THE ECONOMIST: China’s economy is in for another rough year

Bold action in Beijing is needed to turn things around.

Each December China’s rulers gather for their Central Economic Work Conference, where they review the past 12 months and preview the tasks they face in the year ahead. It is a useful exercise, even if you are not a member of the Communist Party’s ruling Politburo.

This year the view in both directions looks bleak. Retail sales in November were only 3 per cent higher than a year ago, even before adjusting for inflation.

Not that there was much of that. Consumer prices rose by only 0.2 per cent over the same period. Both statistics reflect the chronic caution of China’s households. Consumer confidence has never recovered from its collapse during the COVID-19 lockdowns of spring 2022.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.That is the rear view. What about the future?

Exports and manufacturing investment, which have helped prop the economy up in 2024, face the prospect of a new trade war with America.

On the presidential campaign trail, Donald Trump threatened China with tariffs of 60 per cent or higher.

Since his victory, he has said he will impose an extra 10 per cent if China does not do more to curtail the flow of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid made from chemical precursors that often originate in the country.

Some commentators in China hoped the 10 per cent threat superseded the earlier, bigger one. But Mr Trump has said the fentanyl penalty will supplement “additional tariffs”, not substitute for them.

Back-of-the-envelope calculations by Citigroup, a bank, suggest tariffs that high could cut 2.4 percentage points from China’s growth rate, if the government did nothing to cushion the blow.

All of this leaves the folk at the Central Economic Work Conference with a lot of economic work to do. They must revive spending in advance of the trade war and soften the blow to demand if and when tariffs rise.

The past offers some encouragement.

In 2008, during the global financial crisis, China’s export markets in the West collapsed. But its economy still grew briskly, thanks to the government’s rescue efforts.

China back then was a stimulus superpower, able to mobilise vast amounts of demand by calling on state-owned banks to lend and state-owned enterprises to spend. It was also helped by a bubbly property market, which was hard to bottle up, but easy to uncork.

Unfortunately, China’s recent stimulus efforts have been tardy, cautious and ineffectual. It has gradually cut interest rates, mortgage costs and banks’ reserve requirements. But credit demand has remained weak.

To restore faith in the property market, the government has repeatedly urged banks to lend to a “white list” of supposedly viable homebuilding projects. Banks, though, remain wary.

In May the central bank offered up to 300 billion yuan ($62b) in cheap refinancing to state-owned enterprises willing to buy unsold property and convert it into affordable housing. Take-up has been paltry: less than 15 per cent by November 23, according to Huatai, a securities firm.

One reason why stimulus has fallen short in this downturn is that it overshot in the past. The credit boom after the global financial crisis left China with high debts, overcapacity and millions of unsold flats.

Xi Jinping, China’s ruler, came to power in 2012 determined not to repeat the mistake.

When the economy faltered in 2015, he coined a new slogan, “supply-side structural reform”, which emphasised cutting industrial capacity, reducing property inventories and lowering corporate debt — including the liabilities of quasi-corporate vehicles sponsored by local governments.

A similar spirit motivated his later policy known as the “three red lines”, which imposed strict borrowing limits on property developers, pushing many of them into bankruptcy after 2021.

Whatever its virtues, this mindset has hampered China’s efforts to resuscitate the economy in 2024. Although the central government has increased its borrowing, it continued to impose financial discipline on many indebted local governments, which were forced to tighten their belts.

Banks are also cautious about lending to white-listed developers because they worry they will take a hit if the loans turn sour. Under supply-side structural reform, for example, lenders were urged to take equity stakes in corporate borrowers that could not repay their loans.

To cope with the economic risks of the year ahead, China’s rulers will have to prioritise encouraging demand over enforcing discipline. There are welcome signs they now accept that fact.

In November the Ministry of Finance said it would allow local governments to issue additional bonds to replace 10 trillion yuan in “hidden” liabilities, mostly held by financing vehicles set up to evade borrowing limits.

That will lower their borrowing costs. And, as Adam Wolfe of Absolute Strategy Research has pointed out, in 2025 it will free up about 1.2trn yuan they previously devoted to refinancing this debt.

