The New York Times: Ecuador plunges into crisis amid prison riots and gang leader’s disappearance

The president declared a state of emergency and ordered the military to ‘neutralize’ dozens of gangs. Gunmen stormed a TV studio as cameras rolled.

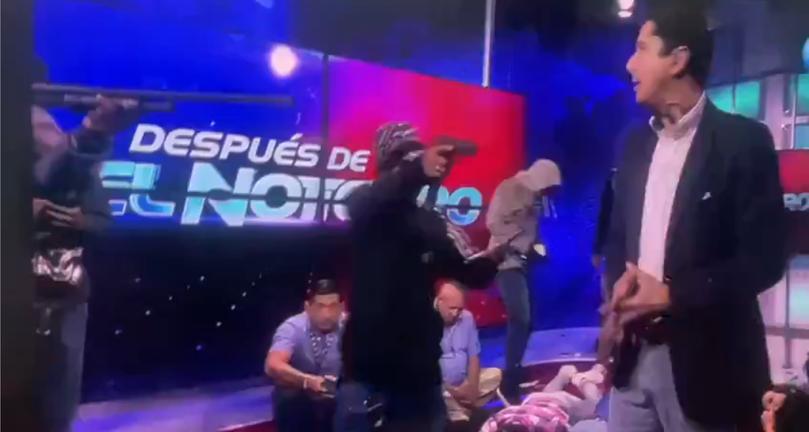

BOGOTÁ, Colombia — Armed gunmen wearing masks stormed a television station Tuesday in Ecuador’s largest city, Guayaquil, taking anchors and staff hostage and exchanging gunfire with police as cameras rolled before the intruders were subdued and arrested.

The televised violence, captured live, erupted as the South American country has descended into chaos this week, with a powerful gang leader disappearing from prison, uprisings breaking out in several prisons and inmates kidnapping and threatening guards.

One of the attackers who stormed the TV station could be heard on air asking to be wired up with a microphone, saying he intended to send a message about the consequences of “messing with the mafias.” Before he could, police intervened. The armed men also forced the anchors and other staff being held hostage to appear in a video asking the president not to interfere.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The police said on social media that they had arrested 13 people after the episode, recovering “weapons, explosives and other evidence.” The hostages were also released safely, the post said.

By Tuesday afternoon, at least eight people had died and two others had been injured in violent episodes in Guayaquil, according to the city’s mayor, Aquiles Álvarez, who held a news conference alongside the chief of police. Authorities also said five hospitals had been overtaken.

Explosions, burning vehicles, looting and gunfire were also reported across the country, and authorities announced that a second major gang leader and other inmates had escaped from another prison.

Ecuador’s president, Daniel Noboa, declared an internal armed conflict on Tuesday, and ordered the armed forces to “neutralize” two dozen gangs, which he described as “terrorist organisations,” according to a post on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Shops, schools, government offices and buildings were shut down. Workers were sent home, and streets in Quito and Guayaquil were jammed with traffic.

“It was chaotic, as you can imagine,” said Carolina Valencia, who was visiting family in Guayaquil from New York. “There was traffic everywhere because people just wanted to get home. The buses weren’t fully operating, so people were jumping on the pickup trucks that are open in the back.”

“There was a lot of desperation,” she added. “Since this gangster disappeared, everyone has been in constant fear.”

Noboa, who has prioritized restoring security to a country awash in gang violence fuelled by a flourishing drug trade, had earlier declared a state of emergency and deployed more than 3,000 police and military officers to search for the escaped gang leader, Adolfo Macías.

The 60-day declaration imposes a nationwide overnight curfew and allows the military to patrol streets and take control of the prisons.

“The time is over when drug-trafficking convicts, hit men and organized crime dictate to the government what to do,” Noboa said in a video announcing the state of emergency Monday, adding that it was necessary for security forces to take control of Ecuador’s prison system.

