Craig Wright did not create Bitcoin, a judge ruled. Here is the inside story of his claims and counter-claims

For years, Australian computer scientist Craig Steven Wright claimed to be Bitcoin founder Satoshi Nakamoto — until a judge found he wasn’t. Here is the inside story of Wright’s claims and counter-claims.

For much of its existence, the cryptocurrency company nChain was governed by a golden rule of office politics: It was not a good idea to challenge Craig Steven Wright, the chief science officer.

At nChain’s London offices, Wright, an Australian computer scientist, was treated as a sort of philosopher king. He wore three-piece suits and drove a Lamborghini. A middle manager would tape Wright’s ramblings about obscure technical matters and then share the recordings with a staff of researchers, who were instructed to turn his musings into patents.

In 2017, Martin Sewell, an employee at nChain, circulated a sceptical memo documenting technical errors in a series of papers that Wright had published about economics and computer science. A manager called Sewell into his office and told him that he had to stop.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The deference to Wright “was just this extraordinary arrangement,” Sewell recalled. “Like he was some sort of god of everything.”

Indeed, Wright’s authority rested on a claim to a kind of divine significance — that he was the mysterious creator of Bitcoin, the original cryptocurrency.

In 2008, a person using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto published a white paper explaining the basics of Bitcoin, a clever idea that eventually became the foundation of a multitrillion-dollar industry. Then, as abruptly as he had emerged, he vanished. Satoshi, who’s known by his first name, controls an estimated 1.1 million bitcoins, a $75 billion stash that has sat untouched for more than a decade.

The mystery of Satoshi’s identity has long obsessed crypto experts, who analyse every record of his communications with the reverence of Talmudic scholars. Various candidates have been proposed as possible Satoshis, only for them to deny any role in Bitcoin’s creation.

Wright, by contrast, has gone to extraordinary lengths to prove that he is Satoshi. He has presented himself as Bitcoin’s inventor in interviews and social media posts, laying out evidence for virtually anyone who would listen. In lawsuits tried in three countries, he has testified that he wrote the original white paper. After a small-time crypto personality challenged his claims in 2019, Wright sued for defamation in England. He followed that up with an aggressive suit against software developers working to improve Bitcoin’s code, accusing them of violating his intellectual property rights.

“A few will be bankrupted, lose their families and collapse,” he declared.

Wright, 53, had a financial interest in squelching their work: He and a gambling tycoon had joined forces to promote an alternative digital currency, Bitcoin Satoshi Vision, that they claimed was a pure, uncorrupted version of Bitcoin, with better practical applications.

This year, Bitcoin’s price surged to an all-time high, renewing optimism that crypto is destined for widespread adoption. But the industry is still tarnished by a procession of recent financial scandals that cost investors billions in savings. The mystery of Satoshi is the last remnant of a more innocent time in its history, when crypto was a renegade, communal system that seemed to have materialised out of thin air.

Wright’s claim to Satoshi-dom wasn’t simply an antagonistic legal strategy: It was a threat to the purity of that founding myth. This year, several of crypto’s most powerful companies mobilised to stop Wright from bringing cases. An influential group led by Coinbase, the largest U.S. exchange, and Block, a company started by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey, took him to trial in the High Court in London.

They were seeking a judicial declaration: We may never know for sure who invented Bitcoin, but it wasn’t Craig Wright.

A Financial Lifeline

Among the mysteries about Satoshi Nakamoto that Wright has tried to explain is the mystery of Satoshi’s name.

Before Bitcoin was invented, Wright worked as an IT security consultant in Australia, but he claims that his interest in creating a new monetary system arose from extensive academic study. At one point, he testified in court, he was enrolled in 19 universities at once, pursuing five doctorates simultaneously. (“I actually wrote three papers last night,” he said at that trial in 2021.) The surname Nakamoto, he claimed, was an homage to a Japanese philosopher whose writing he admired.

Much of what is known about Satoshi Nakamoto comes from hundreds of messages he exchanged with early collaborators, including Gavin Andresen, an American software developer who helped promote Bitcoin in the media. In emails and forum posts, Satoshi wrote about his commitment to privacy and his frustrations with the financial establishment, while revealing little about his background. None of his correspondents ever met him in person.

Then in 2011, with no warning, Satoshi went silent, cutting off communication. “I wish you wouldn’t keep talking about me as a mysterious shadowy figure,” he told Andresen in their final email exchange.

Over the next few years, his identity became a tech-industry obsession. “You can’t help but be pulled into this black hole — the gravity of it is so enormous,” said Andy Greenberg, a longtime tech reporter who has written a book about cryptocurrencies. “Satoshi’s identity is one of the greatest mysteries in the history of technology.”

