Why political deepfakes are dangerous and what authorities are doing about it

The power to use leaders’ images and put words in their mouth — and electoral authorities are powerless to stop it. Welcome to politics’ new minefield

At first glance, they don’t appear sinister.

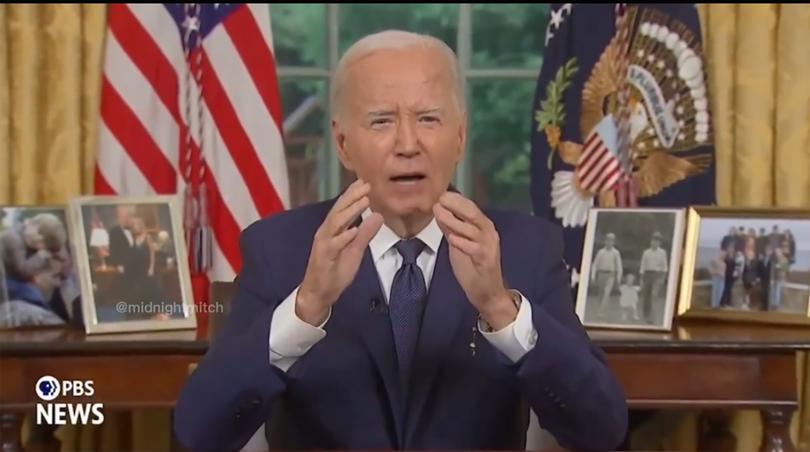

A video of global superstar Taylor Swift holding up a sign: “Trump won, Democrats cheated”; footage of Joe Biden sitting at the Resolute Desk spewing some choice profanities; or a TikTok video of Queensland Premier Steven Miles dancing to a 2000s pop hit.

The more digital literate among us would know right away they were not real, but as artificial intelligence technology becomes smarter, the line becomes blurrier.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Such is the era of the political deepfake.

And, in a year with more elections than ever before, what may appear to be harmless fun risks catching impressionable voters off guard and proliferating mis- and dis-information.

The X video of Swift, Time’s most influential person of last year, has thousands of interactions, although most have rightly identified it as fake.

It carries the community note: “This is a digitally fabricated video of Taylor Swift holding up a banner in support of Donald Trump. Swift has never come out in support of Trump”.

But an impressionable voter, easily swayed by what the superstar says — whether true or not — could miss the clarification and fall for the fake.

