Mark Riley: Does Prime Minister Anthony Albanese have the courage to be a true friend to China?

Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations wasn’t just the best speech he delivered in office, it was one of the best by any prime minister since federation.

Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations wasn’t just the best speech he delivered in office, it was one of the best by any prime minister since federation.

But another of his speeches, although much less celebrated, is equally worthy of being placed in that same category.

It is one he gave in Mandarin to students at Peking University during an official visit to China in 2008.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

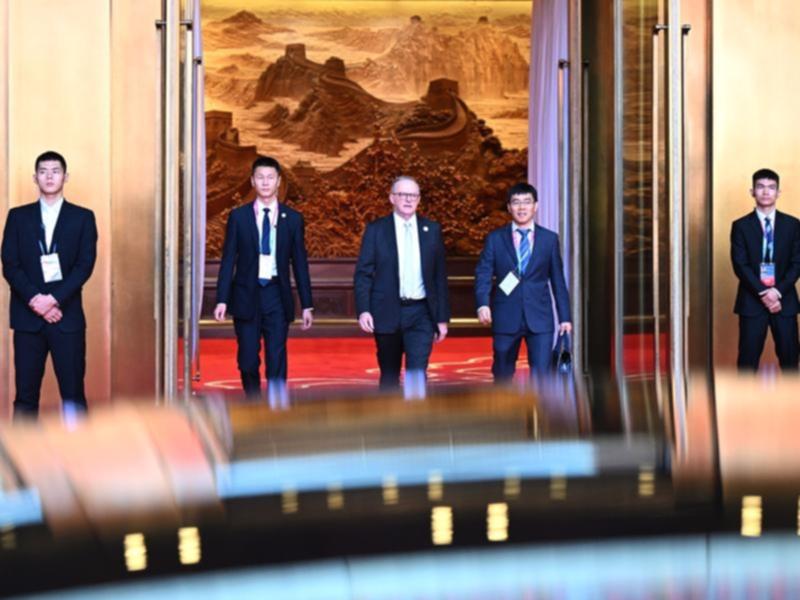

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.And it is one that Anthony Albanese should now channel as he heads to Shanghai and Beijing this weekend.

In the heart of China’s most exalted seat of learning, one that has produced its greatest thinkers, writers and agents for change, Rudd laid out a new blueprint for the bilateral rules of political, economic and strategic engagement.

The Chinese language has many words to describe a friend. But the one Rudd chose to define the relationship Australia should strike with Beijing caused ructions among the Chinese leadership and its national media.

Rudd said Australia should be a “zhengyou”.

It is an ancient term defining a true friend who dares to disagree.

China had few of those then and has fewer, if any, now.

It was just one word, but it was a powerful word. Rudd was saying that Australia wanted a productive and prosperous relationship with China, but it wasn’t going to do that with its wallet open and its mouth shut.

It was quite a departure from the Howard way, which had relied more heavily on nuance and pragmatism.

John Howard would acknowledge that China and Australia had different views on matters of security and human rights but then say he preferred to concentrate on the things we had in common rather than those that divided us.

“We haven’t come to hector and lecture and moralise,” he told the travelling media on a 1997 trip to Beijing.

Anthony Albanese shouldn’t do that either as he now attempts to set new ground rules for re-engagement with the country that is both our largest trading partner and our biggest security risk.

But he needs to be as frank and fearless as the diplomatic parameters for his official meeting with President Xi Jinping will allow.

His visit will mark 50 years since Gough Whitlam went to Beijing as prime minister, having established official diplomatic relations with China a year earlier.

The Chinese tradition is rich in symbolic gestures and this is an important one.

But striking a balance between what Australia wants to achieve and the values and principles it must never concede is critical.

The timing for Albanese is challenging, coming so soon after his most potent critique of President Xi’s ideological objectives in Washington last week.

Flanked by US Vice-President Kamala Harris and Secretary of State Antony Blinken, the Australian Prime Minister essentially accused Xi of attempting to upend the current world order and impose his country’s hegemonic influence across the Indo-Pacific.

“China has been explicit: it does not see itself as a status quo power,” Albanese said.

“It seeks a region and a world that is much more accommodating of its values and interests.”

President Joe Biden had cautioned a day earlier that the West should “trust but verify” all undertakings from Beijing.

ASIO and its intelligence partners at the recent Five Eyes meeting also warned that China is engaging in industrial scale intellectual property theft and destructive cyber warfare attacks on its trading partners.

Then, there are the rather large matters of China’s support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its unwillingness to call out Hamas for its despicable attacks on Israeli civilians.

China has been clearing the way for Albanese’s visit, removing its trade restrictions on our exports and finally releasing Australian journalist Cheng Lei.

President Xi has also spoken of a bilateral relationship that should be “cherished”.

But Australian writer and blogger Yang Hengjun remains imprisoned in China and Australian wine exports continue to suffer punitive restrictions.

Albanese says he wants an “open and honest relationship” with China, one “with no surprises”.

No doubt in his conversations last week with our now Ambassador to the US, Albanese was advised by Kevin Rudd that doing that would require real political bravery.

The potential dividends of a good relationship with China are huge, but the cost of not ensuring it’s also an open and honest relationship could be dire.

Anthony Albanese needs to have the gumption to insist Australia finally become a true “zhengyou”.