Ryan Peake: The former Rebels bikie who won the New Zealand Open and will now play in the British Open

Ryan Peake wanted to turn his life around by choosing golf over crime, now he is the NZ Open champion and has booked himself a spot at one of the most prestigious tournaments on the planet. This is his story.

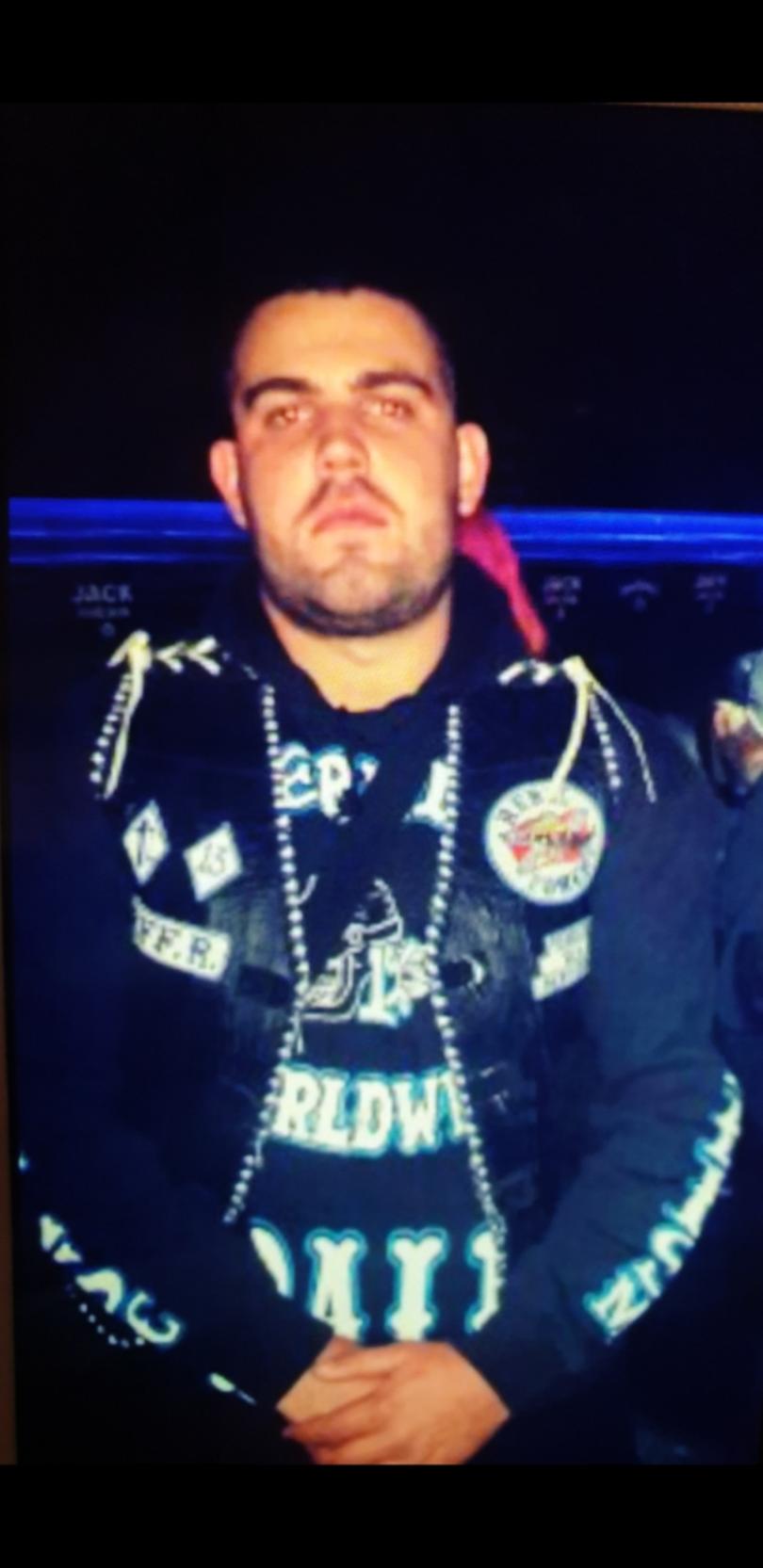

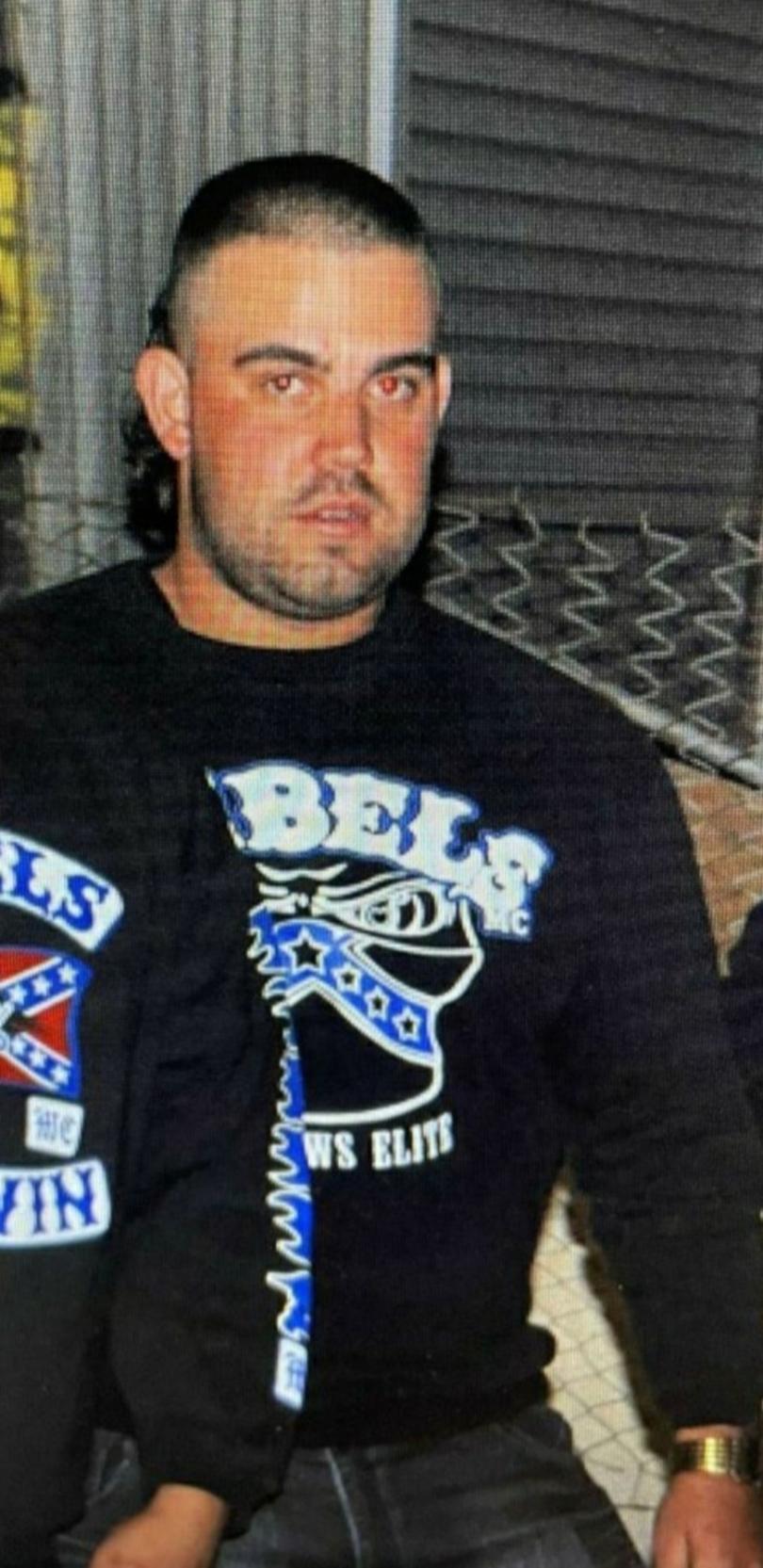

In 2022 Ryan Peake detailed his struggles as a young man which lead him into the Rebels bikie gang, how he got out and how he ended up the fairway.

His win at the New Zealand Open on Sunday not only earned him $300,000 but secured him a a spot in the British Open this year. The West Australian’s chief reporter Ben Harvey got a fascinating insight into his back story. Read it here:

“Child prodigy golfer becomes Rebels bikie and goes to jail for five years.” That’s not a bad news story.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Add “at lowest point receives letter from legendary golf coach who lures him back from underworld” and you have an engrossing magazine feature.

Finish with “hands in bikie colours, starts gruelling training regime and wins club competition while on day-release from jail” and you have the ingredients for a cracking book.

If Ryan Peake ever wins a major, his story will surely become a Hollywood film.

He isn’t speaking about his life as a warning to other young men to stay away from bikies.

He probably doesn’t need to because going to jail for a formative part of his life is rude testament to the perils of going down the outlaw road.

Nor is he speaking because he feels he has finished the job of turning his life around. Read on and you will learn that’s still a work in progress.

He’s talking by way of apology to the friends and family he let down and to explain why he made some apocalyptically stupid decisions.

The mishmash of sport, violence and prison redemption that has shaped this 29-year-old demonstrates that, sandwiched between the navy blue uniforms of the gang crime squad and the blazing red, white and blue patch of the Rebels Outlaw Motorcycle Club, there is a lot of grey.

