THE ECONOMIST: Dictator or not, Trump should be able to govern unhindered with his sycophantic inner circle

Donald Trump’s second victory was resounding. And with Congress unlikely to be much of a hindrance, his second term will be too.

When Donald Trump claimed victory in the wee hours of November 6 before a fawning crowd at Palm Beach County Convention Centre, he did not have a single vituperative word to say.

He aired no grievances and made no direct criticisms of his defeated rival, Kamala Harris, or her boss, the incumbent president, Joe Biden.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Gone was the angry, crude and vengeful candidate of the final weeks of the campaign. Instead, Mr Trump pledged to unite a divided nation — just as he did with surprising graciousness in 2016 before initiating four years of chaos.

This time Mr Trump’s victory was even more resounding, if less surprising.

For the first time in his three recent campaigns for president, he won the popular vote. He appears poised to win all seven swing states, giving him an even bigger margin in the electoral college than in 2016.

All 50 states shifted rightward. And all this despite being impeached twice, defeated in the election of 2020, prosecuted four times, convicted of multiple felonies and found liable for sexual abuse, not to mention being shot on the campaign trail. It is arguably the most remarkable political comeback in American history.

“If you want to make somebody iconic, try to throw them in jail, try to bankrupt them ... All those things failed. They just made him bigger and more powerful as a political force,” exulted Roger Stone, a Republican operative.

Foiler’s failure

It was just this outcome that Mr Biden had promised to ward off when he announced he would run for a second term in April last year. His and his aides’ decision to hide his decline from the American public and press ahead now looks unspeakably selfish. When his party at last forced him to stand down in July after a disastrous debate performance, there was little time or appetite for a competitive primary.

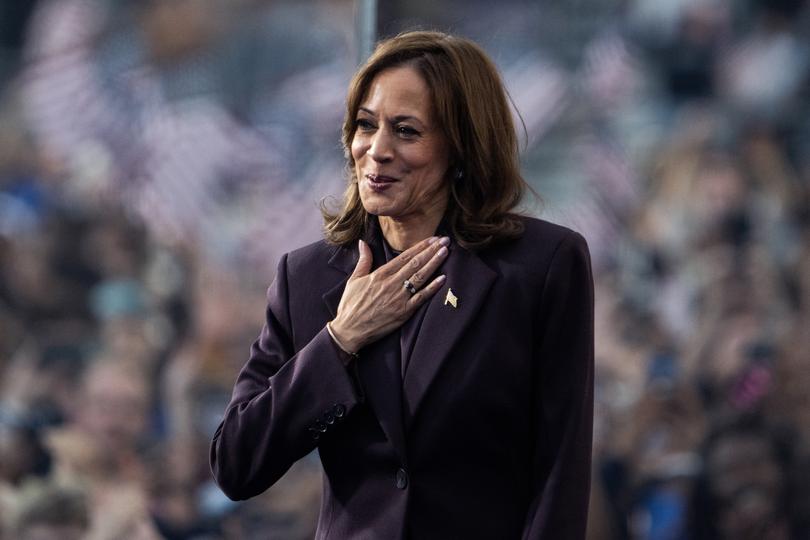

That allowed him to anoint Ms Harris, handing the Democratic nomination to a woman whose previous campaign for president, in 2020, had quickly collapsed.

Ms Harris’s strategy was to renounce past progressive positions for new moderate ones and to eschew difficult interviews in order to avoid explaining herself. When asked where she differed from the unpopular Mr Biden, she said, “There is not a thing that comes to mind.”

This Ming-vase strategy might have worked if she had been the overwhelming favourite, but for an electorate upset over inflation and illegal immigration, she does not appear to have represented meaningful change.

Ms Harris underperformed Mr Biden across the board. Rather than flipping Texas, a long-standing Democratic pipe dream, Ms Harris lost it by 14 points.

In several states where she was expected to romp home, she won by fewer than 10 points, including Illinois, New Jersey and Virginia. Her 11-point win in New York was the Democrats’ worst performance in the state since 1988.

Ms Harris seems to have haemorrhaged support among Hispanic men, in particular, a grave injury to the Democratic coalition. In 2016 Democrats won 64 per cent of the vote in Miami-Dade County in Florida; in 2020 that fell to 53 per cent; this year they mustered only 44 per cent.

Although Ms Harris did better in whiter areas, particularly those with lots of college-educated voters, she also lost ground in cities, which are typically powerhouses of Democratic support.

Mr Trump gained the most ground in places with high inequality, rising housing costs and large foreign-born populations.

For every percentage point of foreign-born residents above the national average in a given county, the Democrats’ share of the two main parties’ votes decreased by 0.17 percentage points between 2020 and 2024.

