Why Jacinda Ardern made a deeply intimate documentary about her marriage

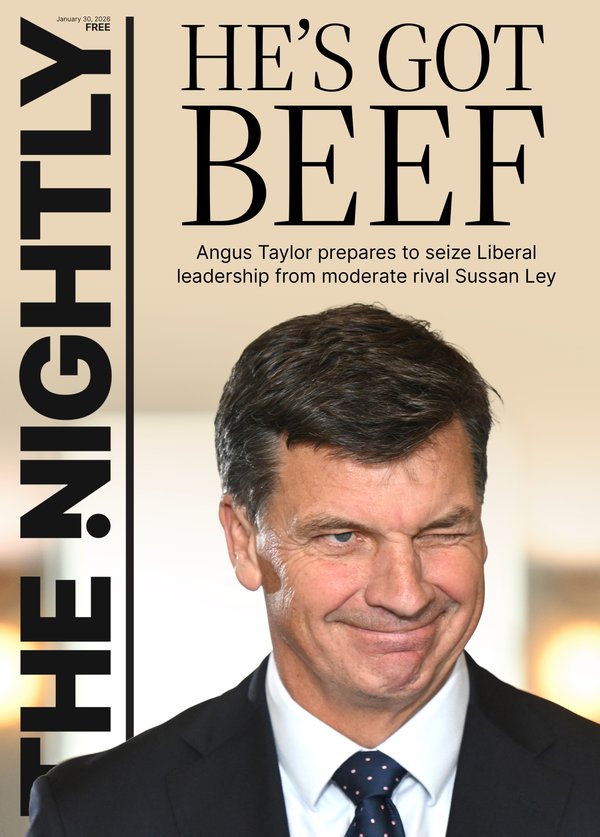

Former New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern is the subject of a new film, Prime Minister, in theatres Friday, which aims to humanise politicians.

Somewhere on the cutting-room floor of Prime Minister, a new documentary about Dame Jacinda Ardern’s fraught 5½ years leading New Zealand through crisis after crisis, is a montage of her repeatedly asking husband Clarke Gayford to please get that camera out of her face.

“Someone would have just seen a lot of me telling him to go away,” Ms Ardern says, laughing, over a squeezed-in lunch of tomato soup at DC’s Conrad Hotel before speaking to a rapt crowd about her recent memoir at the historic synagogue Sixth & I.

In person, Ms Ardern, 44, is warm and disarmingly down-to-earth. She styled her hair herself, now a few shades lighter than it was in the film. Her aide says that she’s travelling with “a far bigger entourage” than usual - three people, including him. In the car, she offers everyone dark chocolate from New Zealand, and then insists they’re not taking big enough chunks. But there are also hints that she’s still living with some trauma from her time as prime minister. She pre-signed all her books and only takes questions at the event that were submitted in advance. She’s ushered in and out of the room in record time by several large security guards.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Stepping off the train in Washington, she says the first thing that hit her was the city’s sheer amount of history. “Obviously this is an incredibly difficult time, and a period where it feels like the US is retreating from being out in the world,” Ms Ardern says. “But that is not forever. This is a place that reminds you that history is much longer than this moment in time.”

When Mr Gayford started asking her to process her raw emotions about her biggest moments as prime minister on camera, Ms Ardern went along with it because she figured no one would ever see it. That is, until the couple handed over 300 hours of tape to documentarians Michelle Walshe and Lindsay Utz following Ms Ardern’s shocking January 2023 resignation as New Zealand’s prime minister. Her voice trembling, she’d said she was stepping down because “I no longer have enough in the tank” to give the job what it required.

“You might ask why on earth would we do this and put this much of ourselves out on screen,” Mr Gayford, 48, says. “And the goal that we wanted to achieve is just trying to humanise politicians. (They’re) just people, by and large, trying to make the best decisions that they can.”

A widely known radio DJ and host of a TV show he created called Fish of the Day, Mr Gayford says he was simply operating on instinct when he first pulled out a camera to document Ms Ardern learning she’d become prime minister in 2017 at age 37, having found out days earlier that she was pregnant. And then he kept finding himself in the craziest of situations. (The film also features audio diaries that Ms Ardern recorded for New Zealand’s national library.)

