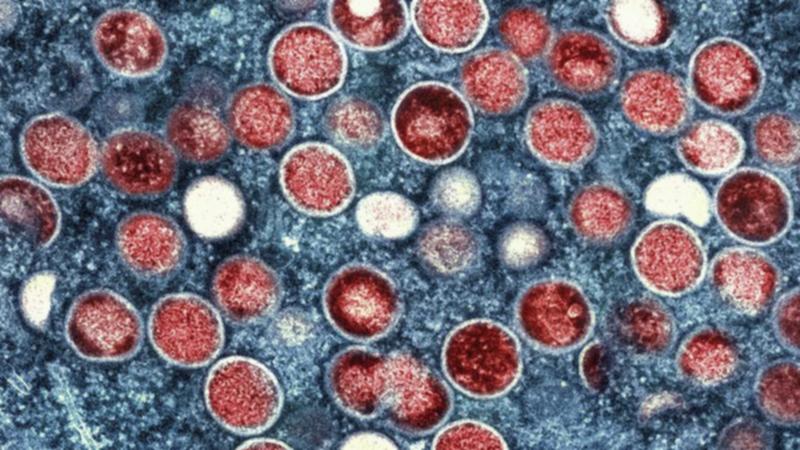

Mpox outbreak: Should I be worried about mpox? Here’s what you need to know about the health emergency

Mpox is not a new phenomenon, but its rapid spread through Africa has sparked enough concern to trigger the World Health Organisation to pull the alarm. Here are five things you need to know.

An outbreak of mpox — formerly known as monkeypox — in Africa has prompted the World Health Organisation to declare the virus a global public health emergency for the second time in two years.

According to an Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention briefing, 34 countries in Africa were either reporting infections of the rare mpox virus or were considered “at high risk”.

The most severe outbreak is in the Democratic Republic of Congo, with more than 14,000 reported cases and more than 500 deaths to mpox since the start of 2024 — a toll that already matches that of all 2023 — including cases in provinces previously untouched by the virus.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Mpox has also been detected for the first time in the neighbouring countries of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda, adding to experts’ alarm.

And while mpox is not a new phenomenon — it was first detected in a monkey in Denmark in 1958 (hence the name) — its detection beyond endemic countries in Central and West Africa and at such high rates has sparked enough concern to trigger the World Health Organisation to pull the alarm.

Why are mpox cases surging?

Mpox was first detected in a human in DRC in 1970 and historically has been transmitted by contact with an infected animal, whether through bites, scratches, its bedding, or by handling or eating infected meat.

There are two genetic groups (or clades) of mpox, known as clade I and clade II. The latter is endemic to West Africa and drove the 2022 global outbreak. It is less severe and less deadly than clade I, which is endemic to Central Africa.

Trouble is, scientists have detected clade I and a new variant, clade Ib, in the recent surge of cases in the DRC and surrounding nations; both of which can be spread by close contact with an infected human.

Most cases of clade Ib in adults is being spread through sexual contact (83.8 per cent of cases) but also through other physical and face-to-face contact, or via contaminated bedding or towels. Sex workers, in particular, made up a high proportion of those infected in this latest surge.

More children are being infected, too, accounting for more than 70 per cent of mpox cases and 85 per cent of deaths in the DRC — reflective of their weakened immune systems, perhaps due to malnourishment, or not having the protection of a smallpox vaccine that older generations may have received.

Is mpox deadly?

Mpox is related to the virus that causes smallpox, belonging to the same Orthopoxvirus genus group of diseases that cause rashes, bumps and blisters on the skin that can fill with pus, crust over, and eventually heal.

Its symptoms are also quite similar to smallpox: those infected may have a rash, fever, sore throat, headache, muscle aches, back pain, low energy, and swollen lymph nodes. Signs of infection can begin within a week or up to 21 days after exposure.

An mpox rash appears as a flat sore possibly on the hands, feet, face, mouth or throat, groin and genitals or anus. It can be itchy or painful but as it heals the lesions dry, crust over and fall off.

But unlike smallpox, which was eradicated by the 1980s, it causes a mild illness but rarely death. Smallpox was tatal in about 30 per cent of cases. Clade I and II of mpox, according to the CDC, are fatal in 11 per cent or 4 per cent of cases, respectively.

Is there a vaccine for mpox?

There is a vaccine, but not enough of it. Africa CDC says it needs 10 million doses for the population, but only 200,000 doses are available.

According to Al Jazeera, the DRC’s minister of health has authorised doctors to administer the vaccines that are available in the highest-risk areas, and officials are in talks with other countries, including Japan, to procure more vaccines.

By declaring mpox a “public health emergency of international concern”, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has triggered an energy use listing for two vaccines, which allows organisations like UNICEF to procure them.

There is a vaccine available in Australia called JYNNEOS that is free for eligible groups — including gay and bisexual men, sex workers, and these groups’ partners.

The fast rollout of vaccines in 2022, particularly in developed countries, led to a rapid decline in transmission.

And while there is still a risk of infection to the virus that causes mpox even with a vaccine, those who got the jab may only experience mild symptoms.

What does the WHO declaration mean?

The WHO has effectively issued an international call to arms with its declaration, experts say.

Head of the HIV Epidemiology and Prevention Program at the Kirby Institute, UNSW, Andrew Grulich said it’s “best opportunity we have to prevent the global establishment of mpox”.

“The spread of new, possibly more lethal variants in more African countries is worrying, and has the potential to lead to global spread,” Professor Grulich said.

“All infectious disease pandemics are different, but they are also the same. The key similarity is that early highly targeted action using effective tools can prevent global spread and the global establishment of endemicity.”

There have been more than 14,000 cases and 524 deaths in Africa this year due to mpox and more than 96 per cent of all cases and deaths are in the DRC.

Africa CDC had already announced on Tuesday that mpox was a public health emergency, with the organisation’s director general Dr Jean Kaseya saying it was “not merely a formality” but a “clarion call to action” to eliminate the virus.

Dr Kaseya has suggested the continent will need about $4 billion to fully address the epidemic.

The WHO’s declaration may accelerate access to testing, vaccines and treatments in the affected areas as well as kickstart responsible education and prevention campaigns around the virus.

Should I be worried here in Australia?

It may seem a world away in Africa, but there has been a re-emergence of mpox in Australia in 2024.

So far, there have been 241 confirmed cases of mpox this year compared to just 26 cases in 2023. There was a total of 144 mpox cases across Australia in 2022 — all males, most commonly aged 30 to 39.

This year, Victoria and NSW have reported the most mpox cases, 108 and 93 cases respectively. All but one of the 241 confirmed cases of mpox are in males.

No doubt those travelling to Africa would need to take increased caution.

The Australian government has warned would-be travellers to “reconsider your need to travel to the DRC”.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Smart Traveller site updated its travel warning in July, citing the “ongoing risk of infection from Ebola virus and Mpox”, as well as wider unrest.