THE ECONOMIST: How Trump, Starmer and Macron can avoid a debt crunch

With deficits soaring, their finance ministers will have to be smart

America’s gross national debt is $36 trillion, or $107,000 per person. It is rising fast and will probably soon be rising even faster. If Donald Trump’s election campaign was anything to go by, his return to the White House heralds a flurry of tax cuts on everything from corporate profits to tips.

In the fiscal year that ended in September, Uncle Sam spent $1.8 trillion more than he collected in taxes (6.4 per cent of GDP, or over double the annual earnings of America’s seven biggest firms). By one estimate, Mr Trump’s agenda could raise borrowing by $4.1 trillion in the coming decade.

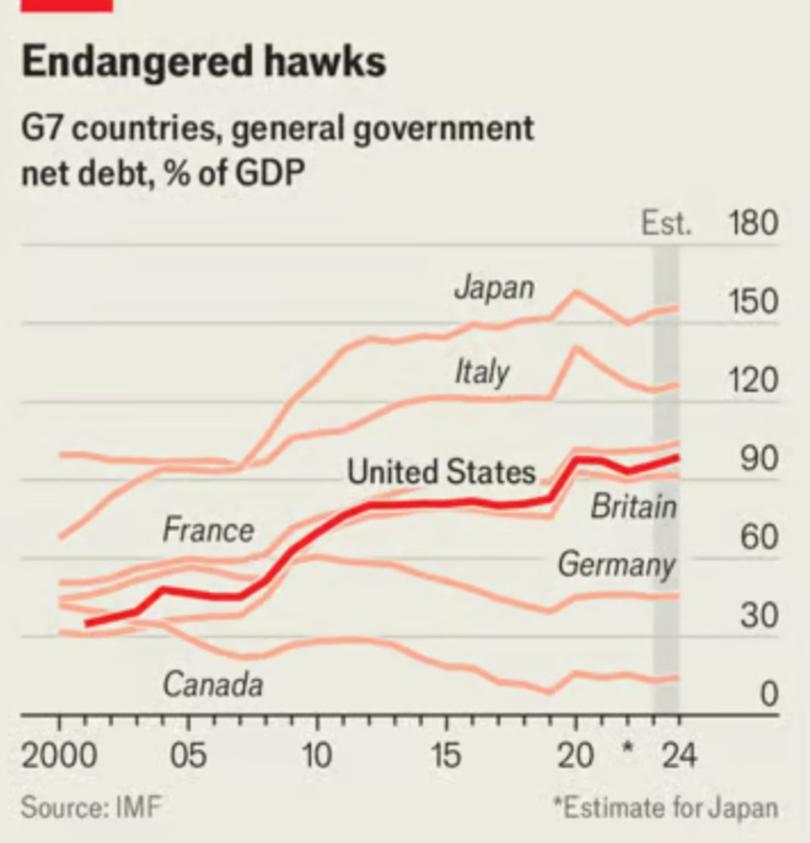

It is not just America — politicians across the Atlantic are only a bit less profligate.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The euro area’s deficit is 3.6 per cent of economic output, and those of several big members — France (5.5 per cent), Italy (7.2 per cent), Poland (5.3 per cent) — are higher. China’s public debts, smuggled by local governments into opaque financing vehicles, exceed 120 per cent of its GDP and will rise to nearly 150 per cent by 2027. India’s deficit is approaching 8 per cent of its GDP; Brazil’s a hair-raising 10 per cent.

Although no finance minister thinks this situation can go on for ever, you would search in vain for serious political will to correct it.

Scott Bessent, Mr Trump’s pick for treasury secretary, has in the past been concerned about the size of the deficit. But he will have to contend with a president who shows little interest in being prudent.

Rachel Reeves, Britain’s chancellor, talked tough on fiscal policy while in opposition. Then one of her first acts in office was to raise borrowing by £30 billioin a year ($38 billion, or 1.2 per cent of GDP). Voters, at least in their leaders’ imaginations, simply will not tolerate higher taxes or spending cuts.

A crucial task for many of today’s finance ministers, unable to run a balanced budget, is therefore to buttress a lopsided one.

Ms Reeves should be keenly aware of the dangers. Two years ago, her predecessor-but-one proved that debt crises are not just for emerging markets by announcing a bevy of unfunded tax cuts without care for the fiscal consequences. Gilt yields rocketed, causing prices to crater, big pension funds to court bankruptcy and the prime minister to be ejected from office.

Here, then, is a spendthrift politician’s guide to placating the bond-market vigilantes.

The task boils down to three questions. First, and most fundamentally, who should you borrow from? This sets the constraints for questions two and three. These are what form the debt should take (think currency, maturity and instrument), and how to keep borrowing costs from rising so high that they snowball exponentially.

