat onto the field in 1979. Again, there was no law against it. But the different sound of the ball hitting the bat was too much for the England team and they complained that the bat damaged the ball.

Dennis responded by throwing his new toy to the boundary and it didn’t take long for the lawmakers at the MCC to change the rules of cricket to only allow wooden cricket bats. What worked in baseball and tennis was outlawed in cricket.

In today’s market - where English willow is running dry and pushing bat prices to the heavens - you can only wonder if there may be a re-think at some stage.

The MCC who once banned Dennis’s innovation is now scampering to find solutions to the worrying trend of astronomical bat prices that could turn cricket into an elitist sport for those with money.

Ricky Ponting’s bat sponsor (and mine), Kookaburra Sports, tried to be innovative with cricket bats in the early 2000s by introducing carbon fibre stickers onto the back of the bats to strengthen them.

This innovation was ultimately deemed by cricket’s administrators as being unlawful and had to be withdrawn for professional use.

Parents today, who are buying their daughters or sons a new bat for Christmas, might sign petitions for such invention to be re-introduced.

Innovations that tend to enhance the fan experience of sport tend to be well supported by governing bodies. Examples in cricket such as “Hawkeye”, “Stump Cam”, “Zing bails” and the “Pingmaster” come to mind.

However, when the innovations are deemed to affect the outcome of the game itself, that is where governing bodies tend to become wary. Much talk prevails about the change in cricket bats, tennis racquets, golf clubs today, but like uniforms, it is not the equipment that really matters.

Rather, it is who is holding the tools, or wearing the unform that really matters.

Throughout history, great leaps forward in sport have often come from those that challenge the status quo. In some sports, the rules are simple (or vague) enough that allow innovation to flourish in attempts to get an edge over the opposition.

However, it is often common that when innovation causes an unfair gap between the haves and the have-nots, then often the rules are changed that limit the effectiveness of the innovation, so that the fair playing field can be levelled again.

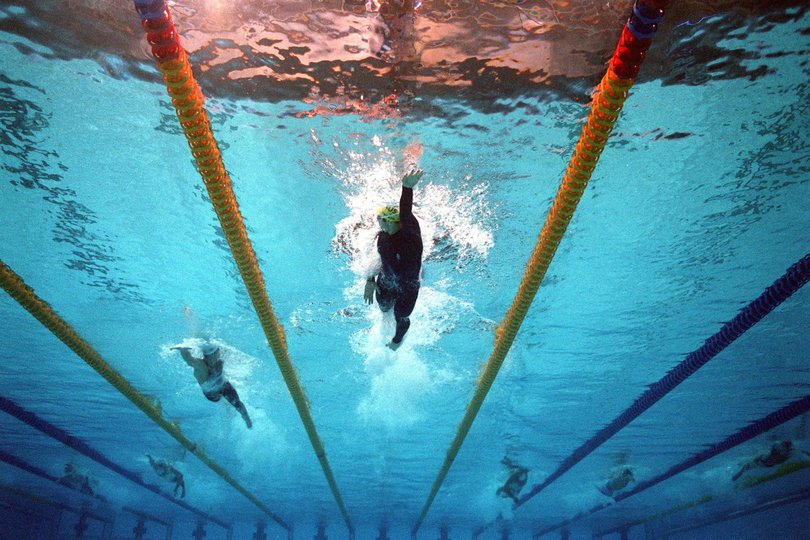

A famous example in swimming was the use of “sharkskin” swimsuits when world records were being broken at regular intervals. Use of the suits were eventually banned in international competitions because those swimmers who could not afford the high-tech swim wear were disadvantaged.

Swimwear companies could still market their speed enhancing suits to the public, but their free marketing exposure of their technology at elite events was stopped by the governing body of swimming.

Cathy Freeman’s sprint suit, the iconic Nike Swift Suit, was an aerodynamic, full-body skinsuit she wore when winning the gold medal in the 400m sprint at the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

Engineered to reduce drag and increase speed in short distance running events, the green, gold, and silver suit featured a hood and was designed to minimize aerodynamic drag. Now one of the most famous outfits in Australian sporting history, I have never seen it worn again, but it still lies as a symbol of the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

Fancy and effective as the swimming and running suits may be, it was the athletes inside them that truly captured our hearts.

Those who tut-tut the lack of formality or the rise of T20 cricket these days are absolutely allowed their opinion, but when it comes to day one of the Ashes, it won’t be the clothes on display or the bigger cricket bats, it will be the steel, skill and temperament of those wearing them that really matters.