Middle East crisis: The US helped oust Iran’s government in 1953. Here’s what happened

The US has not publicly called for regime change in this Israel-Iran conflict, but over 70 years ago, it played a key role in ousting Tehran’s government.

As President Donald Trump publicly weighs a decision on whether the United States should join Israel in directly striking Iran, some analysts have suggested that Israel’s unstated war aims could include the collapse of Tehran’s government.

Trump, for his part, has ratcheted up his rhetoric, this week demanding “UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER” from Tehran, without detailing what that would mean. He claimed in a social media post that the US knows the location of Iran’s leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, but is not looking to assassinate him - “at least not for now.”

The US has not publicly called for regime change in the current conflict, but over 70 years ago, it played a key role in ousting Tehran’s government - although the historical circumstances were very different.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“It’s forgotten for most Americans. And for the British as well, who were involved in the coup. But it looms in the background of Iranian politics,” said Roham Alvandi, a historian at the London School of Economics.

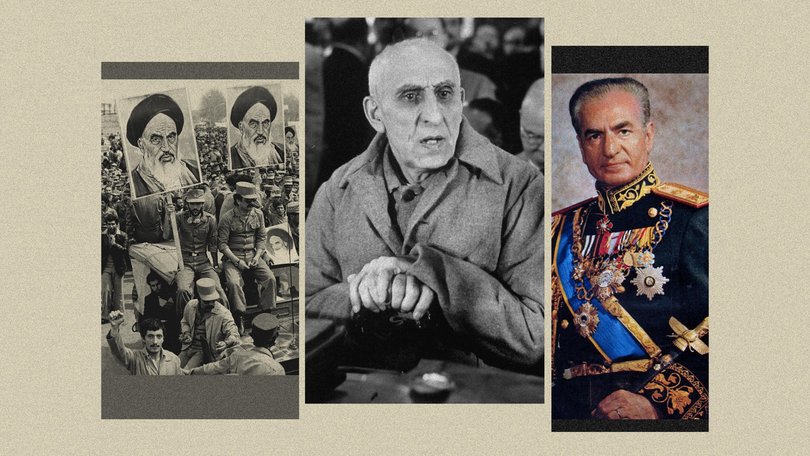

Against the backdrop of the Cold War and Britain’s frustration over its lost access to oil, the CIA coordinated a clandestine operation in 1953 with the British that toppled the country’s democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh.

In his place, Washington helped to reinstall exiled Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, an autocrat who was sympathetic to Western interests and virulently anti-communist. His rule lasted until the 1979 Iranian revolution, but Alvandi said the coup remains a “touchstone” of modern Iranian nationalism.

What led to Iran’s coup d’état?

When Mossadegh was elected to power on a nationalist platform of taking control of the country’s oil assets in 1951, Washington was confronted by a dilemma. The US could support his new government’s nationalists aspirations or side with the British, who were dismayed by the threat Iran’s new leader posed to the lucrative Anglo-Iranian Oil Co (later known as BP).

The wider context was critical. At the time, Washington was deeply unsettled by the spread of communism after World War II, and the British - whose influence in the region was waning along with its dying empire - argued that Mossadegh’s rise was a prelude to even greater Soviet influence in Iran.

The prospect of communism in Iran was anathema to Washington - and in particular to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who took office in 1953.

“Ultimately, they sided with their British allies in the context of the Cold War, because they were afraid that if the oil crisis in Iran wasn’t resolved, then either the Iranian communists or the Soviet Union might seize power,” Alvandi said.

What happened in 1953?

Kermit Roosevelt Jr, the CIA’s top agent charged with orchestrating the coup, was given permission to proceed by his superiors on June 25, months after he was initially approached by British diplomats about the prospect. On July 19 he arrived in Iran through Iraq, where he met with Iranian operatives, communicated with Iran’s exiled shah, and organised support among army officers and street demonstrators.

“America didn’t bomb anything; it was a protracted intelligence operation by the CIA,” said University of St Andrews historian Siavush Randjbar-Daemi, who has researched the 1953 coup extensively. According to Randjbar-Daemi, the coup capped covert CIA influence operations that included the printing of fake Communist propaganda to make the party appear more virulently anti-Islamic than it was.

On August 19, rebels overcame the broadcast studio of Radio Tehran and prematurely declared on the radio that the Mossadegh’s government had collapsed that afternoon - when it in fact hadn’t yet. “After that radio broadcast, it was over,” Randjbar-Daemi said. “It was one of the most effective pieces of fake news in recent history in the world.”

When it appeared certain that the coup had succeeded, Roosevelt wrote to his superiors in a telegram that the shah “will be returning to Tehran in triumph shortly. Love and kisses from all the team.”

In 2013, a declassified CIA internal document publicly confirmed the US involvement: The military coup “that overthrew (Mossadegh) and his National Front cabinet was carried out under CIA direction as an act of US foreign policy, conceived and approved at the highest levels of government,” it read.

What were the consequences of 1953?

Pahlavi returned to power in 1953 as Iran’s monarch, ruling for over two decades as a Western-friendly autocrat. The period coincided with rapid economic growth and urban development for many in Iran, but was also marked by fierce political repression by the shah’s feared intelligence agency, SAVAK.

According to Alvandi, the Shah’s collaboration with the British and Americans to oust a popular nationalist government “fatally wounded” the legitimacy of his monarchy.

“The shah tried very hard for the next 20 years to embody Iranian nationalism, to project an image of himself as a champion of Iran, but he could never get out of the memory of Mossadegh and 1953,” Alvandi said.

His arch domestic rival, the influential religious leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, portrayed him as a Western puppet.

Iran’s oil-based industrialisation caused the economy to boom, but it also led to rampant corruption. When the economy began to sour in 1977, the cracks in his authority only grew.

After months of revolutionary unrest, Pahlavi left Iran in January 1979. Soon after, it became the Islamic Republic of Iran - led by Khomeini.

According to Alvandi, the memory of 1953 - and the shah’s dismal image - cast a long shadow and serves as a tale of caution for any domestic opponents who might contemplate supporting Iran’s foreign adversaries.

“Iranians have a long memory, and as much as they detest the Islamic Republic, they will have a visceral dislike of anyone who is seen to collaborate with a foreign power to hurt Iran and Iranians,” he said.

© 2025 , The Washington Post