In what would be a major scandal in the United States but barely made a ripple in New Zealand, Ms Ardern and Mr Gayford weren’t married when she was sworn in. At a news conference announcing her pregnancy, Mr Gayford joked that he loved that they’d done everything backward: “We bought a house together, then we’re having a baby, and we’ll see (about marriage).” (They got engaged during her first term, with her bodyguard standing by, but didn’t manage to pull off a wedding until after she left office.)

There’s a moment early in the film (in theatres Friday), when Mr Gayford apologises for prodding Ms Ardern to reflect on her election win while she’s sitting on an unmade bed, trying to get gunk out of her eye.

“You’re not going to force me to process this, this morning,” she says, smiling but curt. “I don’t have time.”

“Well, I’m conflicted because as your partner, I want to support you, but as someone who’s trying to film this, it would be nice to know what’s going through your head, I guess,” Mr Gayford says, with a nervous chuckle.

“I’m not doing this right now,” Ms Ardern says, giving him a death stare before immediately leaving the room.

Mr Gayford was there at the United Nations General Assembly when Ms Ardern was trying to figure out where to breastfeed in a building set up for male leadership, and by her side during violent pandemic-era anti-vax protests calling her “Jabcinda” and waving signs depicting her as Hitler.

“Sometimes I felt like the worst partner in the world,” Mr Gayford says over Zoom. He’s speaking from Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he is being an objectively pretty great partner and taking care of their daughter Neve, who turns 7 this month, while Ms Ardern is on book tour.

Mr Ardern, whose memoir, A Different Kind of Power, is a treatise about empathetic leadership and kindness, has become improbably famous in the US for the leader of such a small country on the other side of the world.

She took office just nine months after President Donald Trump started his first term and quickly became a fantasy draft pick for many who dreamed of a polar-opposite style of governance. In 2019, when a terrorist opened fire on two Christchurch mosques, killing 51 in the deadliest mass shooting in the nation’s history, she wore a headscarf to tearfully embrace mourners, then pushed through a ban on semiautomatic weapons less than a month later.

In March 2020, she made the controversial decision to shut down New Zealand’s borders and institute one of the strictest lockdowns in the world, effectively containing COVID-19 to such an extent that the country was able to reopen schools and gather at outdoor concerts. By the time they reopened borders in mid-2022, 90 percent of the population had been vaccinated.

It would usually take Mr Gayford until 11 at night to work up the courage to ask his partner to relitigate whatever global event she was dealing with on camera - “She couldn’t go anywhere, she was trapped,” he says, laughing - which is why so much of the film features Ms Ardern in her pyjamas.

“I always joke that there [were] three of us in the relationship: me, her and the cabinet papers, because they would just be spread across the bed and everything,” Mr Gayford says. “She was very generous in the sense that she at least attempted to humour me.”

Ms Ardern says she ultimately wanted to do the movie as a tribute to Mr Gayford, who put his career on pause to take care of Neve while Ms Ardern ran the country. “Clarke’s amazing. He’s a kind of quiet hero behind the scenes,” Ms Ardern says. And she wanted to show women how much help she needed to do everything she’s done. “They shouldn’t be taking everything on,” she says.

It is Mr Gayford’s home videos, of course, that make “Prime Minister” so incredibly intimate - a rare glimpse of a world leader at her most vulnerable, often tearing up as she tackles the weight of perhaps the most difficult premiership in New Zealand history - while a baby crawls around on her desk.

“Be nice to see you sometime,” he says, almost pleading, off-camera.

“Yup,” she says, not even looking up from her paperwork.

We see Ms Ardern chiding Mr Gayford about eating her pregnancy biscuits (“Are you worried about your milk production? Hormone stores?”); Mr Gayford telling her she looks like “a real ratty porcupine” as she lies in bed getting acupuncture for her swollen feet; and Ms Ardern’s mother’s honest reaction when told the baby’s name. “Neve? That’s different.”

On camera to Mr Gayford, Ms Ardern opens up about the terrible sense of failure she feels because she can’t produce enough breast milk. We see her pumping in the motorcade and Mr Gayford changing Neve’s nappie, as Ms Ardern meets with Mr Trump at the UN General Assembly or with the president of Morocco. She delivers sharp criticism of Boris Johnson for letting COVID run rampant, as Neve runs around their living room.

