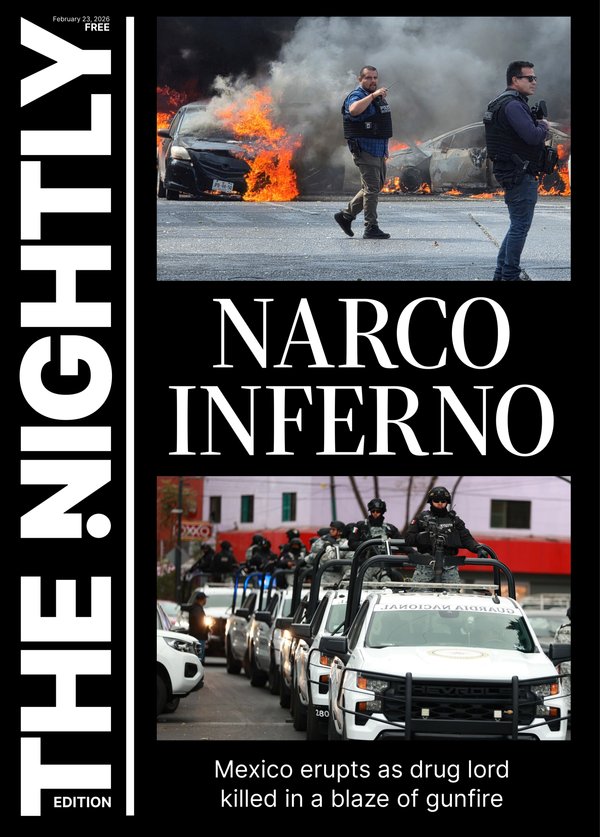

MICHELLE GRATTAN: A repeat of Whitlam’s 1975 sacking is unlikely but not impossible

MICHELLE GRATTAN: Could we see a repeat of Gough Whitlam’s 1975 sacking? As many have pointed out, the main characters are missing.

In his just-released memoir, historian and former diplomat Lachlan Strahan recalls being picked up from his Melbourne primary school by a neighbour on November 11 1975, the day Gough Whitlam was sacked as prime minister. His politically active mother “was so upset she didn’t trust herself behind the wheel”.

Journalist Margo Kingston was a teenager and not political at the time. She remembers going to bed that night, pulling the covers over her head and listening on the radio. The next day, she organised a march around her Brisbane school.

Fifty years on, the dismissal is one of those “memory moments” for many Australians who were adults or even children when it happened.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.This was a life-changing day for many who worked in Canberra’s Parliament House. For Labor politicians and staffers, it bordered on bereavement. Excitement and elation fired up the other side of politics. Those of us in the parliamentary press gallery knew we had front-row tickets for the biggest show in our federation’s history.

The dismissal didn’t come out of nowhere. It followed extraordinarily tense weeks of political manoeuvring, after the opposition, led by Malcolm Fraser, blocked the budget in the Senate in mid-October, and Whitlam refused to call an election.

On the morning of Remembrance Day, Whitlam prepared to ask governor-general Sir John Kerr for an election. Not a general election, but an election for half the Senate — a course that would have little or no prospect of solving the crisis.