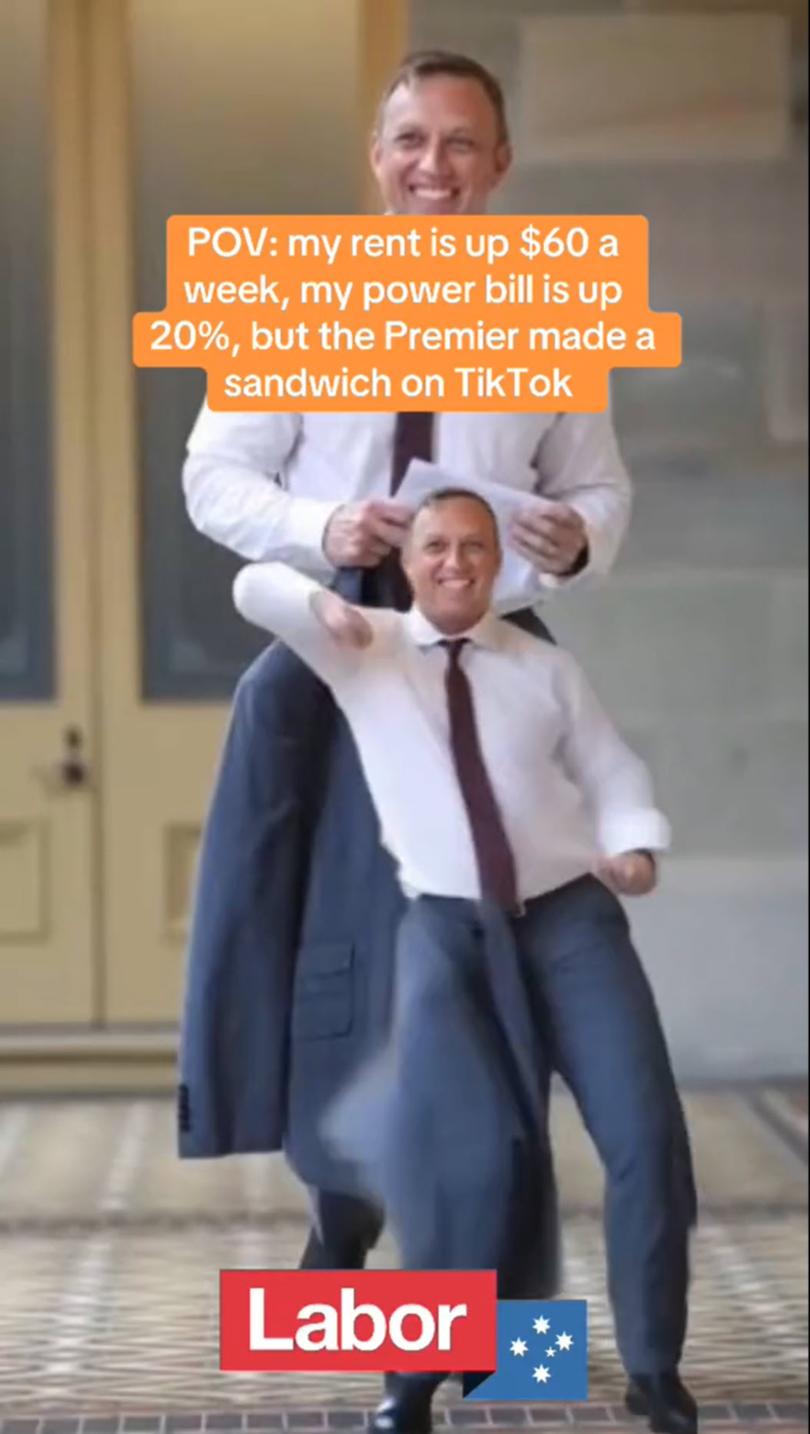

It’s why Mr Miles warned of a “dangerous turning point for democracy” this week, after the Queensland LNP made a video of him dancing alongside the caption “POV: my rent is up $60 a week, my power bill is up 20 per cent, but the premier made a sandwich on TikTok”.

The State Opposition defended its post as clearly labelled as AI, but Mr Miles said that didn’t lower the risk.

“Until now, we’ve known that photos could be doctored or Photoshopped, but we’ve been trained to believe what we see in video,” Mr Miles said on Tuesday.

The latest occurrences are by no means the first.

During the recent Indonesian election a deepfake video “resurrecting” the late President Suharto did the rounds; while in the US earlier this year, there were reports of robocalls featuring an AI-generated voice of President Joe Biden telling voters to skip the primary vote.

While it might be true that the majority of political deepfakes are obviously fake, and often light-hearted, there are growing concerns in Australia about the lack of guardrails surrounding their use, and the risk they pose to the electoral process — especially when used by official parties and campaigns.

As Australian law currently stands, the Australian Electoral Commission has limited scope to protect voters from deepfake videos, photos and audio; because political AI generated material is not prohibited.

That’s to say, if deepfakes are authorised and of a political nature – like the video of Mr Miles – then just like any other election material, they are legal.

The AEC can only act when misinformation is spread about the electoral process.

For example they could only step in if a deepfake video of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese emerged in the days before an election telling people to vote on Sunday, rather than Saturday; or if the commissioner was used in a video advising people to tick boxes or donkey vote, rather than follow the legal preferential system.

We have to create regulation so people can trust what they see and hear,

The Federal government is in the process of legislating new deepfake laws, but only in the context of non-consensual explicit material.

There is mounting pressure on the Government to consider how to police generative-AI more broadly.

Independent Curtin MP Kate Chaney — who, with independent senator David Pocock, has written to government ministers to call for new legislation to be brought before parliament this year to deal with the rising risk of AI — said it was a matter the parliament needed to address “quickly” and “proactively”.

“Part of a functioning democracy is that people are informed, and if you can no longer trust what you see, not only does it mean people can be presented as having said or done something they haven’t, it also provides deniability to people who have said or done something. That really does undermine one of the core tenants of democracy, when there’s already declining trust,” she told The Nightly.

