THE WASHINGTON POST: Trump has a plan to remake the economy. But he’s not explaining it very well.

THE WASHINGTON POST: Trump acknowledges his economic plan is causing short-term pain while the nation advances to a ‘Golden Age.’ But administration officials have been much less clear about the destination.

President Donald Trump acknowledges that his economic plan is causing short-term pain while the nation advances to a new “Golden Age.” But administration officials have been much less clear about what that destination will look like —and how long it will take to get there.

The president talks about reindustrialising the Midwest while his treasury secretary emphasises weaning Americans from an unhealthy reliance on government spending. Trump’s commerce secretary is keen to balance the federal budget. His top White House economic adviser touts the virtues of tax cuts and “massive deregulation.”

Amid signs of investor unease, the Trump administration insists it aims to help Main Street, not Wall Street. But so far, the administration’s discordant chorus is not satisfying either one. The erratic pace and tone of Trump 2.0 is taking a toll on the stable economy the president inherited, denting growth prospects and leaving Americans more downbeat than they have been in years.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.On Friday, a closely watched consumer confidence index sank to its lowest level since November 2022, when inflation was near a 40-year high. The stock market, meanwhile, is losing altitude, as investors fear that the president means what he says about using tariffs to reverse decades of globalization.

“It is a bit of a muddle right now, what they mean. Each of the economic spokespeople speaks in different ways. And I’m not even saying they’re speaking in different ways about the same thing. They’re just speaking about different things,” said economist Glenn Hubbard, who was President George W. Bush’s top economic adviser. “It’s unsettling.”

Trump’s voice, of course, is the loudest and most authoritative. The president describes his objectives using a salesman’s best-case superlatives. His economic plan will produce “the highest quality of life” and make the country “the wealthiest and healthiest” of any in the world, he told Congress this month.

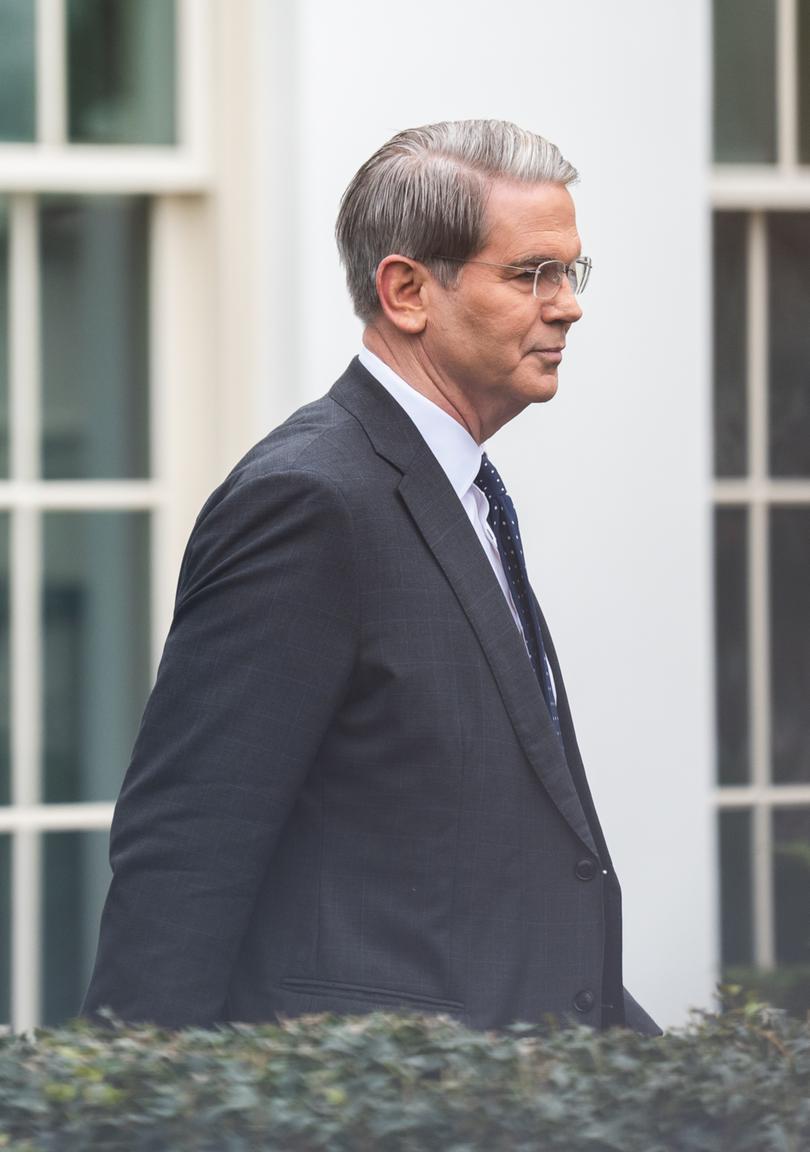

Trump has left it to his aides, particularly Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, to articulate a more complete description of his economic overhaul. In a New York speech this month, the former hedge fund executive said the administration would spur the economy by easing regulations on banks and crafting a new approach to trade and defense burden-sharing.

Stephen Miran, the chairman of the council of economic advisers, likewise wrote late last year that Trump’s second term offered the “potential for sweeping change in the international economic system” through innovative trade and currency policies.

If the administration’s plan succeeds, the $30 trillion U.S. economy would be remade. Already less dependent on the outside world than most major nations, the United States would become even more self-sufficient, producing more of its energy, lumber, steel and computer chips than ever before.

Manufacturing would supplant financialization, creating millions of blue-collar jobs. And government spending, which now accounts for more than one-third of the economy, would shrink, perhaps to the 2000 level of 29 percent of GDP.