In the days leading up to the election, when it became clear that Ms Harris’s poll numbers were uncomfortably close, Democratic operatives self-soothed by insisting that female voters would push her to victory, perhaps in defiance of their husbands, out of their fury at the Supreme Court’s voiding of the constitutional right to an abortion in 2022.

Discontent at that decision was indeed manifest: voters in Arizona, Missouri, Montana and Nevada comfortably approved referendums enshrining the right to an abortion. But that did not stop many of them from voting against Democratic candidates at the same time. In Florida, a referendum to protect the right to abortion up to the point of fetal viability nearly met the required threshold of 60 per cent, even though the State as a whole voted for Mr Trump by 13 points.

Some Democrats are consoling themselves by arguing that incumbent parties all over the world have been rebuked by economically disgruntled voters, including the Tories in Britain, Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance in France and the LDP in Japan.

The difference, however, is that the economy has grown rapidly in America and real wages are increasing. The Federal Reserve has largely quelled inflation and started cutting interest rates. Although Ms Harris largely failed to differentiate herself from her boss, she did at least sound empathetic about rising costs and offered (misguided) remedies such as banning price gouging. Yet discontent remained high.

Democrats who are tempted to explain away Ms Harris’s defeat as part of a global wave of anti-incumbency may be missing something more fundamental.

In 2016, when Mr Trump defeated Hillary Clinton, Democrats dismissed the result as an electoral college aberration fuelled in part by racism, sexism and Russian disinformation. But this year, with Mr Trump winning the popular vote with the backing of a multiracial, working-class coalition, such arguments are harder to sustain. It is also difficult to prove that Ms Harris suffered from sexism given how little she emphasised her gender during the election, says John Sides of Vanderbilt University.

“People scratch their heads, like, ‘Oh, these Latino men, these black men, why are they moving to Trump?’ And the answer is, they’re conservative,” says Lynn Vavreck of the University of California, Los Angeles.

The Democratic turn in recent years towards left-wing identity politics, with talk of decriminalising illegal immigration, defunding the police and championing critical race theory, did not endear them to minorities, as intended. Even though Democrats like Ms Harris had recanted such views and begun to ape Mr Trump’s approach to crime, trade and immigration, they failed to stanch their losses among black and Hispanic men and unionised workers.

Democrats also believed, wrongly, that wavering voters would spurn Mr Trump because of his conduct on January 6, 2021, when a mob of his supporters stormed the Capitol in order to overturn his defeat in the 2020 presidential election.

What politicians call negative partisanship, or the contempt for the other side, is especially potent in America’s two-party system.

“The doom loop is real and getting worse. It was an extremely nasty and ugly election … yet people voted for Trump largely because he was the Republican,” says Lee Drutman of the New America Foundation, a left-leaning think-tank.

The only candidate voters did in effect disqualify for the presidency was Mr Biden— because of his age, not his conduct. A triumphant Mr Trump (who is himself 78 and at times wobbly on his feet) now returns to the Oval Office in less than 75 days.

Avenger’s advent

When conceding the election on November 6, Ms Harris enjoined Democrats to nurture “optimism” and “faith” even if they feel America is “entering a dark time”.

Mr Trump will take the oath of office on the western steps of the Capitol on January 20, 2025, returning to power democratically at the site where four years ago his supporters attempted to install him by force. He has pledged “within two seconds” to sack Jack Smith, the special counsel who has charged him with crimes over his handling of classified documents and his attempt to subvert the election of 2020. (Mr Smith, acknowledging the inevitable, is reported to be calling off the prosecutions already.)

Mr Trump once mused that he might behave like a dictator on his first day. “We’re closing the border, and we’re drilling, drilling, drilling. After that, I’m not a dictator,” he said.

Dictator or not, Mr Trump should be able to govern relatively untrammelled. Democrats have forfeited control of the Senate, losing seats in Ohio, Montana, and West Virginia. Republicans will hold at least 52 seats in the 100-seat chamber. This should allow Mr Trump’s judicial nominees to win confirmation, including those to fill any vacancies on the Supreme Court. It will also give Mr Trump a relatively free hand to pick whomever he wants in his cabinet and other senior jobs.

Although moderate Republican senators such as Susan Collins of Maine or Lisa Murkowski of Alaska may object to wildly unqualified judicial or executive-branch nominees, they will have to pick their battles. The leadership of the Republicans in the Senate is expected to be equally circumspect. Worse for Democrats, their chances of reclaiming the chamber in 2026 also appear slim, since there will be few seats up for election that year that Democrats might plausibly flip. Mr Trump may thus end up appointing a majority of the nine members of the Supreme Court, having already picked three justices in his previous term.