“As soon as we start having to decide when is it appropriate to present someone as having done something that they haven’t and when isn’t it, it gets very grey.

“And sure, it might just be a bit of fun, but it’s then very hard to decide… I wouldn’t be thrilled about any image or any deep fake of me doing something that I haven’t, even if it is something I don’t mind having done.”

She said “alarm bells should be ringing” about the fact political parties were increasingly experimenting, and said even potentially enforcing watermarks or labels would not go far enough.

Greens senator David Shoebridge said while the video of Mr Miles wouldn’t shake the political foundations, it “shows how accessible this technology is, and gives insight into how it could be weaponised in an election campaign”.

“But it’s not just a video of a politician dancing badly that’s a risk, it’s a convincing video of a politician, seemingly saying things that are either deeply divisive, or contrary to their political position that we should be rightly fearful of,” he told The Nightly.

He said there was a collective interest in keeping AI in check.

“I would think ensuring the election isn’t stolen by noxious players deploying deepfakes is not only in the public interest, it’s in the interest of all existing political players,” he said.

He said the Federal government should consider following South Korea’s move, and ban the use of generative AI tools in election materials all together.

Senator Shoebridge said either way, there needed to be urgency in taking strong action before the next election, due by May.

A government spokesperson confirmed Special Minister of State Don Farrell was currently considering how to regulate the use of AI in elections.

“This is not technology that we can stop. It’s not going away,” they said.

“We have to find a way where Australians can have some protection from deliberately false information and content.”

Ms Chaney said whether it was a total ban or not, there was an onus on the parliament to be “very proactive”.

A snap Senate select committee on adopting AI, tasked with inquiring into the opportunities and impacts the technology brings, is due to report back to Parliament by September.

When AEC commissioner Tom Rogers appeared, he stopped short of recommending a total ban on election-related AI content, but floated the idea of political parties and candidates signing a voluntary code of conduct and agreeing to clearly mark generated content.

But even that could take time, and potentially get murky.

AEC spokesperson Evan Ekin-Smyth told The Nightly: “a lot of campaigning information is highly subjective, and there’s nothing to regulate truth”.

“If there was a deepfake video out for example that has the Prime Minister or the Opposition Leader saying something that they didn’t actually say, we don’t have the power to stop it, and we can’t make a public declaration that ‘this is fake, and we are the arbiters of truth’ and stand on a pedestal and tell people… we can’t do that,” he said.

“Largely, it’s the public square that would be discussing it and discussing whether it’s legitimate or not.”

Bill Browne from the Australia Institute this week said the video of Mr Miles showcased the need for effective truth in political advertising laws across the country. He warned that without such laws, it was “perfectly legal” to lie in a political ad.

“What the Steven Miles incident, along with so many others, shows is that the technology has come so far in the last few years, and it’s increasingly within the hands of ordinary people who can create deepfakes quickly and at no cost, with no technical expertise,” he told The Nightly.

“It’s becoming easier to create these kinds of materials, and if used to deliberately mislead, then they could influence election results.”

The Albanese government is expected to introduce legislation as soon as next month to create new powers for an independent regulator to enforce truth in political advertising.

Mr Browne said if the federal laws followed the working South Australia model – which has been in place since the 1980s – it would cover political parties, candidates, lobby groups and other political campaigners, and give electoral commissions greater power to give take-down orders for misinformation.

It would also bring about a court process, which could impose fines.

But given the rise of electoral misinformation spreading online that has nothing to do with official political players, Mr Browne said other regulatory solutions would be needed.

One idea that’s been floated is an “AI commissioner”, similar to how South Korea operates.

Until the AEC is potentially given powers to police truth in political advertising or potentially more muscle to deal with deepfakes, one of its priorities is to run an information campaign, alerting people to different forms of potential disinformation.

“One of the things we can do is what we refer to as ‘hardening the target’, so we run a dedicated campaign in the lead-up to the federal event that alerts people to different forms of potential disinformation,” Mr Ekin-Smyth said.

“We aim to try and make people more digitally literate, and make them aware of the surroundings that they’re in.”

Ms Chaney said as the quality of deepfakes improves “every day”, it becomes increasingly hard for people to discern between authentic content and deepfakes and know what they can trust.

“It’s problematic to put that on the individual. We have to create regulation so people can trust what they see and hear,” she said.