THE WASHINGTON POST: The Haitians of Springfield, a Trump campaign target, brace for his presidency

Throughout the election, Donald Trump spread lies about Haitian immigrants. He pledged they’d be the first group deported if he won the White House. Now he has, where do they stand?

SPRINGFIELD, Ohio — This was the worst-case scenario for Yvena Jean François, but she willed herself to thank God.

That’s what the Haitian immigrant did on her toughest days. That’s what she did when one of her friends was shot and killed back home in Port-au-Prince. As a Christian, she said, she had to trust the Lord’s plan.

“Even when it hurts,” she said early Wednesday, right after opening her eyes to see that Donald Trump had easily won back the presidency.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.And it stung. Trump had berated immigrants living in this predominantly White corner of southwest Ohio throughout his campaign. During the presidential debate, he’d regurgitated a debunked rumor that they were eating dogs and cats. Then he’d pledged to launch “the largest deportation in the history of our country,” starting with the Haitians of Springfield.

Most are in the United States legally, city officials have reiterated. But they are not citizens, so they could not vote. Instead, the roughly 12,000 Haitians who live here headed to work or stayed home, many glued to election coverage, as their American neighbours cast ballots that could shape their fate.

They knew that some residents see them as a threat, despite city officials recruiting immigrants to help resuscitate a sagging economy. Some believed they’d taken jobs, crowded hospitals and drove dangerously. Others, though, had been unfailingly kind, stopping by Haitian support offices to donate clothing and electronics.

Election results showed that Trump won Springfield, but by a narrow margin of less than 150 votes of the roughly 20,000 cast.

François, 39, had settled in Springfield three years ago. The driveway to the polling place near her duplex had been lined with Harris-Walz signs.

She’d worked as a television journalist in Haiti, documenting the country’s harrowing gang takeover - the kidnapping, rape and murder. Seeking safer ground, she fled to the United States and eventually found work at an Amazon warehouse. The $19-an-hour checks covered her rent and gradually funded her own podcast studio, from which she proudly broadcast U.S. news to listeners in her Caribbean nation.

Now she didn’t know what to tell them.

“I don’t know,” she said, “if I can continue to pursue my dreams.”

Throughout American history, plenty of leaders have bashed immigrants. But never before has a presidential candidate — let alone a victorious one — vowed to banish a specific group from a specific city.

Decades ago, Springfield’s reputation glowed. Newsweek heralded it as the epitome of the “American dream” in a 1983 edition that depicted families washing fancy cars and enjoying the county fair. But the population dwindled as factories shuttered. Victorian mansions downtown crumbled. Young couples packed up.

City commissioners launched an effort to court immigrants in 2014, and by this year, the mayor estimates Springfield’s population had climbed by about 25 percent, mainly because of Haitian newcomers.

By all accounts, though, the government has struggled to keep up with the growth. Irritation exploded into outrage in August 2023 when a Haitian driver without a valid license struck a school bus, injuring 23 children and killing an 11-year-old boy. Despite pleas from the boy’s parents not to politicize his death, Trump joined conservative politicians and pundits in lambasting Haitians as proof of the Biden administration’s immigration failings.

Viles Dorsainvil had been optimistic that the fury would dissipate. So optimistic that his organization — the Haitian Community Help & Support Center — had recently made an offer on a larger building for their growing community, the now-defunct Fire Station 8.

Sure, some council members had pushed back, asking why the red-brick property couldn’t be converted into a homeless shelter. But Springfield ultimately authorized the sale. Soon, they’d host English classes and driving lessons there.

Yet the hostility raged on. He’d lost count of how many Haitians have reported harassment to his group — like drivers unrolling their windows to yell, “Go home!” Over the weekend, one shaken young woman told him that she’d been walking down Selma Road to an employment agency when a truck skidded to a stop. A door flung open. The man inside yelled, “Get in!”

“Maybe an attempted kidnapping,” Dorsainvil, 38, reckoned. He thought of his cousin back in Port-au-Prince. After she’d been abducted, he’d paid $500 for her release.

As signs began pointing to a Trump comeback, Dorsainvil and his team consulted with immigration lawyers. Nobody could be deported overnight, they reasoned. Plus, Trump had sought and failed to revoke protections for Haitians back in 2018. (Temporary protected status benefits for Haitians aren’t due to expire for another 14 months and three weeks.)

“This is still the land of law and order,” Dorsainvil said.

Still, fearing unrest, his organisation is locking down through Thursday.