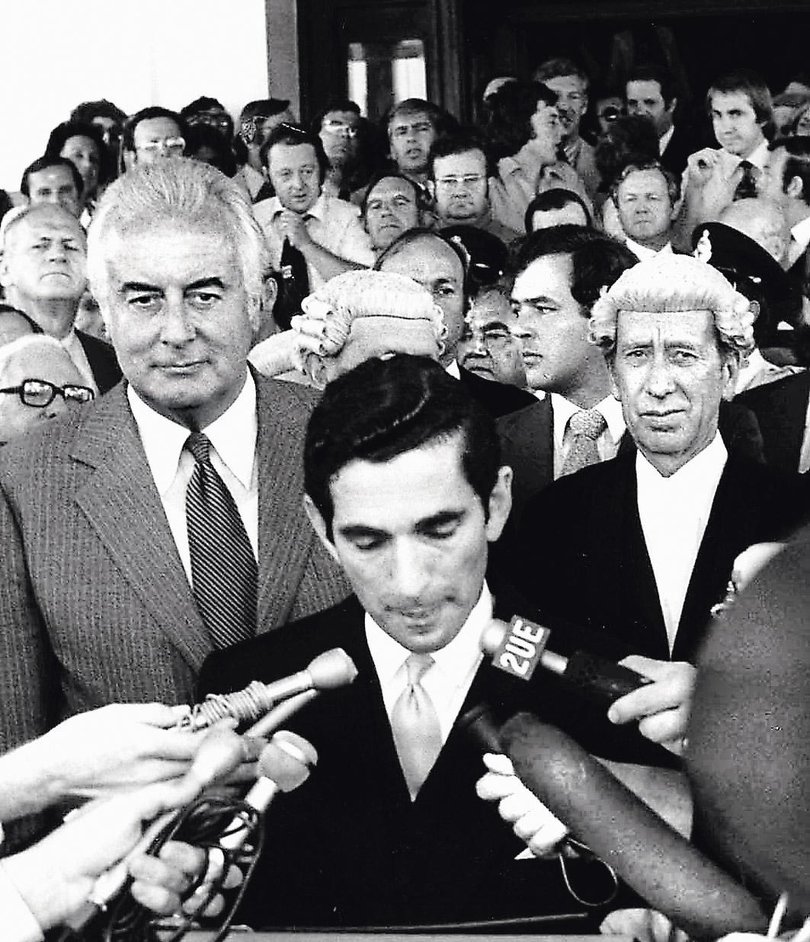

But Whitlam had fatally misjudged the man he’d appointed governor-general. Kerr was already readying himself to dismiss the prime minister. He gave Whitlam his marching orders at Government House at 1 pm.

