Simon Birmingham: Australian visits by David Cameron and Wang Yi demand different diplomatic approaches

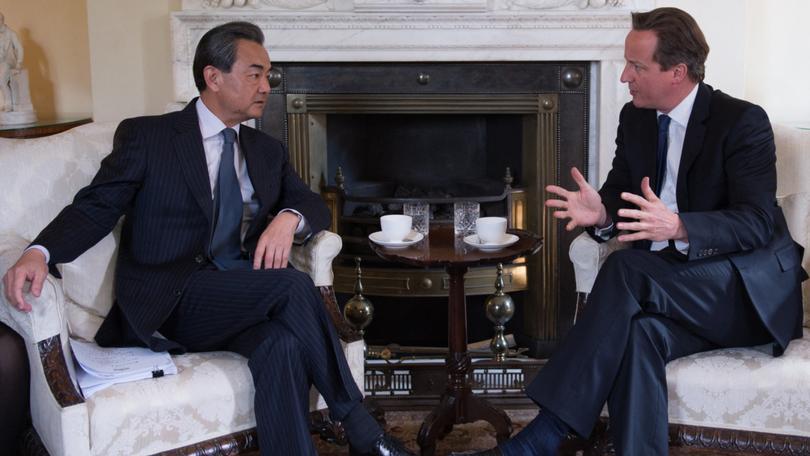

Their careers have followed similar trajectories, but Australia will approach meetings with China’s Wang Yi and the UK’s David Cameron very differently.

What do Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi and British foreign secretary David Cameron have in common? No, this isn’t a bad joke about an Irishman walking into a bar, tempting as that is straight after St Patrick’s Day.

This week, both Wang Yi and David Cameron are in Australia for unrelated but critical dialogue. Coincidentally, both are also deeply experienced politicians and leaders who have undertaken unexpected comebacks.

David Cameron, for six years the UK’s prime minister, surprised many by agreeing last November to end a seven year hiatus out of government and return to serve in Rishi Sunak’s government as foreign secretary.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.For more than nine years, including three that overlapped with Cameron’s time in the top job, Wang Yi served as China’s foreign minister. He stepped down at the end of 2022, only to return to the job seven months later after the mysterious departure from office of his successor.

On one level, these two visits mark a big week in Australian diplomacy. On another, they are part of the routine backwards and forwards established under agreements that create a regularity of dialogue between partner nations.

Despite these similarities, the visits entail relationships of stark differences.

In recent years our post-colonial history with the UK has found renewed vigour. New trade and defence partnerships sealed by the Morrison government are bringing our geographically distant countries even closer together.

The Australia UK Free Trade Agreement is reducing barriers for goods, services, investment and people to move between our nations. And AUKUS will see us work together, with the United States, to design and build the most sophisticated of submarine capabilities for our mutual defence.

With China, Australia has a longer standing free trade agreement than the UK. It was sealed by the Abbott government and helped lock China in as our largest trading partner, to the benefit of both our economies.

However, in recent years China has breached this agreement with the imposition of trade barriers against Australian producers. In so doing, the Chinese government damaged its own reputation globally as a stable trading partner, which further harms its own aspirations to join the regionally significant Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Winemakers, barley farmers, timber producers, coal miners, seafood exporters and beef processors are among those unfairly and unjustly penalised by the Chinese government, against the terms of the FTA we both voluntarily entered into, in an unsuccessful attempt by China to coerce Australia into changing our policies.

Military engagement between Australia and China has also become increasingly problematic recently, as a result of Chinese aggression.

Last November China’s navy deployed sonar pulses that caused injuries to Australian navy divers operating in waters near Japan. Chinese combat aircraft have released flares into the paths of Australian maritime surveillance aircraft in the South China Sea, while other Australian aircraft have been targeted by military grade lasers or subjected to “chaffing” incidents. We are not alone and have actually gotten off lightly compared with other countries in our region like the Philippines.

The nature of the Albanese Government’s dialogue with David Cameron and Wang Yi must, by necessity, be very different. The former will focus on shared objectives and advancing the work we are committed to pursuing together. The latter must strive to resolve or manage differences, while seeking out areas for common ground beyond the complementarity of our trading relationship.

We should build within these relations the blocks upon which peace and stability is secured for our region.

With the UK we do so through the strengthening of effective shared deterrence frameworks, creating stronger military capabilities that discourage others from conflict or the use of force.

With China we need to ensure misadventure, misjudgement or mistake do not escalate into conflict. We must argue for adherence to international laws and rules of conduct that reduce risks, while creating diplomatic channels for speedy resolution of any misunderstandings that do occur.

The stakes for Australia from how these two relationships are managed are high. They warrant bipartisanship where possible, but also clear demonstration of strength, clarity and a willingness to responsibly call out wrongdoing when it occurs.

Senator Simon Birmingham is the shadow minister for foreign affairs.