Macías, who is the head of Los Choneros gang and is better known as “Fito,” disappeared Sunday from an overcrowded prison in the coastal city of Guayaquil, from which he has long overseen his group’s operations.

The government had ordered the transfer of high-profile convicts, including Macías, from the cells where they have been running their criminal rings to a maximum-security facility. That decision, prison experts said, may have led to the escape of Macías and the prison uprisings.

Some security experts believe that as many as one-fourth of the country’s 36 prisons are controlled by gangs. Noboa has vowed to retake control of the prisons, which have become both gang headquarters and recruiting centres.

Last week, he announced that he was seeking to hold a referendum on security measures, including harsher sentences for crimes like murder and arms trafficking, and expanding the role of the military.

Noboa, the centre-right scion of a banana dynasty, took office in November after an election dominated by worries about safety and the economy. Violence has spiralled in recent years as gangs have battled for control of lucrative drug-trafficking routes that transport narcotics to the United States and Europe.

Those fears were amplified by the assassination on the campaign trail of another presidential candidate, Fernando Villavicencio, who had said not long before his killing that he had been under threat from Los Choneros.

Macías is perhaps the most well known of the gang leaders running drug operations from behind bars, and his group is believed to have been one of the first in Ecuador to forge ties with powerful Mexican cartels.

Macías, who is serving a 34-year sentence for crimes that include drug trafficking, escaped from prison once before, in 2013. He became the leader of Los Choneros around 2020 and has presided over the gang’s activities from his cell in the Guayaquil prison, part of a compound that holds around 12,000 inmates.

After Villavicencio was assassinated last summer, Macías was briefly moved to a maximum-security wing in the same compound. But his lawyer appealed, and a judge ordered Macías to be transferred back to his preferred spot in the prison in Guayaquil, which serves as the Choneros’ base.

He celebrated by releasing a music video in the style of a “narcocorrido,” a genre originating in Mexico that glorifies the violent feats of drug traffickers.

Last month, Noboa, promoting his plans to tackle the country’s prisons, said he would start with measures such as cutting off Macías’ access to power outlets and routers. “You can see on YouTube that Fito’s cell has four outlets, more outlets than in a hotel room,” Noboa said.

Macías was found missing from his cell during a sweep for contraband. His disappearance came as he and other high-profile criminals were scheduled to be sent to the maximum-security prison, according to officials.

A top government official suggested this week that Macías may have learned of his imminent transfer through a government leak. “That would be very serious,” said the official, Esteban Torres, because “it would mean that there is rot at the highest levels of government.”

Securing Ecuador’s prisons is vital to making sure efforts to root out corruption are effective, said Will Freeman, a fellow for Latin America studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“You need to make sure that when you actually send people to prison for money laundering or working in complicity with organized crime as public officials, that the punishment is meaningful and that they’re not just continuing to operate criminal rings from jails,” he said.

He said a state of emergency could help stabilize the prisons, since the entity tasked with running the prison system had failed to control gangs, but that it was not a long-term solution. He noted that Noboa’s predecessor had repeatedly imposed similar measures.

“Obviously they didn’t really durably improve the situation,” he said.

Jorge Núñez, an anthropologist who has studied Ecuador’s prison system for years, said Noboa was not doing anything dramatically different when it came to the penitentiary system.

“It’s a mix of improvisation, and basically doing the same thing,” said Núñez, who said the previous government had turned the prisons over to the police, who had overlooked “the growth and excessive empowerment of prison gangs.”

The privileges extended to cartel leaders increased over time, he added.

Sweeps of prisons have revealed not only extensive caches of weapons and electronics, but also pigs, roosters and a cockfighting ring.

Monday night, as the first curfew approached, the streets of Quito, the capital, were quickly deserted. Only police cars and ambulances could be seen, in a quiet reminiscent of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

“The curfew affects us directly,” said Junior Córdova, a restaurant owner in Quito. “We had a great beginning to the year, but that’s not looking so good now, because people are starting to feel scared.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2023 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times