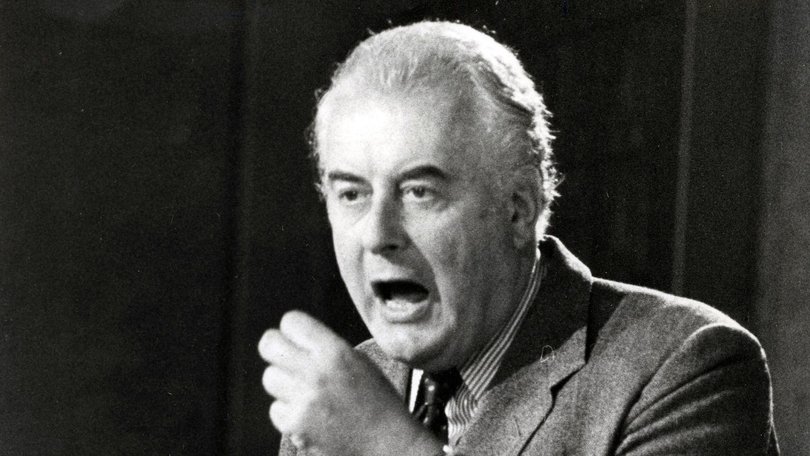

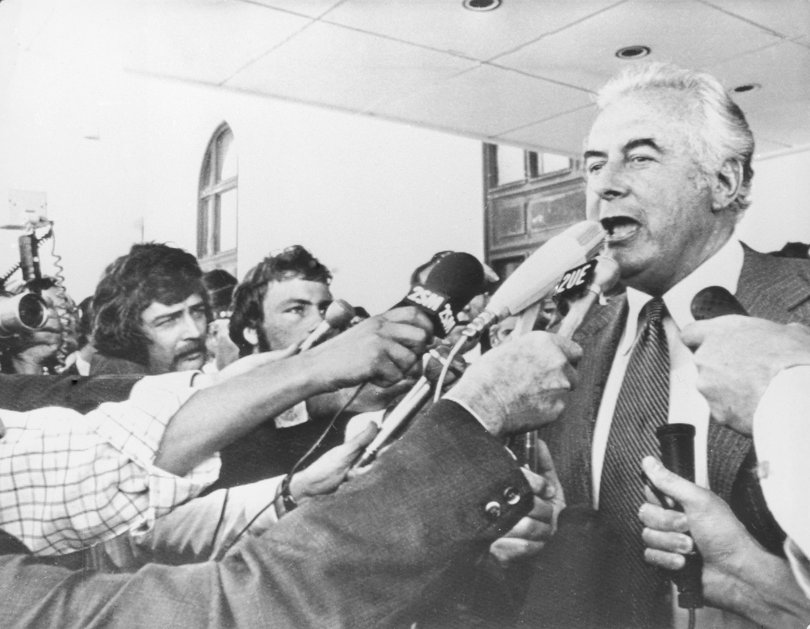

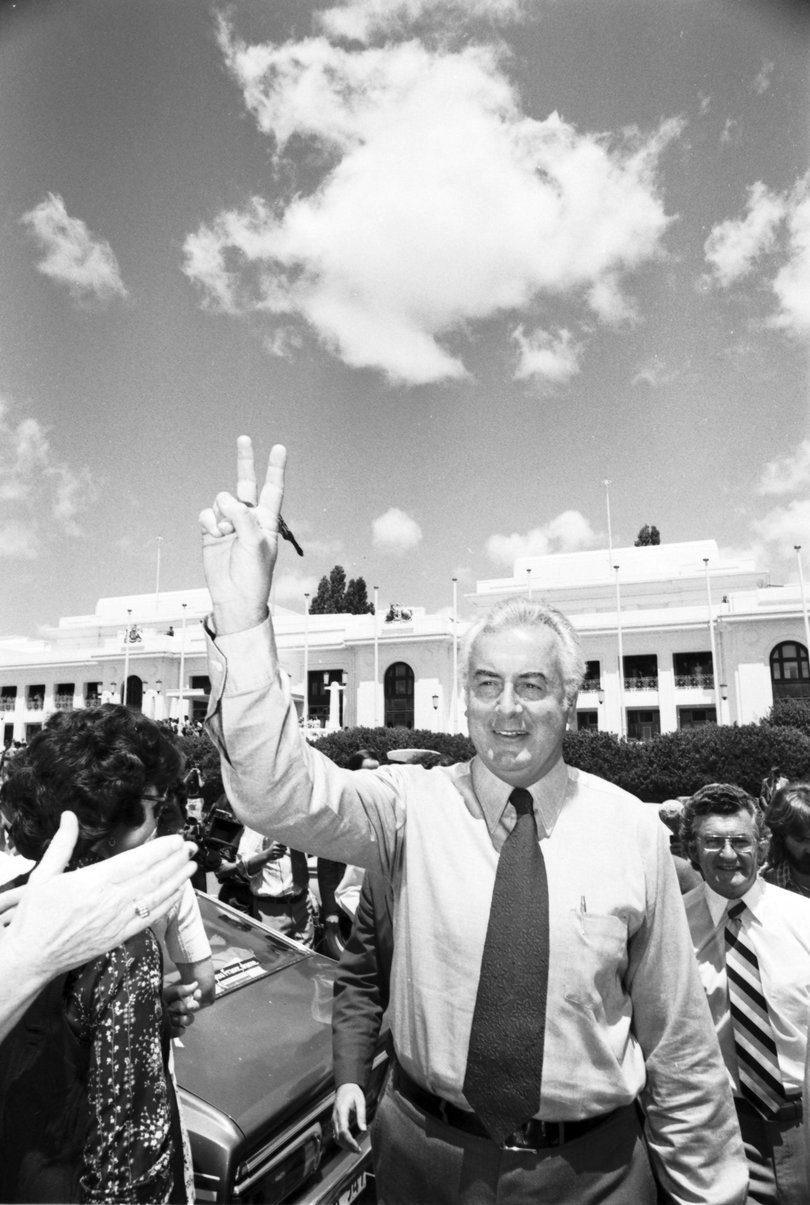

That afternoon Whitlam, eyes flashing, deployed his unforgettable rhetoric on the Parliament steps. “Well may we say God Save the Queen, because nothing will save the governor-general”, he told the crowd, denouncing Fraser as “Kerr’s cur”.

