KATE EMERY: We need to do more to combat Australia‘s silent epidemic — loneliness

KATE EMERY: Having no mates isn’t just a bummer, it’s linked to a swag of health problems.

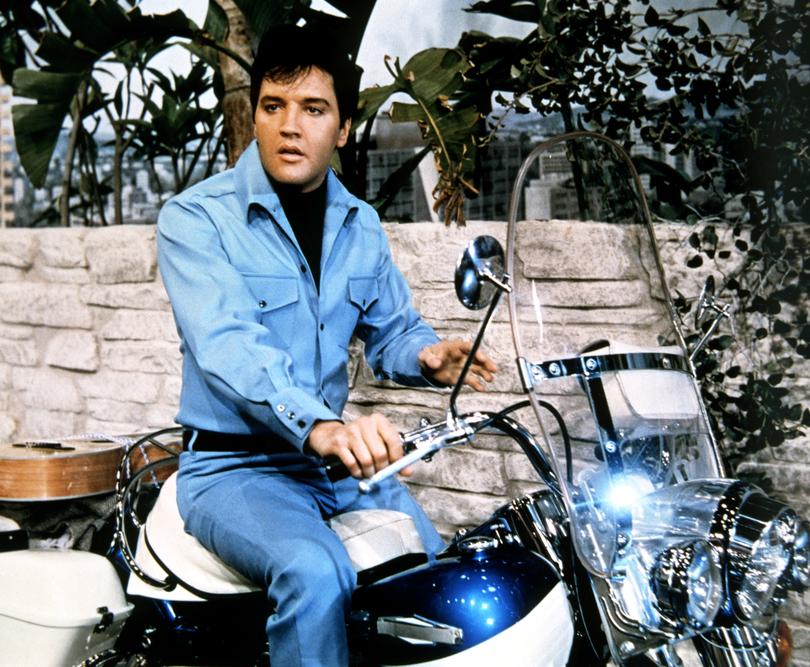

It’s been nearly 70 years since Elvis Presley wanted to know: are you lonesome tonight?

Sure, American composers Lou Handman and Roy Turk wrote and sang it first but, lacking Presley’s bone structure and marketing budget, they have since faded into obscurity.

Ask the average person who they think is lonely and there’s a good chance they’ll pick someone old enough to have heard Presley ask the question in person.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.That old fella whose ear hair is threatening to choke his hearing aid. The little old lady who sits in her garden every morning. The nursing home residents mark the days by the lunch menu (fish and chip Tuesday is when the smart relatives drop by for a visit).

Old people are indeed at risk of social isolation and loneliness. (If you’re reading this sentence and thinking about your own gran, finish reading the article then go visit her. Tell her I said hi.).

But young people can be even more lonely. They’re definitely lonelier than you think. And it’s getting worse.

Twenty years ago the biggest cohort of lonely Australians were those over 65.

But, while older Australians are actually less likely to feel lonely now than they did at the turn of the century, young people are more likely to do so.

The most recent Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey of Australian loneliness found the country’s oldest residents had the lowest rates of loneliness in the country. Meanwhile, the proportion of lonely Australians between the ages of 15 and 24 rose from 19 per cent in 2001 to 25 per cent in 2021: the only age bracket to see loneliness get worse in that 20 year period.

A just-released report into loneliness and social isolation in the Australian Capital Territory also found that young people were at particular risk of loneliness, even more so if they identified as LGBTQI.

Social media is part of the problem. The 1990s weren’t halcyon days for teens but at least we didn’t have to spend our weekends staring at photos of more popular people attending parties we weren’t invited to. And bullies had to confine their favourite leisure activity to school hours.

The working from home trend also deserves some blame — and not just for convincing us that elasticated pants are basically smart-casual, actually.

Turning up to work every day has downsides: the need to shower first, productivity-sucking small talk and paying $11 for a deeply average sandwich, then eating a giant slice of crap cake just because some colleague you’ve never met left it in the kitchen.

But being thrown into proximity with other people every day opens the door to workplace friendships, romances and the opportunity to bond over the soul-crushing tedium that is, well, work. Also, being forced to take a shower every day probably isn’t a bad idea.

That ACT report made a lot of recommendations, including more spaces for young people and making public sports facilities free to access. It also proposed an ACT minister for loneliness.

Why stop there? Why not a Federal minister for loneliness, tasked with tackling what is not just a thing for us all to feel bad about but a genuine public health issue. Lonely people, you see, aren’t just a bummer: they’re much more likely to have dementia, heart problems and a whole swag of other health problems.

In 2018 the UK created a Minister for Loneliness in what it said was a world first. You’ll be stunned to hear that a country that’s enjoyed five different prime ministers since then hasn’t quite got around to solving the loneliness epidemic.

Forgive my scepticism but Australia doesn’t really need a minister for loneliness, not because it’s not a serious problem but because we already know what we need to do and a new business card isn’t going to change that.

Australia’s National Preventative Health Strategy 2021-2030 and its National Primary Health Care 10-Year Plan 2022-2032 both acknowledge the reality of loneliness as a serious public health concern.

They’re also chockful of ideas for what the Government might do to help, including more public open space, green space, programs to get people physically active and support for Australians from culturally diverse backgrounds to be part of the community.

The loneliness epidemic also has to be part of the conversation as the Federal Government pushes forward with its proposed social media ban for kids.

Because, while social media can absolutely be part of the problem, it can also be part of the solution. Young people who feel socially isolated can find solace, friendship and their tribe online.

Lonely people are all around us — some of you are reading this column right now — and they deserve more than sympathy. They deserve action places to go and avenues to make the human connections that make life worth living.

This column started with a question sung by one musical great so let’s end with a different question sung by another.

All the lonely people, where do they all belong?