THE NEW YORK TIMES: They Promoted Body Positivity. Then They Lost Weight

Celebrities, models and influencers who once celebrated their curves are grappling with how to discuss their smaller bodies, while their followers feel as if they’ve abandoned the causes they used to champion.

Tianna James used to love looking at the photographs Dronme Davis posted of herself on Instagram. Davis, a plus-size model, included pictures from her modeling campaigns alongside selfies of her stretch-marked stomach with captions like “fat belly saggy tits Sunday.”

For James, 22, Davis’ feed was a revelation. “I wanted to feel comfortable in my body, and she was like me in so many ways, so it made it easier to be myself,” James said. “If I could find this person so beautiful, and she was bigger, I could find myself beautiful, too.”

Davis gained a following through posts that criticised diet culture as she built a career as a curve model — she wore up to a size 16 or XXL — most prominently for Dôen, a California fashion brand known for floral prairie dresses typically worn by more willowy women. Her feed was a running commentary on the unrealistic expectation to conform to a thin ideal: “A flat stomach won’t change your life” and “It’s so exhausting being afraid and ashamed of parts of ur body.”

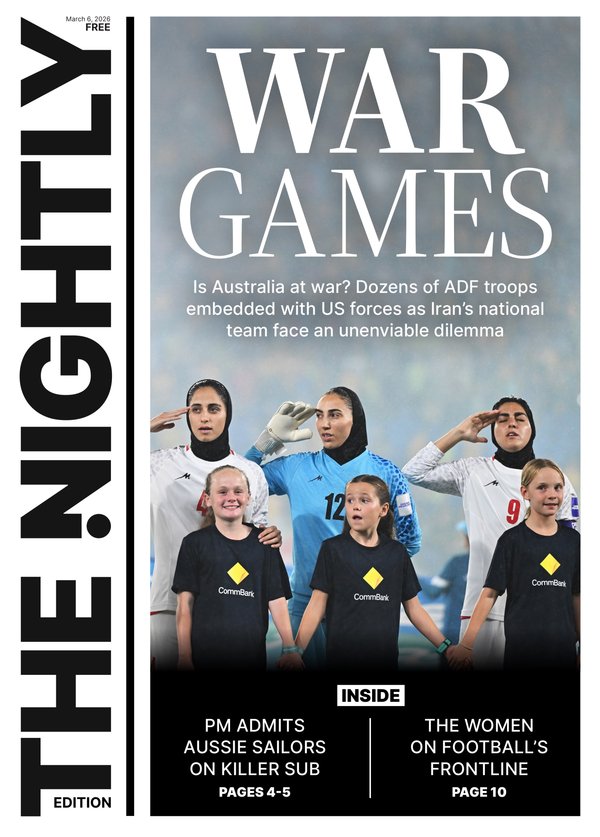

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Then, over just a few months, Davis shrank.

She still posted the artsy selfies James loved, but photos of soft belly rolls were replaced by sharp cheekbones and clavicles. She continued to write in her confessional style, sharing her feelings about everything from constipation to career insecurities. But Davis stopped posting her habitual rants against fatphobia, and she didn’t explain why or how she had lost so much weight.

To James, Davis’ silence felt like a betrayal.

“It made me feel like she was being dishonest with her community,” James said. “I don’t want to say it was owed to us, but it was such a drastic change.”

The body positive movement has recently faltered in a cultural moment where thin is back in (though some argue it never really left), thanks in part to the rise of new drugs like Ozempic that are being used for weight loss. Celebrities, models and influencers like Davis who once celebrated their curves are grappling with how to discuss their smaller bodies, while their followers feel as if they’ve abandoned the causes they used to champion: encouraging people to challenge weight stigma and to accept themselves as they are.

‘She Won’t Cop to It’

Davis said that she had long agonised over how to publicly address her weight loss. Despite what some of her followers suspected, she wasn’t on Ozempic. The truth — that she had relapsed into the disordered eating practices that she had struggled with throughout her life — was hard for her to admit, even to herself. How had she succumbed to the same pressures she had warned her nearly 100,000 followers about?

“The only thing people are going to be OK with is a very detailed explanation, which is not something I can write in a caption,” the 24-year-old said by Zoom from her bedroom in the woods in Mendocino, California, where she lives with her mother.

She didn’t want to beat herself up for relapsing, but she also empathised with followers like James.

“I gathered all these women to follow me because I was going to be inspiring and make them feel empowered,” Davis said. “How can I still expect their attention and support?”

Davis grew up in a small town in Northern California. She put herself on a diet by the time she was 10, after she began to develop breasts. Her weight fluctuated, but when she was thinner, she said, she could fit into the Abercrombie miniskirts that her friends wore, and teachers took her more seriously.

She was discovered through her Instagram shortly after she graduated from high school, and soon landed a job as Dôen’s first curve model. She has since modeled for much bigger brands, including Levi’s, Sephora and The North Face, but she became a familiar fixture on Dôen’s website: The designers have called her their “longtime muse” and named a pair of jeans that came in extended sizes after her.

As Davis grew up online, it felt natural to post about all the facets of her life — not just her modeling, but her racial justice activism, her artwork and her evolving relationship to her body. Looking back, she said, in her passion to share her own learning process, she unintentionally positioned herself as an expert on body acceptance when that was not the case. It was a humbling experience and part of the reason she has not yet broached her weight loss publicly.

“I’m scared of being judged or yelled at or letting people down,” she said. “Which is ironic, because I think my silence is letting people down more than me talking about it.”

