Productivity Commission finds Australian youth significantly disadvantaged by GFC, COVID and housing crisis

JACKSON HEWETT: It’s official. Australian youth have a rawer deal than their parents and pretty much every other generation of the post-war era.

It’s official. Australian youth have a rawer deal than their parents and pretty much every other generation of the post-war era.

That’s the view of the Productivity Commission, which has crunched the data and worked out that the cohort of youth who came into the workforce during the financial crisis and Covid started a few rungs down the ladder. Their inability to get into the wealth-creating housing market is making matters worse.

This ain’t no smashed avo emergency. This is a systemic issue that needs urgent repair.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It goes to the heart of our egalitarian beliefs and the core of our political system. It may also be a global phenomenon that foments global conflict to the detriment of us all.

Parents instinctively understand it.

Seventy per cent of Australian parents are pessimistic about their children’s financial futures, according to a global survey conducted in 2022. We are not alone in that concern, Europeans, Canadians and Japanese share a similar view.

Every generation born after the 1940s had a higher disposable income than the last, the Productivity Commission (PC) found for those born after 1990 that is not the case.

They got smashed first by the GFC, then COVID.

Unemployment, or underemployment stayed relatively flat, maxing out at 5 per cent for almost every cohort over the GFC/COVID decade. For 15 to 24-year-olds, it hit a high of 20 per cent.

“These young people that hit the labour force when the economy was weak struggled to get a job at their typical skill level. So you get people falling down these rungs and clustering of lower-skilled young people into part-time and casual work,” says Productivity Commission chair Danielle Wood.

Over that era, incomes for young people (those under 35) went backwards, while those over 35 went up, 65-year-olds and older most of all.

“Labor markets were weak, and it particularly affected younger Australians. Incomes for young Australians actually declined during that period, which is pretty extraordinary given the progress that we’ve seen (as a country).”

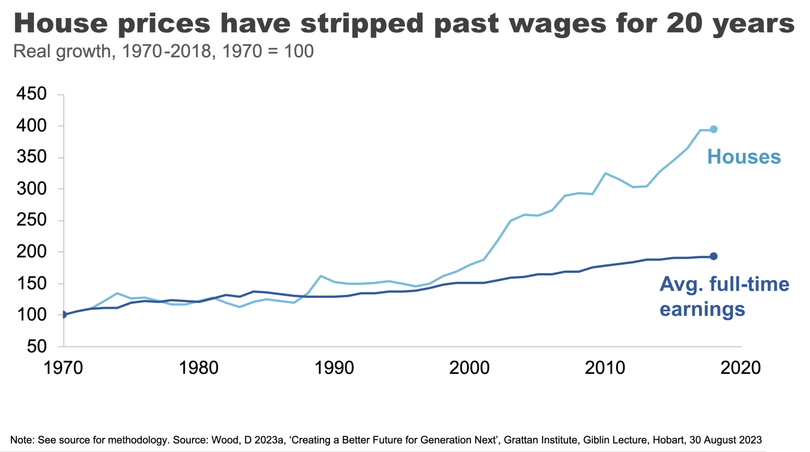

The income squeeze at one end was exacerbated by the house price explosion at the other.

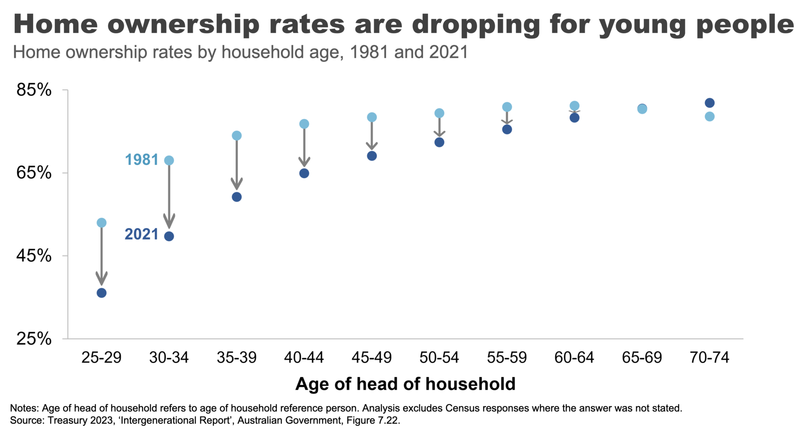

While those already on the property ladder watched their wealth soar, home ownership for young people has plunged.

Average full-time earnings have only grown 10 per cent since the GFC. House prices have doubled.

That means that compared to 40 years ago, 30-34-year-olds are 30 per cent less likely to own a home. It’s a trend seen across the board.

“We have seen, over time, a rising disparity in wealth outcomes amongst older and younger generations. Since about the 2000s, household wealth amongst older households has grown quite significantly, but amongst households under 35, it has lagged. If you owned a house before that period, you had a very large windfall gain in terms of wealth. If you are now a young person trying to get into the housing market, it is very difficult to do so,” Ms Wood said.

“We see that in declining rates of ownership by age, and this is even more pronounced if we just look for low and middle-income young people. High-income young people still tend to be able to get into the market, but for the rest of the income groups, it’s very, very difficult.”

That threatens the very fabric of our society.

Australia has one of the highest rates of economic mobility in the world, second only to Switzerland.

But without a serious push to solve the housing affordability issue, improve productivity and get wages growing again, those on the bottom rungs are in danger of being left behind and increasingly vulnerable to cost of living pressures.

Reserve Bank Governor Michele Bullock, speaking at the same ASIC event took up the baton for fixing the housing crisis and pointed out that the rate of housing supply is still dramatically behind where it should be for the RBA which is an inflation issue, with rents prices driving up CPI.

Rising inequality is spilling over into our electoral system, perhaps explaining why so many young people are turning away from major political parties and looking for extreme solutions on both the left and the right. The phenomenon is occurring worldwide.

Raphael Arndt, the chief executive of Australia’s $225 billion Future Fund sees it as a long-term risk, not just to the long-term savings pool but the global economy.

“The same drivers of wealth and income inequality, the feeling that my life’s not going to be better than my parents, those sort of drivers drive support for populist politicians,” Arndt said.

He sees a world where beggar-thy-neighbour trade wars and rising geopolitical conflicts will spill over into fractured supply chains, driving up inflation and interest rates and ultimately making life harder for all.

Ironically, those discontents voting for zero-sum game self-interest may be doing themselves a longer term disservice if it results in a world where interest rates push houses further out of reach and inflation makes costs of living concerns even worse.

“It’s really good to see here in this country, a good, open, robust debate about what we can do to alleviate those pressures,” Arndt said.