“This is a whole new way of thinking. It’s a new economic model,” said Stephen K. Bannon, Trump’s former chief White House strategist.

The president’s radical remaking of the economy addresses real problems: a chronically unbalanced global trading system and unsustainable government finances.

The Chinese government’s policy of subsidizing exports and discouraging consumer spending has flooded global markets with inexpensive products and contributed to a record U.S. trade deficit of more than $1.2 trillion.

At the same time, the Biden administration’s spending on pandemic relief and ambitious industrial policies left the government with an unusually large annual budget deficit of $1.8 trillion - or more than 6 percent of gross domestic product.

Debt held by the public, meanwhile, has soared to $29 trillion, or nearly 100 percent of GDP. Relative to the size of the economy, the government’s accumulated financial obligations are on track to surpass their historic high at the end of World War II.

Trump’s proposed remedies to the economy’s ailments, especially the most widespread use of tariffs in nearly a century, are audacious and, some economists say, unrealistic. Policy execution has been uneven, with the president announcing and reversing tariffs within a single day.

It’s also not clear how tariffs can simultaneously achieve multiple goals, including discouraging the purchase of foreign products, reshoring manufacturing, coercing foreign governments and raising revenue to offset the cost of Trump’s proposed tax cuts. Equally unclear: how the budget gap can be narrowed while taxes are cut.

“What are they trying to do? They don’t have a strategy. They don’t have a clear goal for these policies,” said economist Michael Strain of the American Enterprise Institute, a right-of-center think tank in Washington. “I think what we’re seeing is incompetence.”

On Wednesday, High Frequency Economics, an economic analysis firm, headlined its daily research email: “Global financial markets brace for another day of chaos from Washington.”

After often citing stock market results to validate his first-term performance, Trump and his team now wave off market worries. “The real economy,” not Wall Street, is the administration’s focus, Bessent told CNBC on Thursday.

Some Trump allies interpret such remarks as signaling an overdue change from equating the stock market with Americans’ standard of living. Stock values rose by more than 50 percent under President Joe Biden, for example, but the increase did Democrats little good in the 2024 election.

That may be because stock ownership is tilted toward the wealthy. The bottom three-fifths of U.S. households today own a smaller piece of the stock market than they did when the Berlin Wall came down.

In late 1989, those typical American households held almost 9 percent of all stocks and mutual funds, according to Federal Reserve data. By late last year, their share of the total had fallen by nearly one-third while the portion held by the richest Americans grew.

“The stock market is an absolutely horrible indicator of the health of the working class. There’s very clearly a disconnect between Wall Street and the working-class economy,” said Nick Iacovella, executive vice president of the Coalition for a Prosperous America, a nonpartisan group that is close to the administration.

Even Trump’s allies concede that he cannot complete his promised “revolution” before his term ends in January 2029. It will take several years and cost billions of dollars for companies to build new factories in the United States and to identify domestic suppliers that can replace their overseas vendors.

Likewise, shrinking the mammoth government budget deficit will require painful spending cuts. The administration so far has concentrated on relatively modest, easy-to-mock government grants and what Bessent called “excess employment in the government.”

But the estimated savings claimed by Elon Musk’s DOGE squad have been overstated and marred by errors. And while federal government employment of 3 million individuals is up more than 9 percent over the past decade, it remains lower than when President Ronald Reagan left office in 1989. Federal salaries also amount to less than 5 percent of the government’s outlays.

The budget’s real money is in entitlements and defense. But the president has publicly put Social Security, Medicare and defense off limits.

Completing the transition to the new economy that Trump envisions will not be quick or easy. The president has conceded that it will involve “a little disturbance” while Bessent forecasts a “detox” period, as the economy sheds its addiction to government cash.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick told CBS News recently that the president’s plan was “the most important thing America has ever had” and would be worth implementing even if it produced an early recession.

Initial public reaction to Trump’s second-term policies, however, has been negative.

The S&P 500 index is down 8 percent over the past month and 56 percent of adults in a new CNN poll said they disapproved of the president’s handling of the economy, a greater share than at any time during his first term.

Still, Trump shows no signs of changing course. One reason may be the lack of vocal opposition to the risky course he has selected.

Unlike his first-term team, which was split between establishment Republicans and populist true believers, his current lineup of advisers is unified behind his vision.

“Trump 2.0 is very different from 1.0. Everybody in a senior position was genetically selected to be folks who don’t prevent the president from doing what he wants to do,” said one prominent Republican, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid angering the president.

Even the chief executives of the nation’s largest corporations have shied away from verbalizing their fears that Trump’s tariffs will sever supply chains, cloud investment plans, and shrink profits.

Last week, the president met with corporate leaders assembled by the Business Roundtable. Many are deeply skeptical that global supply chains developed over years can or should be quickly unwound. But the closed-door session with the president was devoid of fireworks.

“They don’t want to get Zelensky-ed,” said the Republican, who attended the meeting, referring to Trump’s public humiliation of the Ukrainian president during a recent Oval Office meeting.

Some business leaders hope to redirect Trump from attacking Canada and Mexico to a more narrow focus on combating China’s trade practices. Foreign companies already see their presence in China as under threat, given President Xi Jinping’s effort to boost his country’s self-reliance. So they are prepared to see Trump erect further trade barriers on Chinese goods, if they can salvage their manufacturing footprint closer to the United States, this person said.

The president’s mercurial nature and limited time in office also make them cautious about dramatic changes in their supply chains or operations. Some are hoping to run out the clock on Trump’s economic revolution.

“The president’s not going to be around forever,” said another Republican business executive. “In four years, you have a different administration.”

© 2025 , The Washington Post