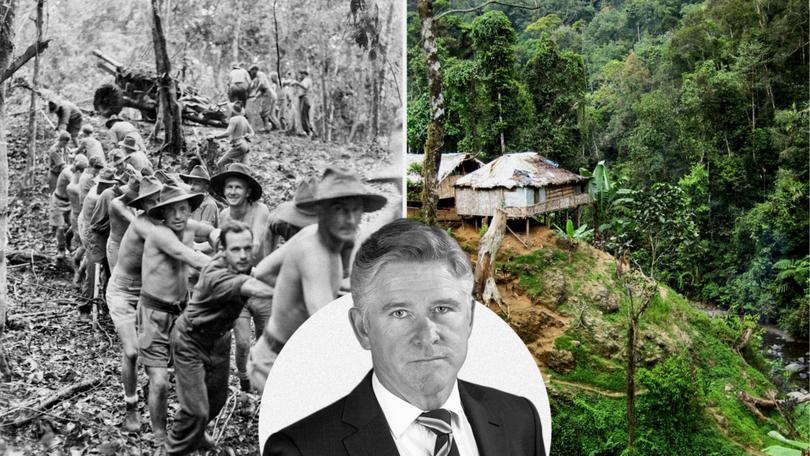

MARK RILEY: Albo’s Kokoda Track journey will see a new generation of Australian and PNG leaders walk together

MARK RILEY: Anthony Albanese’s Kokoda Track journey will see a new generation of Australian and PNG leaders walk shoulder to shoulder.

Like generations of Australians, Anthony Albanese has long harboured a desire to walk the Kokoda Track.

It’s something he’s considered doing since his days as an intrepid backpacker.

Trekking Kokoda stands alongside the pilgrimage to Gallipoli as a right of passage that connects Australia’s present with a defining chapter of its past.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Climbing those brutal jungle trails allows ordinary Australians to experience some of the extraordinary challenges their young forebears confronted during the seminal PNG campaigns of World War II.

It is a desire Albanese has mentioned several times to his PNG counterpart, James Marape, in their many forum meetings and reciprocal bilateral visits.

But it was at a dinner at the Lodge in February, the night before Marape delivered his impressive speech to the Parliament, that Albanese made a decision.

It was time for him to stop talking about walking Kokoda and get out and do it.

And he would do it to coincide with Anzac Day so he could honour the memory of the Aussie diggers at a dawn service on one of the storied battlefields.

Several Australian prime ministers have been to Kokoda village for Anzac Day and many MPs have walked the track before.

But Albanese is the first serving prime minister to do it.

What surprised him was Marape’s enthusiastic response.

“Good,” the PNG leader said. “I will come, too.”

And so a new generation of Australian and New Guinean leaders are walking shoulder to shoulder across the Owen Stanley Range today just as the diggers and Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels did between July and August 1942.

As one of the fortunate five journalists invited to join the prime ministers, I can vouch for how tough and unforgiving the steep mountain paths are for those who choose to challenge them.

But walking these trails with all the modern equipment and ample supplies we have with us is a far cry from the fearsome challenge the diggers faced.

The fighting along Kokoda was some of the most brutal and most desperate of any WWII campaign.

The Australian soldiers not only battled a well-drilled, well-armed and fanatically committed Japanese enemy but the elements themselves.

Around 630 Australians died but more than 4000 fell desperately ill from dysentery, malaria and other jungle illnesses in the most brutal and inhospitable of settings.

They were fighting, as Paul Keating put it on his visit to Kokoda, not for the glory of war but for humanity.

The Japanese were trying to take control of the track to launch an assault on Port Moresby, which they’d planned to use as a base to target Australia’s northern airbases.

There is much conjecture in military and historical circles about whether the Japanese ever really planned to “invade” Australia.

Their short-term objective was undeniably to cut Australia off from its main Pacific ally, the US, by degrading its airforce and isolating its navy.

Perhaps the longer-term plan was to establish some sort of post-war occupation of Australia, but theories that the Kokoda campaign was planned as a forerunner to a mass invasion have been debunked over the years by leading historians and the military establishment.

For as much as the diggers knew, though, they were fighting for our very sovereignty.

Their aim was to force the Japanese back from any staging point above Port Moresby and they did.

It is a story that is now deeply etched in the pantheon of Australian heroism.

But it was an imperfect campaign.

Australian commanders made many mistakes, including one disastrous attack that set Australian militia against AIF soldiers across the track, inflicting heavy casualties, each suspecting the others were Japanese.

But that is war.

And we should be eternally grateful to those young soldiers who fought to maintain control of the Kokoda Track and turn the Japanese around.

In a large way, their courage and gallantry ensured that Australia remained Australian.

To now walk some way in their footsteps up these steep and muddy mountains is more than an experience. It is a privilege.