Ms Ardern and Mr Gayford - who moved to the Boston area in 2023 after Ms Ardern was offered two Harvard fellowships - met in October 2012, back when she was a junior member of Parliament and he was the famous one. A year later, he emailed her.

“I had a grievance and I reached out to my local friendly list MP, who happened to be her, and offered to see if there was some way I could help with her campaign. We were friends for a long time first,” Mr Gayford says.

Ms Ardern had been raised Mormon and had mostly dated others in the faith. As an MP, she couldn’t go on dating apps, and two boyfriends had already split up with her over her career, one via text. “But then came Clarke,” she writes in her book.

When they got together, of course, neither of them knew she’d become prime minister. But Mr Gayford (as well as Walshe) says he had no doubt she was going places. “Oh, I think everyone around Jacinda believed in her abilities, perhaps more than she did,” he says.

The realities of dating a PM were more unpredictable. As soon as she took office, Ms Ardern lost access to her cellphone. Mr Gayford suddenly had to figure out how to talk to her when every 15-minute block of her calendar was reserved for national business.

The film shows a couple who’s figured out a division of labour under extraordinary circumstances, but Mr Gayford says they never discussed who would step back from work. “It was a case of just rolling your sleeves up and getting it done. And I never thought that that was anything other than what you do when you’re in a relationship, right? You divide and conquer to get through whatever it is through the day,” he says.

The part of the film that made Ms Ardern cry at its January Sundance premiere, just three days after Mr Trump’s inauguration, is a moment from 2021 when she has to leave behind a wailing Neve to manage a COVID outbreak. Festival-goers gave the movie a rare standing ovation.

Ms Ardern, though, is a controversial figure in New Zealand, where violent protests broke out over the country’s sluggish recovery following her COVID lockdowns - which clearly rattled the PM and her family, as shown in the film. Immediately following the Sundance premiere, the movie’s IMDb page was bombed with one-star reviews from people who’d never seen it.

Her resignation had come amid tanking poll numbers, and Labour lost nearly 50 percent of the seats it had held in 2020, prompting speculation that she was simply getting out before an inevitable defeat.

“She mentions in one of the audio diaries that overseas she’s celebrated and at home she’s criticised, and you do see and feel that,” says Mr Utz, who pored through hundreds of hours of news clips and protest footage during the edit.

“I’d also like to add, though, that there’s some good old-fashioned misogyny thrown in there as well,” Mr Utz continues. “It’s really hard to imagine that, if she were a man, (she’d get) the kind of really cruel signage outside her office during the protests. They were hanging nooses from the trees. At one point, a man screams, ‘I’m not going to take commands from a woman in skirt on a power trip’.”

Ms Ardern never mentions Mr Trump’s name if she can avoid it, preferring to talk in generalities in a politic way. “That’s deliberate, and I’m happy to tell you why,” she says. “One of the things I (often) talk about is that we are understandably placing a lot of emphasis on a very particular type of leadership style and leader, and I want to spotlight the alternative.”

In the film, Ms Ardern talks about the cumulation of factors that led to her resignation. Threats to her family. A difficulty balancing motherhood and the worst job in politics. Burnout. Their stint in Cambridge was meant to last three months. They’ve stayed two years. The change of pace felt good. Ms Ardern loved that it’s a walkable city with strong communities, just like home in Auckland. Writing her book was a form of therapy, not, as one might suspect, a toe-dip back toward elected office.

“The only place I can do that is New Zealand, and I’ve very clearly made the decision that my time is done, and I don’t regret that,” she says. “I miss the job and I miss the people, but I don’t regret the decision.”

She’s really not planning to run for anything?

“Oh my gosh, no!” she says. “No, no. Hard no.”

They’re off to the UK next, where Ms Ardern has accepted a university position similar to the one she held at Harvard. She’s still in the political realm, working with the Christchurch Call, a foundation dedicated to fighting violent extremism, and running a fellowship on empathetic leadership, trying to nurture the next generation of men and women who want to lead with kindness. “We will get back to New Zealand eventually,” Mr Gayford says. “That has always been on the cards.”

When asked if she decompressed after stepping down, she bursts out laughing. “The responsibility, that was just instant. It’s just - whoosh - and it’s gone,” she says. “But the slowing down, that I haven’t done yet. I’m looking forward to it.”

© 2025 , The Washington Post.