Hardly anyone had heard of Wright until 2015, when Greenberg co-wrote an article for Wired arguing that Wright was probably Satoshi. The article was based partly on private emails and transcripts supplied by an anonymous leaker: “I did my best to try and hide the fact that I’ve been running Bitcoin since 2009,” Wright said in one transcript. “By the end of this I think half the world is going to bloody know.” (The article included a caveat: “Either Wright invented bitcoin, or he’s a brilliant hoaxer who very badly wants us to believe he did.”)

Wired did not reveal its source, and Wright has denied he was behind the leak. At the time, he was operating on the margins of the crypto industry. He had written some blog posts about Bitcoin, and made it onto a conference panel in Las Vegas.

He was also in serious financial trouble. By early 2015, months before Wired published its article, he was locked in disputes with the Australian Tax Office, which accused him of backdating documents and conducting “sham transactions,” court records show.

Wright needed a lifeline. A former colleague put him in touch with Calvin Ayre, an entrepreneur who had made a fortune in the sports betting industry and wanted to invest in crypto. A Canadian, Ayre was worth at least $1 billion in the early aughts, according to Forbes. In 2012, the U.S. Justice Department charged him with operating an illegal online gambling business. He pleaded guilty to a misdemeanour and avoided prison time.

Before Wired’s article came out, Wright met with Ayre in Vancouver, British Columbia, where they discussed “all things Bitcoin,” according to an account that Ayre gave in 2022. He and a business partner made plans to offer financing to Wright and publicise his Satoshi claim. The eventual deal, outlined in court documents in London, included a loan of 2.5 million Australian dollars to resolve Wright’s tax problems. It also made Wright the chief scientist of a new company, which would have “exclusive rights to Craig’s life story.”

But when the Wired article appeared that December, it drew a sceptical reaction. Wright hadn’t given an interview, which meant some crucial questions remained unanswered. Forbes pointed out that Wright’s resume appeared to exaggerate his credentials. And in any case, there was only one definitive way to prove that he had written the white paper: The genuine Satoshi would have access to cryptographic keys unlocking his Bitcoin stash.

Wright’s sponsors devised a plan to prove that the Satoshi claim was genuine. In 2016, they flew Andresen to London, hoping to secure the endorsement of Satoshi’s old collaborator, who was one of the most trusted figures in the Bitcoin world. In a hotel conference room, Wright gave a demonstration meant to show Andresen that he controlled Satoshi’s private keys.

Andresen, still groggy after his overnight flight from Boston, was impressed. In a blog post titled “Satoshi,” he gave his endorsement, saying Wright’s demonstration proved he had invented Bitcoin.

“I saw the brilliant, opinionated, focused, generous — and privacy-seeking — person that matches the Satoshi I worked with,” Andresen wrote.

Wright’s backers saw an opportunity to profit. He was “the goose that lays the golden egg,” one of his backers told author Andrew O’Hagan. Soon, Wright was supposed to make the cryptographic proof public and end the Satoshi mystery forever. But when the day arrived for the big reveal, Wright didn’t offer any proof. Instead, he published a jargon-heavy blog post about the mechanics of “digital signatures.”

Crypto aficionados dismissed Wright as a charlatan. “I’m starting to doubt myself and imagining clever ways you could have tricked me,” Andresen wrote in an email to him.

Andresen did not respond to requests for an interview. But his correspondence with Wright left him even more confused, he testified at a deposition years later. “I don’t recall thinking anything other than maybe Craig Wright is crazy,” he said.

Why Claim to Be Satoshi?

Hardly anyone knows as much about Craig Wright as Arthur van Pelt. A prolific blogger, van Pelt is the dominant figure in a small but enthusiastic corner of the internet where obsessive historians of the Satoshi saga dissect Wright’s legal campaign.

Van Pelt returns repeatedly to a key psychological question: What would motivate someone to insist that he invented Bitcoin if he hadn’t?

Over the years, van Pelt said in an interview, he has weighed various possible answers, from fame and money to family trauma. In one lawsuit, Wright ordered a medical declaration from a psychologist who had diagnosed him with autism and who described his struggles with a “volatile” and “abusive” father.

“The feeling that Craig Wright has is that he has never been enough,” van Pelt said.

Even after Wright failed to produce the evidence, he retained a band of loyal online followers. He didn’t have access to Satoshi’s private keys, he claimed in court, because he had smashed a hard drive containing them; he described it as an impulsive decision, partly related to his autism.