Americans here are split. Some insist they aren’t prejudiced — that the government is to blame for failing to accommodate a population surge. The language barrier has vexed many, they said, and the “Make America Great Again” vitriol made some feel seen.

“As people started to move in, the city wasn’t prepared,” said Julie Spencer, 63, who was born and raised here, “and there lies the problem.”

The retired trauma nurse voted for Trump, but she didn’t believe that her candidate would actually deport the Haitians. He’d be more likely to launch a stronger vetting process, she thought, dismissing his vow to remove the city’s foreigners as campaign talk.

Hours before the polls closed, two first-time voters emerged from Covenant United Methodist Church with “Ohio Voted” stickers on their T-shirts and conflicting hopes for their Haitian neighbours.

Selena Greene, 20, had laboured at an Amazon warehouse with several of the immigrants. She loved that some could speak French, the other dominant language in Haiti.

“That was so cool to me — I had no idea,” said Greene, who has lived here on and off since eighth grade. “My dream vacation is Paris.”

Haitians were her friends and across-the-street neighbours. She’d enjoyed learning about their culture. More impressive was their commitment to the job — “The hardest workers,” Greene said. She’d opted to support Vice President Kamala Harris, hoping they could stay.

Gage Jenkins, 18, voted for what he saw as a better path.

Trump, he trusted, would reduce the strain on Springfield’s resources by guiding some of the immigrants elsewhere.

“Not deport them back to Haiti,” the technology student at a career-training school clarified, “but help more evenly spread them across the country.”

He’d just travelled an hour to take the exam for his driver’s license, he said. The wait to book that test in Springfield had stretched five weeks long. Back in 2018, his sister had been able to schedule one with a couple days’ notice.

“We’re overwhelmed here,” Jenkins said.

Across town Tuesday night at a Haitian eatery, the television on a pink wall was switched off. No election broadcasts here. Digging into a bowl of vegetable stew, Mia Perez said she needed a break, anyway.

The 33-year-old immigration attorney had been scrolling TikTok in bed — “with a blanket over my head,” she joked, poking at her anxiety.

Her father was Cuban, and like that side of her family, she normally supported Republicans. Her mother was Haitian, so this time Perez had worn a blue dress to vote for Harris.

She hated the way Trump spoke about her community — “attacking people based on made-up rumors,” she said. Perez planned to put up a fight if he pushed forward with his plan to deport them.

“I’ll be ready to represent them,” she said.

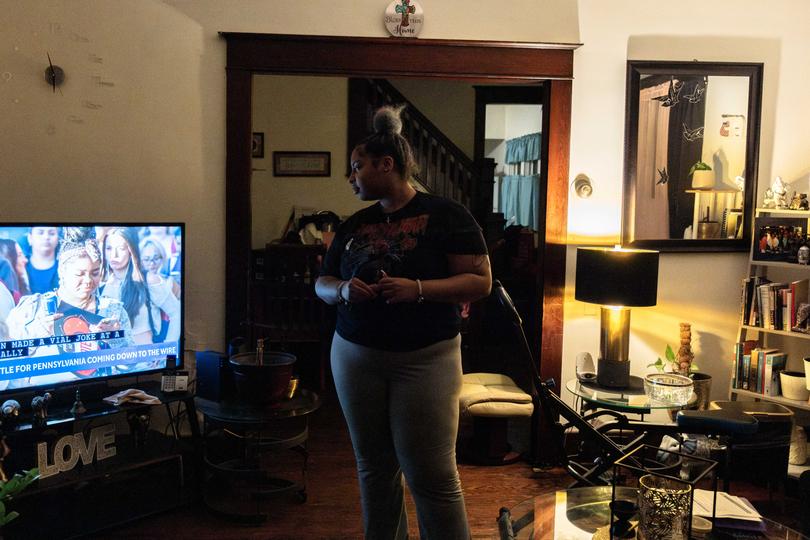

The screens stayed on at François’s duplex. NBC anchors chattered on the 85-inch television in her podcast studio. “It’s an incredibly tight race,” reported one - hours before it suddenly wasn’t.

As her future hung in the balance, François stayed home. She’d seen the Trump signs around town. Freedom of speech, she’d thought, brushing them off. But she couldn’t understand how anyone could approve of a leader who said he “wouldn’t mind” if someone fired at the news media at his rallies.

That remark scared her. The friend who’d been killed in Haiti was a journalist. She dreaded worrying about that kind of violence in America. It was stressful enough not knowing if she could stay.

- - -

Adriana Navarro contributed to this report.

© 2024 , The Washington Post