MICHAEL USHER: Thank you to the caretakers who protect the graves of our Anzac veterans laid to rest overseas

MICHAEL USHER: Thousands of young Australians lie in foreign soil. An army of caretakers dedicate themselves to protecting their rest.

On the edge of the Libyan desert, where pale, dirty sand meets the soft coastal edge of the Mediterranean Sea, lies an immaculately curated corner of Australia.

In all this unremarkable landscape, a very special piece of Australia is gently groomed and guarded, every day, all year round for the past 83 years.

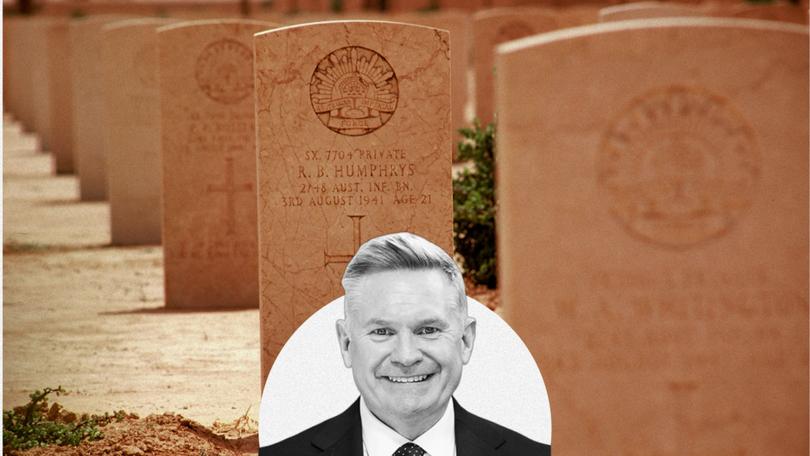

It is the Tobruk War Cemetery. There are 559 Australians buried there, and perhaps a few more as some of the headstones mark the graves of the unknown.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.These soldiers were the legendary Rats of Tobruk who fought and died in this northern part of Africa, right near the Egyptian border during the brutal eight-month siege of 1941.

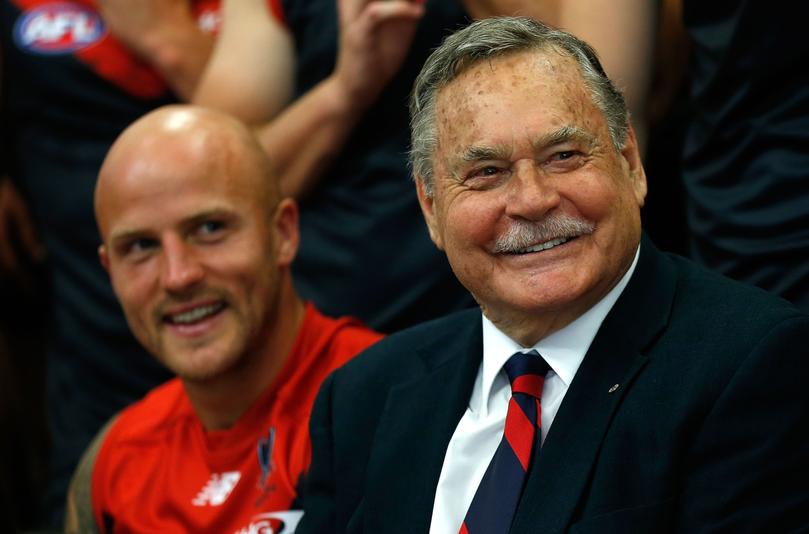

I visited there with the late AFL great Ron Barassi.

His father Ron Snr was one of the Australian soldiers who signed up for King and Country at the height of his footy career, to fight a war a long way from the Melbourne footy grounds where he was a champion. Ron Snr was cut down in battle on July 30, 1941, during that siege.

He was only 27.

When I travelled with Ron Jnr — strange to call him Junior given the giant he was — Libya was a wreck of a country in the wake of the Arab Spring and the downfall of the Ghaddafi regime. It was a risky journey, but a pilgrimage Ron had to make. He knew it was the last time he’d visit his father’s grave, and sadly it was.

Ron draped a Melbourne footy club scarf over his father’s headstone and simply wept.

It was a chilly dawn. The sun peeked over the low wall of the Tobruk Cemetery and soft, warm streams of light caused the tears on Ron’s falling freely on Ron’s cheeks to glisten.

I stood back a few paces while Ron quietly let his thoughts roll through the emotions of a boy losing a father. In the same moment, a five-year-old who never got to know his dad, and a footy hero honouring a war hero.