Whitlam urged the crowd to “maintain your rage and enthusiasm through the (election) campaign” (an exhortation later taken to apply more generally). In the subsequent weeks, Labor supporters did so. I spent much of the campaign in the media contingent travelling with Whitlam: it felt like there was momentum for him.

The feeling was, of course, totally deceptive, in terms of the election’s outcome. As the opinion polls had shown before the sacking the voters, who had enthusiastically embraced the “It’s Time” Whitlam slogan and promise in 1972, had lost faith in Labor three years on.

Whitlam’s had been an enormously consequential, reforming government. It transformed Australia, with landmark changes in health, education, welfare and social policy.

It inspired the baby boomers. But it had been shambolic administratively, disorganised and corner-cutting. Some ministers had run riot. Whitlam was charismatic and visionary, but he lacked one essential prime ministerial quality: the ability to run a well-disciplined team. Then, as things started to go wrong, the government’s media enemies became feral.

A combination of how he ran his government and how that government ended made Whitlam in later years both an example to be avoided by subsequent Labor governments and a martyr in Labor’s story.

Despite his huge electoral mandate, Fraser’s road to power in part defined how he was seen as prime minister, especially in his early years. Some believed it made him more cautious; many in the media viewed him in more black-and-white terms than the reality.

Kerr paid a high price. Leaving aside the partisans, many observers condemned his actions, particularly on two grounds: that he had intervened prematurely and, most damning, that he had deceived Whitlam, rather than warning him he’d be dismissed if he continued to hold out.

Kerr’s fear (probably reasonably-based) that if he alerted him, Whitlam would ask Buckingham Palace to remove him, didn’t convince critics. He was branded as dishonourable and cowardly.

Fraser took care in appointing the next governor-general. He chose a widely respected, unifying figure in Zelman Cowen.

The dismissal left fractures in our politics for years and its legacies forever. But Labor recovered faster than many had expected (despite Whitlam being trounced again in 1977). It was back in office in under a decade.

Our constitutional arrangements remained basically the same, with the governor-general retaining the reserve powers to dismiss a government.

There was one change, however: Fraser ran a successful referendum to prevent recalcitrant State governments from stacking the Senate by appointing rogue candidates to fill Upper House vacancies. That loophole had enabled the blocking of supply. The dismissal did not push Australia towards a republic.

Could we see a repeat? Who knows what may have happened by the time we reach the 100th anniversary. But as far ahead as we can see, the events of 1975 have inoculated the system against a rerun.

And, as many have pointed out, to have the combination of three such characters as Whitlam, Fraser and Kerr, and similar circumstances, would be impossibly long odds.

The main characters are dead. Some of those still around from the time maintain their rage, lasting through the many years after that election campaign.

But what of the views of the young? Frank Bongiorno, professor of history at the Australian National University, says today’s students find the events “fascinating in the way political science and history students did in the late 1970s.

“But the high-stakes game that played out is a bit like ancient history for them. They would see it as if it was like contemplating Pericles of Athens or Caesar of Rome.”

Gough would be pleased enough with the comparison to Caesar Augustus. He did like to quote Neville Wran’s joking compliment: “It was said of Caesar Augustus that he found Rome brick and left it marble.

It will be said of Gough Whitlam that he found the outer suburbs of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane un-sewered, and left them fully flushed.”