Ayre stood by him, and in 2018, he and Wright launched Bitcoin Satoshi Vision, which trades at about $70 per coin, a tiny fraction of Bitcoin’s price. Wright oversaw its development from the offices of nChain, a company that Ayre funded as a vehicle for converting his partner’s ideas about crypto into a portfolio of patents.

At nChain, Wright was a difficult boss, prone to shouting, four people who worked with him said. He liked to flaunt his wealth, bragging that he had more money than the entire country of Rwanda. Employees at nChain attended extravagant parties in London: At one memorable event, arranged by Ayre, guests ate sushi off the bodies of naked women, while performers in samurai costumes hovered nearby, two of the people said.

Rejected by much of the crypto industry, Wright pressed his claim to Satoshi-dom in the courts, pursuing litigation that Ayre helped finance. By 2022, his defamation battle reached Norway, where Magnus Granath, a little-known Bitcoin enthusiast who had accused him of fraud on social media, won a judgment against him. That year, Wright also sued the Bitcoin coders, claiming copyright infringement.

“He seems to have enough money and backing from others that he can make good on his threats to ruin people financially by bringing expensive litigation,” Steve Lee, a manager at Block, a company that Dorsey co-founded after Twitter, said in a court filing last year.

Lee was part of a coalition of prominent crypto companies called the Crypto Open Patent Alliance, or COPA, which was founded to stop patent rules from preventing the development of crypto technology. In 2021, Wright’s lawyers asked COPA and its members to remove the Bitcoin white paper from their websites. COPA responded by suing Wright in the High Court in London, seeking a ruling that he did not invent Bitcoin.

As the litigation intensified, Christen Ager-Hanssen, a venture investor, joined nChain and helped oversee Wright’s legal affairs. Ager-Hanssen has a flair for the dramatic: He has acknowledged secretly recording meetings, and likes to compare his work to John Grisham novels. Last fall, he switched sides, saying he didn’t believe Wright’s claims.

On social media, he posted an email that appeared to show that Wright’s relationship with his sponsor was starting to sour. “Every cent spent on your cases is me pissing away my kids’ inheritance,” Ayre wrote. (In a post on the social platform X that was cited in court, Ayre seemed to acknowledge that the email was authentic.)

In an interview, Ager-Hanssen said Wright struck him as clever but delusional, someone who clearly enjoyed the trappings of wealth and status. Still, he said, he found it hard to understand why Wright had spent so many years trying to prove that he invented Bitcoin.

“This is my biggest question,” Ager-Hanssen said. “I believe he thinks he deserves to be Satoshi.”