It was so overwhelmingly emotional, powerful, and respectfully quiet.

But here’s what also struck me about that moment, and I’ve been fortunate to experience this a few times before. In this quiet corner of a then chaotic Libya, reflecting on what must been a godforsaken hell hole during that marathon siege of 1941, it was simply beautiful.

Not by any classic definition at all, but beautiful, nonetheless. Some war cemeteries are oil paintings of manicured green lawns, perfect hedging, and symbolic, seasonal flower beds.

Not here, just not possible on the edge of a desert and blasted by a salty sea. But it was immaculate.

The dirt was swept daily in neat patterns. The rows of symmetrical headstones dust free, and the main monument is cleaned to reflect the best light.

And this doesn’t happen by accident. There at the gates of the Tobruk War Cemetery was an elderly Libyan gentleman who was the keeper of the keys, and the keeper of the grounds. Through all of Libya’s strife, this man had kept our scared site spotless.

For every stiff desert breeze that threw its sticks and stones and sand on the graves of our boys, he was there to sweep it clean.

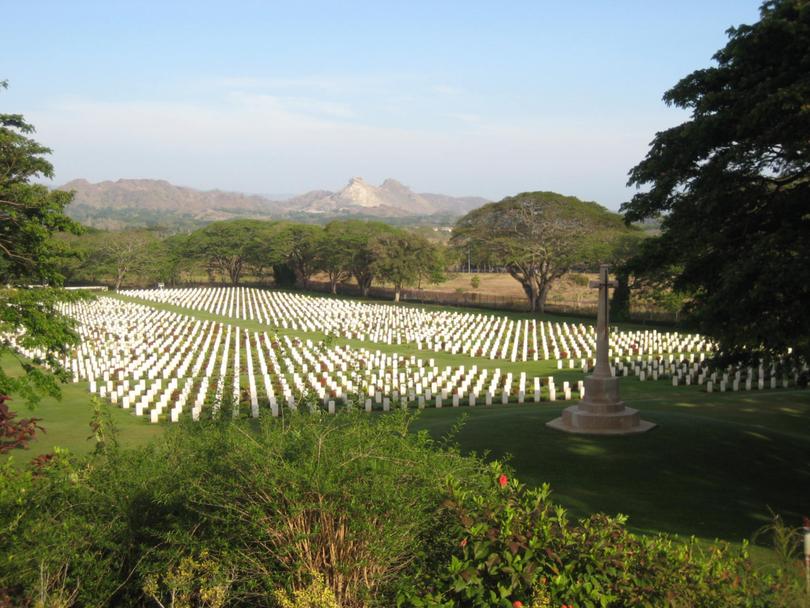

And this is where we should all find a point of national pride. I know I’ve felt it overwhelmingly when I’ve been beyond grateful to visit Australia’s war cemeteries throughout Europe, northern Africa, Turkey and Papua New Guinea. The Office of Australian War Graves with the Department of Veteran Affairs and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission make sure the grounds of these hallowed sites are always maintained and never neglected.

Across the globe, there are generations within local families in those countries, who’ve been tasked with making sure the resting places of Australians who served and sacrificed are always neat, clean and honoured.

It is an incredible job that is rarely recognised. When we see the Prime Minister stand solemnly at the Isurava memorial in Papua New Guinea tomorrow, remember those granite pillars weren’t just polished and prettied for a visiting leader.

They’re always kept that way.

Thanks to good people in those government departments whose passion is for preserving the memory of losses in battle, not bureaucracy. They never forget and mostly go unsung between key memorial dates. And also, to the local army of caretakers employed to preserve our sites, even in the long spells between visiting dignitaries.

And for some those visits are rare, because what’s more important are the unannounced visitors.

The Australians, young and old, who post-COVID, are flocking back to our war cemeteries overseas to search and claim family history. I’ve watched the tangible and tender moments when these Australians kneel at the headstone of a young man in their past who never came home.

They run their fingers along the chiselled or engraved family name that they now carry, as if by braille and touch to connect to the young soldier, to learn his fate and feelings in those terrible conflicts. Or through fingertips, to send love.

It is just so deeply emotional, and it happens almost every day in these cemeteries. On the clifftop of Gallipoli, and in lesser-known cemeteries like the three sites on the small Greek island of Lemnos where 148 Australians rest.

And these family moments of reflection and honour are thanks to a wonderful preservation of our Anzac history.

Every day, the dedicated tend to these graves, pluck the weeds, sweep them clean, and make sure names are cleared of mother nature’s wear and tear.

Thank goodness for the good caretaker soldiers who keep our men and women at peace a long way from home.