The policy pivot was also evident at the Central Economic Work Conference.

The need to “vigorously boost consumption” and expand domestic demand was listed as the first of nine tasks the government must tackle, elevated above Mr Xi’s signature goal of industrial upgrading.

And after appearing in every official conference report since 2015, the term “supply-side structural reform” was this year conspicuous by its absence.

China’s policymakers have therefore identified the right priority. But how do they intend to achieve it? They may be helped by a nascent stabilisation of the housing market.

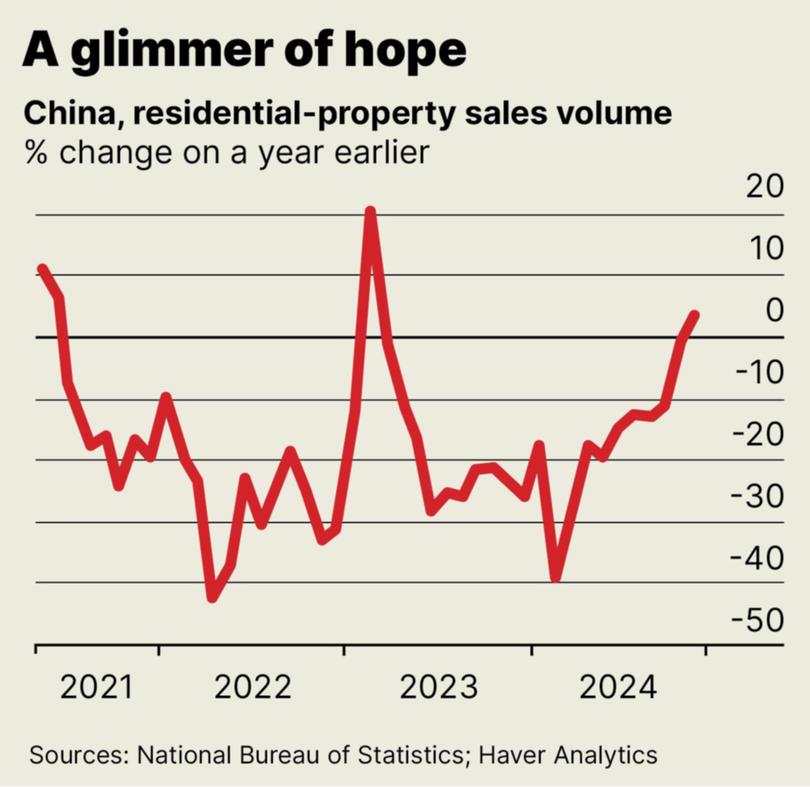

Sales of new residential properties rose a little year-on-year in November, the first increase in over three years, excluding a surge in early 2023 after COVID controls were abandoned (see chart).

Prices also seem to be flattening out.

The price of existing properties in 70 of China’s larger cities fell by less than 0.1 per cent in November, compared with the previous month, according to a weighted, seasonally adjusted average of official figures compiled by Goldman Sachs, a bank.

That may give some measure of confidence to consumers whose wealth is tied up in housing.

To prise open their wallets, cities may experiment with electronic-shopping coupons of the kind that Shanghai has distributed in recent months. These give people a discount on meals, movies, hotels and sports if they spend above a threshold amount.

The government also seems committed to expanding its trade-in program, which encourages households to upgrade their cars, fridges, airconditioners and other gizmos to newer models.

This policy succeeded in raising retail sales of household appliances by over 22 per cent in November, compared with a year earlier. (Overall retail sales were nonetheless weak, thanks to an early start to the “Singles’ Day” shopping festival, which shifted many purchases into the previous month.)

In a further effort to get people to save less, China’s leaders have promised to increase pensions and subsidies for health insurance. Goldman Sachs thinks the government’s broad fiscal deficit could rise by almost 2 per cent of GDP to 13 per cent in 2025.

In the year ahead China needs to lift domestic spending using measures it has in the past neglected. You could call it demand-side structural reform.