In order to pass much legislation, Mr Trump will need Republicans to control the House of Representatives, too. That may yet happen. Control of the chamber will be in doubt for several more days as very tight elections in slow-to-count states like California are settled. It would be quite unusual, however, for a new president to win office without his party winning the House.

Betting markets, at any rate, are supremely confident that Republicans will end up in control of Congress as well as the presidency.

During his first term, Mr Trump squandered much of his legislative capital on a failed attempt to repeal Obamacare. His signature piece of legislation, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), was largely delegated to the Republican leaders of the day, Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell, neither of them MAGA types.

This time Mr Trump is likely to be dealing with more accommodating leadership. Congress will want to craft an extension to the personal tax cuts of the TCJA, many of which expire next year. Judging by recent practice, that bill is likely to become an omnibus for Mr Trump’s fiscal priorities, which could include a clawback of some of Mr Biden’s green subsidies and congressional authorisation for some ferocious tariffs in order to pay for the many further tax cuts that Mr Trump promised while campaigning.

Of course, Mr Trump was previously uninterested in the grinding legislative process and more attracted to the exalted powers of the imperial presidency.

He would wield his authority with immediate effect. Having pledged mass deportations of the 12 million or so illegal immigrants in the country, Mr Trump would make a show of following through, despite the massive logistical and legal obstacles.

Similarly, Mr Trump will feel compelled to begin raising tariffs on most imported goods, and especially on imports from China. This would prompt immediate legal challenges in America and perhaps retaliatory tariffs abroad. He will use his power to pardon to exonerate not just himself of the various federal crimes with which he has been charged, but also those convicted for violent offences on January 6.

The defanging of the deep state that Mr Trump promised in the first term would also get underway much more determinedly this time. The intelligence community is bracing for impact, as are senior civil servants in policymaking roles.

Mr Trump would like to make it much easier to sack them. Anxiety among foreign diplomats will also increase. American allies in Europe are nervously contemplating what might happen if Mr Trump were to cut support for Ukraine abruptly or seriously undermine the NATO security alliance. China will eye him warily. The allies in Asia that Mr Biden spent years wooing will wonder whether their courtship with America is over.

A lot will depend on whom Mr Trump appoints to big jobs.

There is ample reason to worry. Most accomplished Republicans refused to serve in his first administration and many of those who thought they could stomach it ended up bowing out. The riot on January 6 led to a further dwindling of the ranks.

There are still a few adults vying to be in the room, including Scott Bessent, a billionaire investor who aspires to be treasury secretary, and senators such as Bill Hagerty of Tennessee or Tom Cotton of Arkansas, who are said to be contenders for secretary of state and defence respectively. But Mr Trump’s inner circle is composed chiefly of sycophants and chancers. A kakistocracy is a society governed by the worst and least qualified. It may be a useful word over the next four years.

Unprincipled protectors

Mr Trump’s secretary of homeland security, whoever that may be, will face the difficult task of carrying out a mass hunt for illegal immigrants, probably in the face of widespread public resistance. Even more important will be Mr Trump’s choice for attorney-general.

Although Democrats assailed Jeff Sessions and Bill Barr, attorneys-general in his first term, for ignoring the law to pander to Mr Trump’s preferences, both turned out to have more spine than Mr Trump, at least, considered appropriate. He is likely to pick a more supine candidate this time around.

The president-elect has sweeping plans for the justice department: he wants it to abolish its independence and turn it into a personal legal army to undertake selective prosecutions of his political enemies. He sees this as revenge for the prosecutions he has had to endure.

Although Federal judges are likely to put a stop to the worst of Mr Trump’s impulses, their interventions will also become less frequent as the president’s appointments gradually change the composition of the judiciary.

Mr Trump has plainly established himself as a transformational figure in American politics. He has completely reshaped American conservatism, forcibly converting it to nativism, mercantilism, welfare-statism and isolationism.

The old Republican elite, whose members either pointedly refused to support him or even endorsed Ms Harris, has been thrown out on its face. Unlike Mike Pence, JD Vance, the vice-president-elect, is an eager acolyte of Trumpism who is heir apparent to the movement when Mr Trump’s time in power ends in 2029.

The Trumpist revolution has not just captured control of the Republican Party and the White House (again), it is also spurring a reformation in the way that parties of the right all over the world conceive of conservatism.

Trumpist populism is on the march. The Democrats, as Ms Harris’s defeat vividly illustrates, have yet to come up with a formula to halt its progress.

Worse, many of them also seem to be in denial about the extent of the problem. America’s constitution may limit Mr Trump to one more term in office, but it does not provide any restrictions on the spread of his ideas.