Mackenzie’s Mission: Emeritus Professor Nigel Laing AO paves way for nationwide genetic carrier screening

A groundbreaking Australian study has helped prospective parents discover whether they might pass on a severe genetic condition to their children.

A groundbreaking Australian study has helped prospective parents discover whether they might pass on a severe genetic condition to their children.

Mackenzie’s Mission is Australia’s first genetic carrier screening program, testing 1300 genes associated with 750 severe genetic conditions.

The major study, published today in The New England Journal of Medicine, makes the case for a more accessible, government-funded screening program for Aussies looking to start a family.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.More than 9100 couples were screened to see if they had an “increased chance” of having children with one or more of the 750 childhood-onset conditions.

Of those tested, 175 couples — about one in 50 — were revealed to have this risk.

These couples have a roughly one in four chance of having a child with the associated condition.

About three quarters of affected couples used the information to inform their decisions about having children, including using IVF and selecting embryos unaffected by the condition.

The Federal Government has reproductive carrier screening for just three genetic conditions on the Medicare Benefits Schedule — spinal muscular atrophy, cystic fibrosis and fragile X syndrome.

But the study showed that 80 per cent of the affected couples had an increased chance of bearing children with other severe genetic conditions.

It’s placed large-scale, government-funded preconception screening firmly in the sights of researchers at the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, one of several labs that led Mackenzie’s Mission.

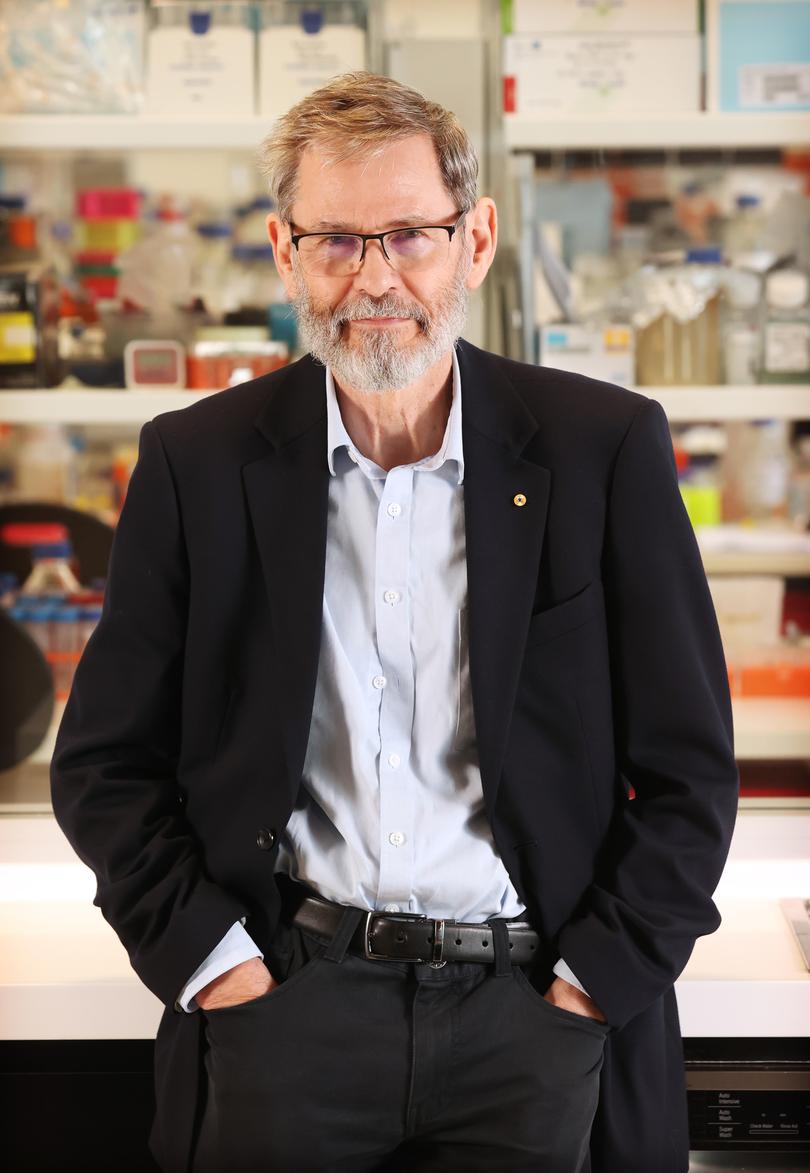

Emeritus Professor Nigel Laing, from the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, led the study, starting in 2015 by recruiting Professor Edwin Kirk from the University of NSW, and Professor Martin Delatycki from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute as co-leads.

At the same time, Rachael and Jonathan Casella were lobbying politicians in Canberra to introduce free reproductive genetic carrier screening after losing their baby girl Mackenzie to spinal muscular atrophy at just seven months old.

The Casellas had never heard of the rare neuromuscular condition, which causes motor neurons to deteriorate and waste, and had no idea they were both genetic carriers for it. There is no cure.

Then Federal health minister Greg Hunt awarded $20 million to the project in 2018 — dubbing it “Mackenzie’s Mission”.

“(Mr Hunt) said we had to take it to every corner of Australia to show that we could make it available to any couple in Australia who wanted to use it, and to all socioeconomic levels,” Professor Laing said.

Mackenzie’s Mission has shown the value in making widespread genetic carrier screening freely accessible for family planning, Professor Laing said.

“What we showed ... is that with the genes we screened, we identified five times more high chance couples than would be detected by just screening for those three conditions,” he said.

About half a dozen genetic counsellors across the country helped affected couples to understand their options moving forward.

Sam Edwards, who coordinated the program across WA, Queensland and South Australia, said there were a few options.

Couples could test embryos during IVF and choose to implant unaffected embryos, have a natural pregnancy and test at 12-16 weeks and then decide whether to continue the pregnancy, or they could fall pregnant and not know.

“Some of the conditions that we tested for, if you know about it early enough, you can get treatment in place and the prognosis can actually be really good,” Ms Edwards said.

For Perth’s Kelly and Tyler Binnington, genetic screening prior to the birth of their son Charlie may have helped prolong his life.

After an uncomplicated pregnancy with their first child, Ella, their little boy Charlie was born in September 2022 via planned C-section.

“As soon as they pulled him out, they noticed he had laboured breathing, so they (nursing staff) took him down to the NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) and said that’s all normal for a C-section baby,” Mrs Binnington said.

“Tyler went with him, I went into recovery, and then he never came back. (Charlie) got admitted to PCH straight away.”

He was in the NICU for 12 days, staff didn’t know what was wrong.

After a follow-up appointment, they were sent for further testing before he was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy — an enlarged, weakened heart.

Charlie was readmitted, the couple had a rapid genetic test, but miscommunication meant they were sent home before getting the results.

“That was just after the cardio team said there was nothing they could do (for Charlie’s heart),” Mr Binnington said.

At home, getting ready to say their goodbyes, the couple finally received the correct diagnosis.

Charlie had Barth syndrome, a rare disorder that affects one in 400,000 births and causes weakness in the heart, muscle system and immune system. There is no cure.

Mrs Binnington described the initial news as a “kick in the guts”, but said she was “hopeful because we had a diagnosis, which meant that he could be treated, and there was a prognosis”.

But at four months old, Charlie contracted a common cold and died.

While reproductive carrier screening would not necessarily have saved Charlie, Mackenzie’s Mission aims to reduce the wait for a diagnosis for families.

The Binningtons have launched the Charlie’s Angels Foundation in their son’s name, offering support to bereaved families who have experienced pregnancy, stillborn and infant loss.