Balibo Five and war correspondents’ current death toll highlights reporters risking it all to reveal the truth

CHRIS REASON: The business of war reporting has always been a dangerous one. But never as dangerous as it is now.

In a quiet corner of the landscaped surrounds of the Australian War Memorial, carved low into the ground, there is a permanent Memorial to War Correspondents.

The 2.4-metre wide, polished granite oculus sits in such low profile, you might miss it. But it sees you.

You see, it’s shaped like, and reminiscent of, a massive camera lens, bearing witness to all around it.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.And if you stand at the right angle, that stone lens gently reflects the distant shapes of the War memorial itself.

And that is the point: this is a tribute to those who gave their lives witnessing and recording history’s conflicts.

Yesterday marked the tenth anniversary of its dedication.

“We build memorials so that we shall never forget,” AWM director Matt Anderson told the crowd gathered at the Canberra memorial to mark the date.

He said the day was a chance to pause, commemorate and celebrate the often-forgotten sacrifices of journalists in war.

“To honour and re-dedicate ourselves to the men and women of the fourth estate who continue to fall into harm’s way,” he said.

“Because more often than not, it is only a journalist who can do it. And we are richer for the stories they tell.”

The memorial, conceived and fund-raised by the CEW Bean Foundation, carries these simple words on its stonework: “Amid the dangers known and unknown, war correspondents report what they see and hear. Those words and images live beyond the moment and become part of the history of Australia.”

The business of war reporting has always been a dangerous one. But never as dangerous as it is now.

Last year was officially declared the most lethal on record for war correspondents by the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

In total, 124 journalists were killed in global conflict zones in 2024.

Most of them, nearly two thirds, from Gaza alone.

In fact, the Gaza War, which is just weeks away from entering its third year, has not only claimed more journalists than World War I, but WWII, Korea, Vietnam, Bosnia, Afghanistan and Ukraine – combined.

A total of about 230 so far.

The figures have never been this high.

Yesterday’s service was attended by a staunch and sombre group of war veterans, Australian War Memorial custodians, Defence Force officials and journalists, current and retired, to remember the correspondents killed in war, especially the fallen Australians.

Bean Foundation Director Rodney Cavalier paid tribute “to the magnificent record of Australian correspondents.”

He also added a warning: “The cause of free speech in the West has not been under such sustained threat since the 1930s.”

Increased danger, urgent need

As the danger of war reporting escalates, perhaps the need for correspondents has never been more urgent.

Putting independent eyes on conflicts, recording the horrors as well as the heroes, taking the grim statistics and giving them names and faces, mothers and fathers, context and background, while trying to uncover some truths for what we like to call “history’s first draft”.

It’s what the Balibo Five were trying to do in 1975.

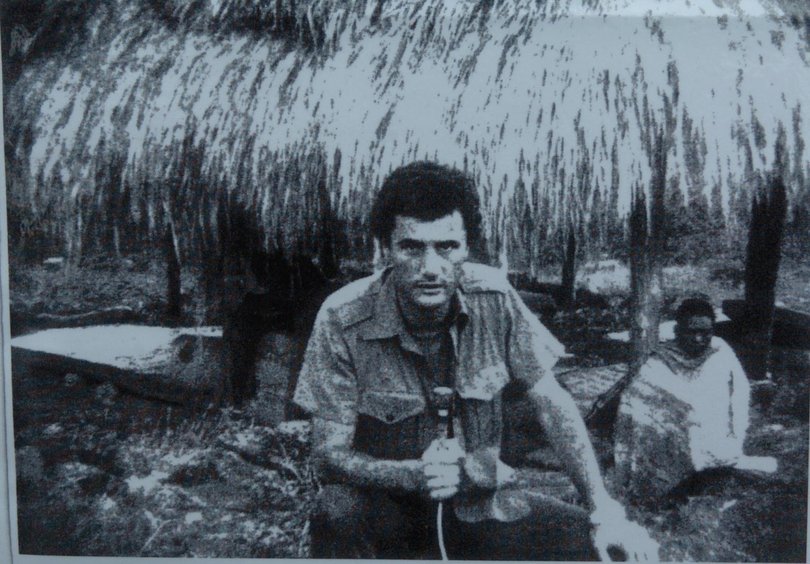

As the 50th anniversary of their brutal murders approaches on October 16th, there was special tribute yesterday to the five young Australian TV men who were gunned down trying to tell the world about Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor: Greg Shackleton, Gary Cunningham, Tony Stewart, Malcolm Rennie and Brian Peters.

Their motivation is forever recorded in the inscription on the wall of the Flag House in Balibo: “They did it in pursuit of the truth - and the cause of freedom”

I’ve thought about them a lot in my time on the road, it’s such a profoundly moving and important story.

I only began reporting on East Timor’s independence story in 1999, flying into the embattled, burning territory with the Australian troops on the first day of the INTERFET peacekeeping operation. There’s nothing like landing hot in the back of a Hercules and pouring off the back ramp into a conflict zone unsure if the enemy is ready to greet you with gunfire.

