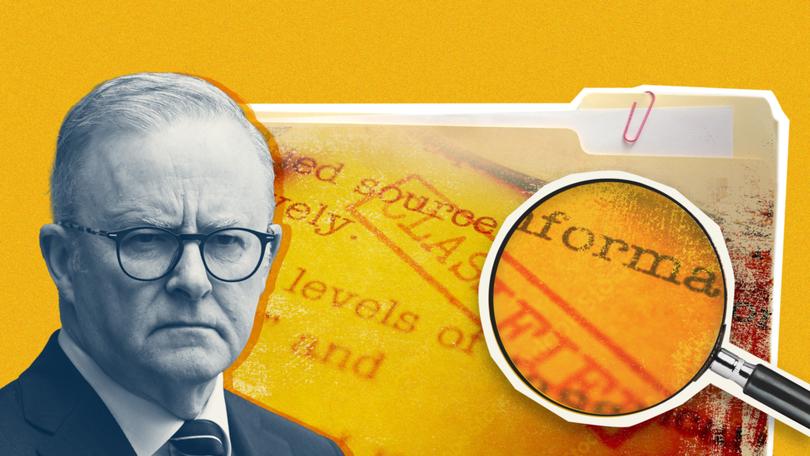

SIMON BIRMINGHAM: PM must explain Labor’s attempt to keep information hidden

SIMON BIRMINGHAM: A shocking leak has this week revealed the extent to which the Albanese Government is directing public servants to cover up information that should be made public.

In court proceedings the penalties for interfering with witnesses or evidence can be severe. So, should Parliament be any different?

A shocking leak has this week revealed the extent to which the Albanese Government is directing public servants to cover up information that should be made public.

These directions on how to obfuscate, evade and distort have come right from the top.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Labor’s guide to hiding information was written and distributed by the Prime Minister’s Office.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese promised to be a warrior for transparency, but instead has an office writing a manual to hide the truth.

In 2022 Mr Albanese said that “the Australian people deserve accountability and transparency, not secrecy.” Apparently the transparency standard only applied to other people, not Mr Albanese’s own Government.

What is it that Labor is trying to hide? Let’s start with the waste of taxpayers’ money.

In response to questions about retreats for public servants, the Prime Minister’s Office wants departments to say it “would be an unreasonable diversion of resources” to answer them.

The Albanese Government also seeks to hide evidence of whether its ministers seek appropriate briefings, or respond to briefs within timelines.

Instead, it only wants departments to say that officials “regularly meet” with ministers, and timelines apply “case by case.”

Labor’s answers are about as straight or direct as a roller coaster, and similarly just take you around in circles.

Remarkably, Labor is even directing public servants on how to withhold completely factual Budget information.

Ask individual government departments to detail where their budget has blown out and, if the advice of the Prime Minister’s Office is followed, you will be sent straight back to Go by being told to look at the Budget papers again.

In other words, get stuffed Mr and Mrs Public, we’re not going to offer even the most basic standards of accountability.

Many readers will no doubt be thinking that politicians don’t answer questions properly anyway. But this is different.

In this case we aren’t talking about Mr Albanese, Mr Dutton, me or any other MP weaving our way through a tricky interview.

These are written questions, seeking factual answers, that are expected to be prepared by public servants.

If this basic level of information is withheld from oppositions, minor parties, the media, and the public, then governments will face fewer tricky interviews because there will be fewer inconvenient facts in the public domain. Presumably that’s Mr Albanese’s objective.

Labor’s instructions to government departments on how to not answer questions strike a new low.

This represents a cover-up of anything that might be undesirable, with a blanket randomly thrown over great swathes of information that historically would have been made available to the Senate.

The Prime Minister’s self-approved ministerial code of conduct requires ministers to “observe standards of probity, governance and behaviour worthy of the Australian people.”

Through these directions to public servants Mr Albanese’s own office has clearly breached his own code. The question is: to what extent were the Prime Minister or any of his ministers complicit in this act?

If he pleads innocence or ignorance, will Mr Albanese denounce this document, and give proper instructions to departments to provide thorough answers to questions?

Should he run the Sergeant Shultz “I know nothing” defence, then Mr Albanese must be open about how these instructions came to be given by his office.

If the Australian media values basic standards of transparency and accountability, then it must ensure the Prime Minister either takes responsibility or takes action.

The Liberal and National parties will work with other non-government senators to get to the bottom of this blatant attempt to erode the powers and effectiveness of the Senate.

It is a long established principle of the Senate that hindering a witness or improperly influencing evidence constitutes a serious act of contempt.

It is impossible to read the Prime Minister’s directions to public servants as anything other than an improper attempt to influence the evidence given.

The Senate may not be a court of law. But it does have powers to compel and, where contempt is shown, to punish.

These powers are important and, in extremis, they can be used. However, Mr Albanese shouldn’t let it come to that. He should act, today.