A Judge Decides

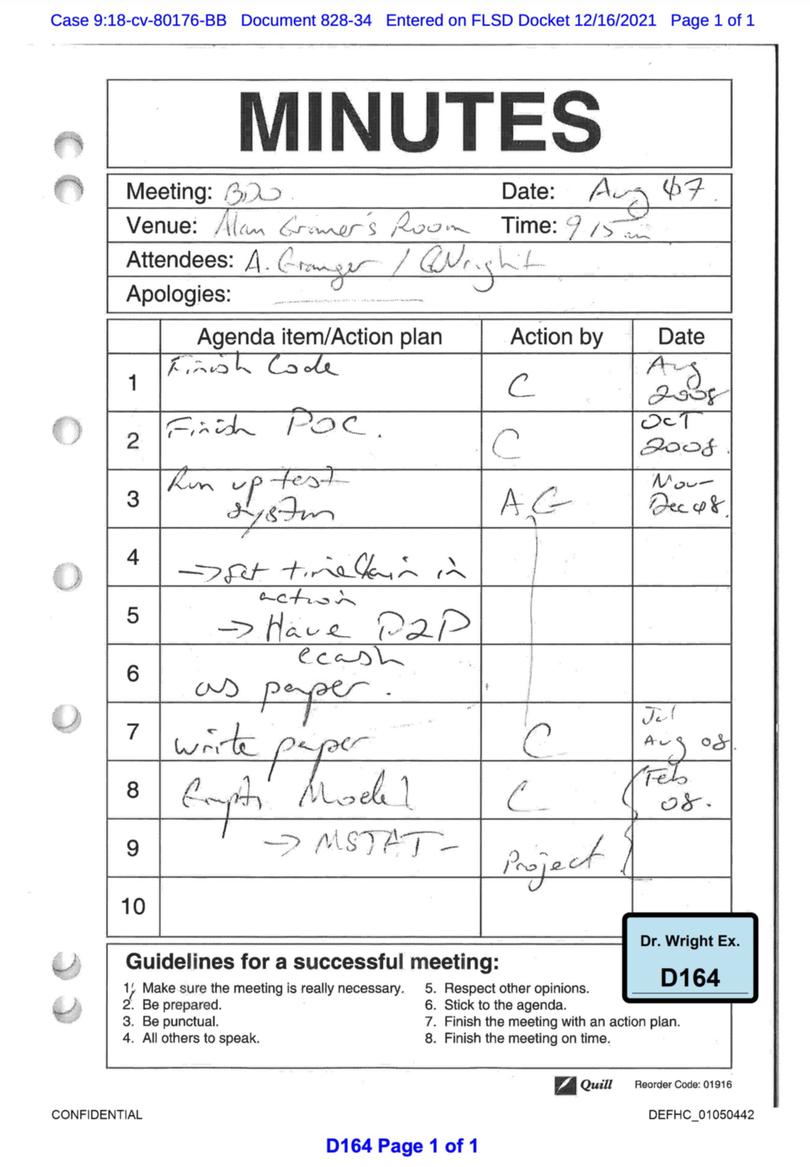

At first glance, the page of notes scrawled on a Quill pad looks like an artifact of potentially historic significance. Dated August 2007, the notes summarize a meeting that Wright held with a colleague in which he discussed a new form of digital money that passes directly from person to person, without an intermediary to oversee the transaction. A list of follow-up steps mentions a “paper,” set for publication in 2008.

The notes were part of a cache of more than 100 “reliance documents” that Wright filed in the High Court as evidence that he invented Bitcoin — the “identity claim,” as the judge described it. Before the trial began in February, a forensic expert hired by COPA submitted to the court an analysis finding that the vast majority of the documents had been doctored.

The notebook entry was one of them. A sworn statement from Hamelin Brands, the parent company of Quill, revealed that the pad didn’t go into circulation until 2012, four years after Bitcoin was invented. Wright took the witness stand in the first week of the trial and insisted that the company was mistaken about the provenance of its own pad.

“Dr. Wright,” COPA’s lawyer responded, “you are making this up as you go along.”

As the trial reached its conclusion in March, a few of Wright’s supporters, mostly investors in Bitcoin Satoshi Vision, gathered in the courtroom to watch his final stand. Ayre was not among them. He had written some supportive messages for Wright on X, but he spent the morning of closing arguments in a pool, drinking beer and posting clips from “The Godfather” on social media.

As Wright’s legal team tried to address the forgery claims, Ayre began texting a New York Times reporter. “Drunk and happy,” he wrote in one of dozens of typo-riddled messages. (The texts came from a number that Ayre had used in the past; it was later disconnected.)

The trial was “old powers wanting to slow innovation,” Ayre wrote. He used a series of vulgar expressions to describe his business rivals and said only a “moron” would disbelieve Wright.

“Craig is Satoshi,” Ayre declared. “He is also 14-year-old kid.”

A few minutes later, the judge overseeing the proceedings, James Mellor, issued a ruling from the bench. “Dr. Wright is not the person who adopted or operated under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto,” he said.

Crypto fans celebrated online, proclaiming the end of a “reign of terror.” Dorsey, the Twitter founder, posted the full text of Mellor’s ruling. In a closing submission, COPA’s lawyers called for the court papers to be forwarded to British prosecutors, who could investigate whether Wright had committed perjury.

Once the most talkative man in the industry, Wright went silent. He did not answer calls or texts requesting an interview, and his name no longer appears on nChain’s website. (The company did not respond to messages seeking comment.)

The week after the ruling, corporate filings in England showed that Wright was transferring assets worth as much as 20 million pounds to an offshore entity. COPA argued that he might be shielding them from seizure by the court, and Mellor ordered his assets frozen. COPA has “a very powerful claim to be awarded a very substantial sum,” the judge said.

This week, Mellor elaborated on his conclusions in a 231-page ruling, finding that Wright had forged numerous documents. “He is not nearly as clever as he thinks he is,” Mellor wrote. Wright has already dropped his defamation claim, as well as one suit he filed against Bitcoin developers. But a message posted to his X account Monday said he planned to appeal the COPA ruling.

The mystery of Bitcoin’s creation seems likely to endure. One morning, in the final stretch of COPA v. Wright, a blond man in a baseball cap shuffled into the gallery, taking a seat among a group of reporters before striking up a conversation. At first, he revealed little about himself, other than his devotion to personal security. A back brace he had started wearing after a motorcycle accident served as a convenient “stab vest,” he explained — no knife could penetrate it. For supplemental protection, he had reinforced the lining of his hat with plastic, which he planned to upgrade to Kevlar.

But why had he shown up to Wright’s trial? He leaned in to whisper a secret: He was the real Satoshi Nakamoto.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Originally published on The New York Times