KATE WAGNER: When did it become normal to gleefully participate in the ruin of others’ lives?

Far be it from me to defend a powerful man who is locking lips with his employee on camera — almost certainly a violation of company policy, if not labour laws.

But when I heard about the viral exposure of Astronomer CEO Andy Byron and his head of human resources, Kristin Cabot, at a Coldplay concert, my instant reaction wasn’t “These people deserved their comeuppance”.

It was: “Why is the ruining of two strangers’ lives so normalised?” To me, Mr Byron and Ms Cabot’s moment of shame is more than just a scandal (and subsequent meme) — it’s an edge case in what should become a broader debate about the harmful yet shockingly commonplace practices that are a scourge upon the way we as a society behave online.

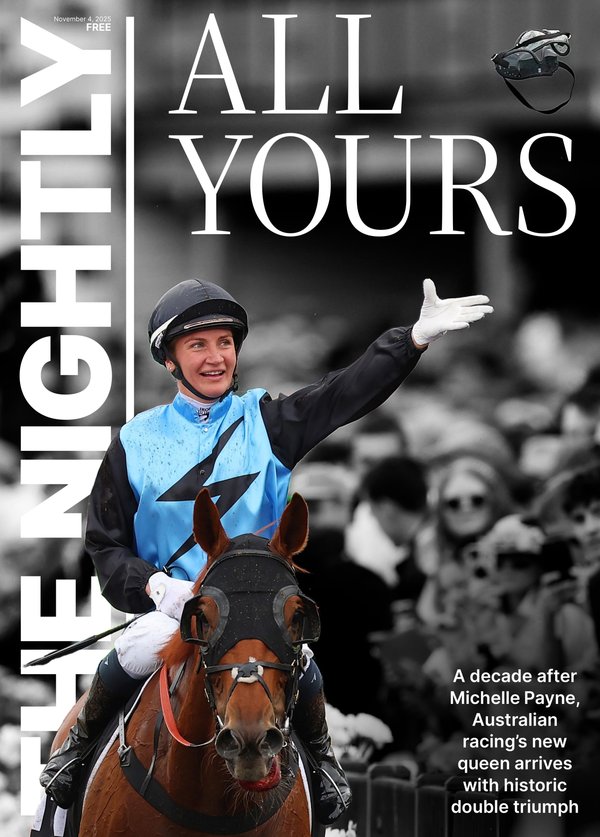

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The internet has become the surveillance state we were once warned about by sci-fi movies — except rather than some spooky Skynet, it is we who are surveilling one another.

Think about how often you see a viral photo of a stranger in the supermarket or on the subway that has been posted online without that person’s consent. Or perhaps a screenshot of a dating profile or private conversation being shared for either amusement or validation. “Is my roommate being the crazy one?” “Isn’t this random guy on Hinge soooo unfunny?”

It has become shockingly normal for everyday people to act like vigilantes who feel entitled to punish or police the (often benign) actions of others. The problem is not that Mr Byron shouldn’t be reprimanded for his actions, especially as an employer, but that the panopticon we’ve turned on him is one we are all too willing to use on others, with just as much glee.

As soon as the video appeared online, thousands of people took it upon themselves to identify these two individuals who appeared to experience a moment of unexpected embarrassment.

No one knew going into this that the couple would turn out to be a CEO and his employee. They could have been anyone, ordinary people, and they still would’ve been doxed. What excuse is there for the doxers? To show that one is against infidelity?

Cheating, though painful to the parties involved, is a pretty routine way people hurt each other. It’s not a crime, nor is “cheater” a kind of immutable status one must be branded with. Couples often break up, but they also can and do reconcile.

Exposing strangers — or your ex — to the unbridled judgment of the internet (especially popular via short-form video) is an unacceptable escalation to something potentially life-ruining, all for entertainment. Those who do it with some pretence of serving justice seek to make cheating so stigmatised that we, the inmates of our collective internet prison, police our own behaviour.

When vindictive exes post revenge porn of their former partners, or creeps make lewd deepfakes of celebrities, we rightly denounce this behaviour as invasive and cruel. Yet there is not much distance between outright crimes and the still-harmful exposure we’ve come to accept when the content isn’t explicit in nature.

This kind of collective policing is neither healthy nor appropriate. All it will do is drive people away from both intimacy and public life out of fear. Why dare to wear that outfit on the subway? Why try to be funny on Hinge and risk having it go viral? Why go on dating apps at all, since one popular genre of short-form video consists of scrolling through people’s profiles on camera?

The fear of being filmed and photographed is increasingly seeping into what should be some of our happiest experiences. The rapper Tyler, the Creator recently held a no-phones album release party and saw a marked difference in energy and verve.

Afterwards, he posted on Instagram: “I asked some friends why they don’t dance in public and some said because of the fear of being filmed. I thought damn, a natural form of expression and a certain connection they have with music is now a ghost. It made me wonder how much of our human spirit got killed because of the fear of being a meme.”

How do we get ourselves out of this mess? Even though public and private are blurred in online life, we need a serious culture shift away from the entitlement we claim to other people’s lives and bodies. We have to begin by fighting this urge in our own lives. If someone hurts us, the answer is not to expose them to our audience as punishment or a form of self-validation.

We need to stop being complicit in mass surveillance by pausing to think before we share that funny screenshot, juicy gossip or Insta-viral subway outfit. This is especially true of any content whose purpose is to shame and expose what are often benign personal transgressions.

To shift away from surveillance and punishment and back to freedom of self, movement and expression, we need to ask ourselves: What if it happened to me? Because it can — it always can. We’re already living in fear of ending up as someone else’s internet bit. The way to protect ourselves is to protect others, too.