CIAN HUSSEY: Coalition split was a missed moment for political renewal

CIAN HUSSEY: A split in the Coalition could have sparked the kind of political realignment Australia hasn’t seen in decades. Instead, the chance vanished in days.

The short-lived split in the Liberal-National Coalition was a missed opportunity for a long-overdue political realignment.

Australians have recently been seeking a different kind of political representation. The decline in the primary vote going to the major parties and the rise of independent candidates is proof of this.

The Coalition clearly failed to appeal to voters at the recent Federal election.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

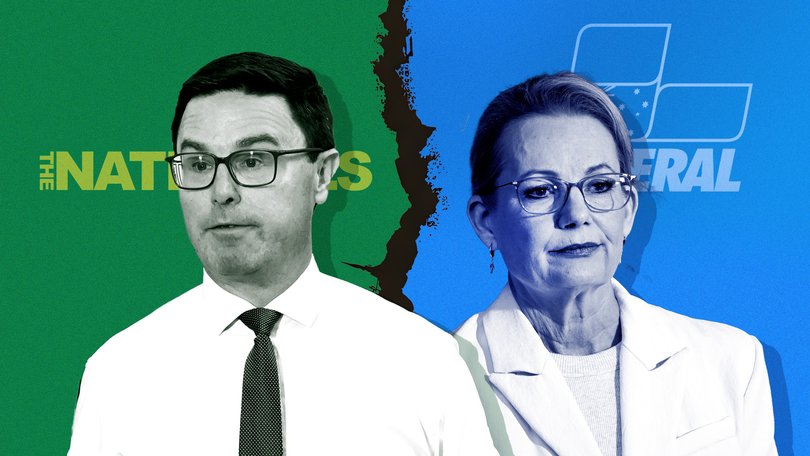

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.When David Littleproud forced a split, it appeared that there was about to be a period of self-reflection on the centre-right of Australian politics. An opportunity for the parties to ask themselves who they are, where they are going, and how they can be relevant to modern Australia.

But it now seems that the opportunity has been missed. In the hours after the break-up was announced, many expressed their anxious desire to see an immediate restoration of the coalition.

Some claimed that it would consign the Liberals and the Nationals to irrelevance.

Within a couple of days, the whole thing was called off.

This backtrack was shortsighted. Ironically, the founding of the modern centre-right came out of a very similar episode after the 1943 election.

Australia’s political history shows us that there is nothing frightening in new kinds of political representation. There is nothing odd about political parties coming and going, reforming and realigning over time to the changing desires of the Australian public. It just hasn’t happened in a little while.

But that doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t. In fact, it means it’s probably long overdue.

We should remember that the Liberal Party, the National Party, and the Labor Party have not always existed.

They may not always exist. This is not necessarily a bad thing.

The current Liberal Party is the second party of that name Australians have known. The first was created in 1909 as a result of the fusion of the Protectionist and Anti-Socialist parties, the latter of which had only three years previously changed its name from the Free Trade Party.

In 1901, the main division in Australian politics was between protectionists and free traders. By 1906, when it was apparent that Australians wanted protectionism rather than free trade, the leader of the Free Trade Party, George Reid, decided to realign the party’s priorities and name it the Anti-Socialist Party.

The main political debate, as he saw it, was no longer about free trade and protection, but Laborite socialism against anti-socialism.

The Labor Party was in government in 1916 when Prime Minister Billy Hughes caused a split over the question of conscription during World War I.

Hughes established a new National Labor Party, which formed a minority government with support from the Liberal Party until, in 1917, they joined to form a Nationalist Party.

The Nationalist Party ruled in its own right until the 1922 election, when the newly created Country Party (now known as the National Party) gained the balance of power in the Lower House. The Nationalist-Country coalition was formed.

In 1931, there was another split in the Labor Party when a group of dissidents, led by Joseph Lyons, broke away over differences about how the government should respond to the Great Depression.

Lyons and his followers merged with the Nationalist Party and formed the United Australia Party, which won the Federal election held at the end of the year.

In 1934, the UAP entered into a coalition with the Country Party, and they governed (with some disruption to their coalition agreement) until 1941, when two independents, who had been supporting the minority UAP-Country Party government, decided to bring it down.

The Labor Party formed a government instead, and John Curtin became Australia’s wartime prime minister.

Curtin’s Labor Party went on to win an emphatic victory at the 1943 election, much like the Labor Party under Anthony Albanese in 2025.

The UAP and Country Party terminated their coalition agreement, much like the coalition in 2025.

Unfortunately for Australians, that’s where the similarities end.

In 1943, a period of soul-searching resulted in the end of the UAP, which was largely folded into the new Liberal Party founded by Robert Menzies. It was a new party, with new energy and new policy ambitions for a post-war Australia.

Ahead of the 1946 election, the Liberal Party and the Country Party re-established a coalition, and although they lost that election, they had a significant win in 1949 and formed an astonishing 23-year government.

David Littleproud’s decision to force a split in the Liberal-National Coalition fits comfortably in Australia’s political history and traditions, even though some might be a bit uncomfortable with it because it does not fit well with our cautious culture.

It was not a radical decision anyway. It is hard to think of a less risky time to split a coalition than when it is in opposition and when it has just been rejected at an election, like what happened in 1943.

Far more daring splits and realignments have occurred, including during each of the two great global conflicts of the 20th century.

Australia has experienced a number of major political realignments and reformations.

Most of these have required the splitting of a party or coalition, or the creation of a new party or coalition.

Very few have occurred as a process of internal reform while keeping the branding the same.

The outcome each time this happened in our history was a better, more relevant representation.

Australians are clearly seeking something new from politics. A realignment could have met this desire.

To worry that a split may be happening, panic, and try to patch it up speaks to a level of short-sightedness and unwillingness to change that has afflicted the centre-right of Australian politics in recent years.

It speaks to a lack of the kind of leadership shown by a Reid or a Hughes or a Menzies to recognise when the time is right to change.

What could have been a generational opportunity for reform and renewal appears to have been wasted. Australians will be left worse off for it.