Some of the people who left comments on Davis’ Instagram about her body were kind: “Worried about u … hope you are ok.” Some chastised her: “This sort of rapid and continued weight loss is concerning.” And others were cruel, calling her “sickly skinny.” When Davis started deleting comments, followers decamped to other online forums to speculate further.

“I figure it must be Ozempic like everyone else and she doesn’t want to talk about it, which is a little off brand because she’s so open about everything else,” a user wrote on Reddit.

That commenter told The New York Times that she loved Davis regardless of her size, but still expected answers. “She talks about everything,” she said. “Every pimple she has on her face, every rash she gets on her arm. So why hasn’t she mentioned this?”

“She completely altered her body, and she won’t cop to it,” said another Instagram follower in an interview. She purchased Dôen items because Davis modeled them, including her namesake jeans. “If you’re going to be out there using your body to make a living, and position yourself as a brand, and then you walk away from your brand, I think you can’t expect the community around you to not react,” she said.

‘Life Is Too Hard in This Body’

Right now, body-positive influencers who have decided to be open about losing weight have also had to navigate a community that is often disappointed and angry.

Plus-size influencer Rosey Blair, who is taking Mounjaro, seemed defiant when she posted: “Full transparency: I have zero remorse or shame for being public about my weight loss. Two years ago, I couldn’t wipe my own ass!” Critics called her ableist and self-hating.

“I left the body positive community because I wanted to be defined by my interests outside of my body,” she posted in response.

One creator posted a how-to guide for followers who were wrestling with their reaction to people losing weight: “So, your favorite ‘fat creator’ doesn’t want to be fat anymore? Here are 6 mindset tips to process their journey in a self-loving way for you.” (Her advice in brief: unfollow.)

Longtime curve model Gabriella Lascano filmed a TikTok video last year about her decision to lose weight, explaining that she felt “guilty” for being part of the body-positive movement. She told the Times she hadn’t been honest about “the trials and tribulations of gaining weight and getting older.” People accused her of equating thinness with health and of producing content that could be used to “justify fatphobia.” The outrage was so intense that she removed the video.

“I think it’s strange to be so hurt when someone chooses something for themselves,” Lascano said about the criticism she received.

But influencers’ personal choices affect the community they’ve cultivated, often leaving followers, especially vulnerable young people, feeling disillusioned and adrift. Those who appear to flip-flop can cause “intense feelings of betrayal,” said Sally A. Theran, a clinical psychologist and professor at Wellesley College who has researched parasocial relationships — the one-sided ties people form with media figures and influencers — and disordered eating in adolescence.

“I think if you’re going to put yourself out there, and if you’re going to earn money, then you’re positioning yourself as a leader in this domain, and you should take responsibility for the repercussions,” Theran said.

On a recent episode of the Burnt Toast podcast covering the rise of fat influencers losing weight, Virginia Sole-Smith, a journalist who writes about diet culture and who has contributed to the Times, said that influencers who once promoted fat acceptance but now claim they feel healthier when they are thinner are “throwing everyone else under the bus.”

“You used the hashtags in order to grow your following in order to post your affiliate links, get your sponsor deals, all of that,” Sole-Smith said. “So now what you’re basically telling us is you co-opted all that rhetoric and you don’t believe it at all, and that is pretty gross.”

Her co-host Corinne Fay said she thought it was better for influencers to be upfront if they were using weight-loss drugs instead of vaguely claiming to be “pursuing health.”

“They don’t want to call it a diet, so it’s called a health and fitness journey,” Sole-Smith said. “That’s pretty exasperating.”

Few people, if any, become body positive proponents without struggling with the same societal standards they speak out against. “I’ve seen creators say things like, ‘It’s just too hard, life is too hard, in this body,’” said Katie Sturino, a body acceptance advocate. “It can feel like betrayal, but it’s a symptom of our culture and how in our society it is still the worst thing to be fat. People are still terrified of being in a bigger body.”

With Weight Loss Came Affirmation

Davis acknowledged that with her weight loss came affirmation — more party invitations, more attention from men. “I so badly want to be like, ‘What you look like doesn’t matter,’” she said. “But it sure does change how people treat you.”

When she relapsed, Davis convinced herself she was just trying to eat healthier and be more active. Soon though, she said, she was subsisting on rice cakes and Red Bull. When she ran into friends from the modeling world, she was forced to explain herself. (She pretended she was vegan.) Online, she could evade every question.

“Part of me was embarrassed and felt really guilty,” Davis said. “All I ever wanted to do on the internet was make women feel OK about themselves.”

Davis recently posted an Instagram video of herself posing in a bandanna top and cargo pants for a partnership with Free People. As always, she looks quirkily chic. She also looks thin.

She says she has good days and bad, but that she is trying to be more honest in conversations with friends. She often thinks of how her mother and her grandmother have also struggled with body image their entire lives.

She wants her followers to know that she meant it when she told them to reject fatphobia. “It was always coming from a place that was genuine,” she said.

But given that she is still working on her own issues — and given that she’s no longer plus size — she doesn’t feel it’s her place to advocate body positivity online.

“There was a time when I was in a body where I was experiencing fatphobia,” she said. “Now that I’m not in that body currently, I don’t think my voice is needed.”

When James first noticed that Davis had lost weight, she unfollowed her. “I just didn’t think that was good for me,” she said. But then she noticed her feeds were full of people posting their exercise and diet routines. Davis was just one of many women who were no longer proudly plus size. James re-followed her. And recently, she said, she started working out and shedding pounds herself.

“I guess weight is just as much of a trend as anything else,” James said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2024 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times