Which is exactly what happened to Sander Thoenes the very next day – the Financial Times journalist was shot and killed by a sniper while on the roads near Dili.

I travelled back and forth many times to cover East Timor’s painful independence story.

I’ve made the haunting pilgrimage out to Balibo and also travelled with Greg Shackleton’s heroic widow Shirley to the cemetery where the five of them are buried in Jakarta.

Shirley ran a tireless, lifelong campaign to have the remains repatriated.

Sadly, she died two years ago; and the remains are still in Jakarta.

Buried out of reach, like the thousands of documents held by the Australian Government that the families have been fighting to be released.

The Balibo Five story is one every young journalist should know. Especially if they’re a chance of being despatched to a war zone.

It’s such a powerful and tragic narrative.

The young men determined to expose what was happening on the ground, refusing to listen to the warnings to get out, believing that their profession and their Australian nationality would afford some protection.

It didn’t. In fact, it might have even added to their problems.

The five of them, hungry, enthusiastic, determined, driven – but completely unprepared for what was to happen next.

It pretty much describes any young reporter being dropped into their first war zone.

There’s nothing that can really prepare a reporter for war.

I remember with my first war zone – Bosnia 1993 – I managed to re-write the definition of “unprepared”.

My cameraman and I were in Rome Airport in transit from another story when the news desk rang to tell me the Serbs had just bombed a marketplace in Sarajevo – and killed 68 civilians. A massacre that looked like it might just tip the Americans into the war.

The desk said: “Go!”

The trouble was, we had none of the kit you need in a conflict zone - no first aid kits, maps, torches, sleeping bags.

And we certainly had no training. Neither of us had ever been to war.

And we had no food. And one thing I did know – you can’t turn up and leech off an impoverished community in a time of war. And while there’s a lot of Balenciaga and Gucci at Rome Airport, there was no duty-free Woollies.

The only food on sale we could find was a Swiss chocolate shop. So - we actually bought 10 kilos of fine Swiss chocolate.

As we were getting on board the British RAF Hercules plane to fly into Sarajevo - the cockney loadmaster looked at me as if I was mad.

He said: “What are you two going to do with this? Open a bloody sweet shop??!”

I was either desperate, deranged or diabetic.

The funny thing was, you can get a surprisingly long way in a war zone with 10kg of Swiss chocolate.

We used it to bribe our way through roadblocks; get lifts in military convoys; and generally spread cheer with locals. We managed to survive quite well.

Some, weren’t as fortunate in the early years of their war reporting careers.

I remember on that first assignment into East Timor in 1999 I met a bright young Australian cameraman called Harry Burton – he’d been in the business for only months. A former Coles quality control officer, he’d got bored, chucked it in, and got himself a handycam.

After a few months in East Timor he jumped to the Fiji coup, then to Afghanistan for Reuters. But by the end of that year, he’d been killed by Taliban in an ambush on the road from Jalalabad. Stoned to death then shot in the back.

His career as a combat cameraman had lasted less than 3 years.

There is a bit more support for war correspondents these days. We do battlefield first aid courses; travel with security escorts; install tracking apps on our phones.

In Ukraine, we used websites that tracked all the missile strikes and skirmishes – literally mapping the frontline live on the phone in your hand. Invaluable.

And in Israel, I joined a journalist’s WhatsApp group with a thousand members, which constantly updated on what was happening and where. Collegiate war corresponding; safety in numbers.

They were incremental improvements – but the bottom line is - war reporting is as perilous as it ever has been.

I’ve never considered myself a war correspondent by any stretch. I’ve parachuted into some of the world’s most significant conflicts over the last few decades, from Bosnia to East Timor, Afghanistan, Ukraine and Gaza, but I tend not to stay long.

Instead of the Year of Living Dangerously, I like to do three or four weeks of living dangerously and then get the hell out.

But I can tell you, there is nothing like war reporting: it is intoxicating and addictive.

With one hand you are reporting the complexities and human cost of war – and with the other, trying to juggle the logistics of staying alive.

Working out if you’ve got enough fuel to get to the frontline and back, enough food to last the week, or enough money to bribe the guards at the next roadblock.

You are constantly testing the motto of the legendary war photographer Robert Capa: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough”.

And simultaneously, you are updating your exit strategy in case it all goes pear-shaped.

You’ll make bonds with the locals, your fixers and translators that last a lifetime.

But you’ll feel guilt knowing that at any time you can get out, when the locals cannot.

You’ll witness horrors and be driven by the importance of documenting them on behalf of the dead.

You’ll see humanity at its very worst but also see it at its absolute best – and be inspired by the resilience, determination, strength and bravery not just of the soldiers but of citizens.

War reporting deals with all that and so much more. It’s high-risk, but it’s higher importance, next-level journalism.

And my grave fear is that the way the world is heading, we will be needing many more war correspondents in the years to come.