Take the decision on who to borrow from first. The obvious choice is between domestic investors and foreigners; a second is between individuals and financial institutions.

At first glance, domestic investors of both types might seem an easier crowd. In rich countries, government bonds are as close as they can get to a “risk free” asset, making them less likely than foreign ones to stage a “buyers’ strike”.

Inducements, meanwhile, are easier for a government to offer to citizens. National pride might work — think of the 20th-century posters exhorting patriots to buy war bonds. Tax breaks can help, too, such as Britain’s exemption of gilts from capital-gains tax. Banks can be nudged to hold bonds with less onerous regulation. An example is the EU’s margin requirements for derivative positions, which are lower if government bonds are used as collateral.

But there are downsides to sinking domestic capital into sovereign debt. It is not only that there is less left to invest in the private sector. Layna Mosley of Princeton University notes that domestic investors, having better access to information, are often the first to dump a country’s bonds if its fiscal situation deteriorates. What is more, if households and local banks are heavily exposed to government debt, any restructuring or default might be politically impossible. Governments will then also struggle to restructure debt to foreigners, who will not accept losses from which domestic bondholders are exempted.

The second decision, on what form debt should take, is as thorny. Issuing bonds on the public markets helps drum up demand, but puts the country’s weak finances under the spotlight. It also invites continuous judgment from traders. Untradeable debt, including loans from commercial banks or other countries, dodges publicity but costs more. The wrangling required by loans from multilateral outfits, like the IMF, ensures they are a last resort.

What is the ideal length of borrowing? Long-term debt is usually more costly, but puts off the need to refinance. This limits damage if bondholders sour on the country, or if rates start rising.

Take America’s sovereign debt, with an average maturity of six years, meaning much of it was issued when money was cheaper. As a result, Uncle Sam paid an average interest rate of 3.4 per cent in the fiscal year that ended in September — lower than the 4.4 per cent now available on ten-year Treasury bonds.

Most important is the choice of currency.

Rich countries can issue debt in their own, which investors trust their central banks not to devalue. Countries with poorer records may struggle to market local-currency debt abroad. Even those that can do so may choose to issue at least some debt in American dollars, in return for lower interest rates.

The snag was demonstrated vividly by the Latin American and Asian debt crises of the 1980s and 1990s. Foreign-currency debts are vulnerable to a doom loop in which a plunging exchange rate makes them unaffordable, which causes the currency to devalue even more.

Moreover, countries borrowing in their own currency have far more scope to suppress interest rates that threaten to make their debt unsustainable — the third challenge of running a large deficit.

“Financial repression” might horrify free-market types, but there are endless ways for governments to enact it. Most, says Carmen Reinhart of Harvard University, boil down to creating a captive audience for the debt. Chinese-style capital controls prevent the population from stashing savings abroad; caps on bank deposit rates can nudge them to higher-yielding sovereign bonds.

More effective still is forcing banks to buy the debt. Jason Tuvey of Capital Economics, a consultancy, points to Turkey, with 40 per cent of its debt in lira, as a prime example. Starting in 2022, a barrage of new rules obliged local lenders to buy government bonds. Combined with pressure on central bankers to loosen monetary policy, this sent the yield on ten-year debt plummeting, from 24 per cent in September 2022 to 9 per cent in May 2023. Once both policies were reversed, the yield shot back up above 25 per cent.

The need for a reversal shows how painful financial repression’s side-effects can be. Suppressing the central bank rate risks rampant inflation (which in Turkey rose to 86 per cent); forcing lenders to fund the deficit makes matters worse. Penalising them for lending to the private sector, not the government, may result in loans drying up — a high price to pay for cheaper debt.

Although it might seem that rich countries would balk at such measures, a paper in 2015 by Ms Reinhart found that similar policies were exactly how many shrank their debt after the second world war.

Asked if they could be repeated, Ms Reinhart points to post-financial-crisis rules in places such as America, Britain and the EU forcing banks and pension funds to “recapitalise” and hold more liquid assets — meaning government bonds. The intended target of these rules, she says, might be financial stability. But “if it quacks like a duck, if it has feathers, if it swims, it’s probably a duck.”

The catch is that fears of inflation, which electorates loathe, have now returned with a vengeance. Governments might think fiscal restraint will cost them re-election; America’s Democrats went nowhere near austerity and were still booted out of office by voters sick of rising prices.

Any hint that their borrowing made inflation worse would probably see politicians elsewhere treated similarly. That leaves either belt-tightening or the risk of imitating Britain’s gilt market crisis of 2022, which would seem certain to trigger defenestration.

In the end, any strategy for running large deficits bangs up against an iron law: you have to stop at some point.

Originally published on The Economist