And it shows that the Road to Damascus can start in odd places; in Peake’s case, the first tee of the Lakelands Country Club in Perth’s northern suburb of Gnangara.

NATURAL TALENT

Hitting a long, straight tee shot in golf requires a lot of actions to come together very quickly.

A good player is able to combine torque, centripetal force and the double pendulum effect (the pivoting of first, shoulders, and then wrists) inside 1.5 seconds.

The club will be moving at between 215km/h and 250km/h when it collides with the ball, which will launch at close to 300km/h and come to rest on the fairway up to a third of a kilometre away.

I don’t want it to come across as ‘poor me’ because I loved it back then. I lived and breathed golf but that meant I was always around older people. It made me different.

Five years after quitting the Rebels, Peake no longer looks like a bikie but at 185cm and 105kg he’s still built like one. He doesn’t hit a golf ball; he punishes it.

“I wasn’t always a golfer,” he says. “I played footy and cricket. My grandfather, my father and one of my cousins would play golf and I would go out with them.”

His father became a greenkeeper after ruining his body as a brickie and had seen plenty of good golfers swing a club. He knew when he watched his son effortlessly shift his weight through the ball that this 10-year-old had talent.

“I was going to East Wanneroo Primary and I was playing at the club in Lakelands.

“A few people saw I had potential and I started taking lessons.

“It is a pretty lonely thing for a kid to do to be honest. My friends would be out on their bikes and I would be practising golf out there by myself.

“I don’t want it to come across as ‘poor me’ because I loved it back then. I lived and breathed golf but that meant I was always around older people. It made me different.”

The law of the schoolyard dictates that difference is punished and Peake was bullied relentlessly.

“There was one bigger kid who was really making my life hell. It got to the point where my dad had to come to the school and make sure I was OK and I’d be walked home.

“It got very bad. And then one day I bashed him.”

It’s a common tale told by men who join bikie gangs. Stereotypical? Yes. But also an undeniable theme.

Psychologists will get giddy at the prospect of drawing a line between that moment — understanding the power of a show of strength — and the decision to become a one percenter. But Peake won’t have a bar of the psychobabble.

“I wasn’t that popular and to be honest I was probably a bit of a dickhead which meant I was a loner and the guys in the bikie club accepted me for who I was.

“It’s pretty much that simple.”

SPORTING HIGHS AND LOWS

Peake’s bedroom began filling with trophies as he played as an amateur.

In 2009 the then 16-year-old came second at both the South Australian Junior Masters and Tasmania’s Tamar Valley Junior Cup. He won the Tasmanian Junior Open Championship and was that year’s Srixon Junior Champion and West Australian junior champion.

A year later he partnered with Cam Smith to win the Trans-Tasman series in New Zealand.

“He would stay at my house whenever there were events in Perth because he lived in Queensland.

“From what you see on TV now he is exactly how he was when we grew up. He hasn’t changed except he now has a mullet and $200 million.”

The year 2010 saw Peake take out the Mastercard Amateur Masters and place second in Malaysia’s Saujana Amateur Championship.

“In 2010 I played the Australian Open and that was an unreal week of my life. I was 17 and that field had guys like Adam Scott, Greg Norman, John Daly and Fred Couples.”

A year later he came 10th in the WA Open.

It was an impressive streak but Peake felt he was underachieving.

“I needed a circuit-breaker and I was about 19 when I decided to turn pro. I wanted to see if my attitude changed if I was playing for money.”

It didn’t. The 2012 WA Open at Royal Perth was disastrous.

I didn’t know what I was going to do. I felt I had let everyone down.

“It was my first pro event and I was playing with guys like Oliver Goss, who won it, Brett Rumford, Jason Scrivener, Ryan Fox and Kim Felton. I finished 36th and I didn’t enjoy it at all. I didn’t really want to be out there even though I acted like I did.”

Then came tour school at The Peninsula golf club in Victoria — a week-long golfing Hunger Games where 200 players hit three rounds of stroke with the top 50 or so getting through to the final stage and the chance at one of 30-odd professional cards.

“I missed the cut and that was without doubt the loneliest week of my life. When I got back to WA I went to Royal Perth to practise. I sat in the car for half an hour because I didn’t want to get out.

“Eventually I popped the boot. My clubs weren’t there and I realised I had no idea where they were. That’s when I knew it was over.”

It was a quick descent. He started drinking hard and his already beefy 95kg frame ballooned to 130kg.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do. I felt I had let everyone down.”

A sliding doors moment loomed.

REBELS YELL

“I had known a couple of Rebels bikies even when I was playing golf. Not close, they were just friends of friends. I knocked into them a few times at parties and they’d occasionally ask whether I wanted to come back to the clubhouse in Ocean Keys for a drink.”

“I had been saying no but one Friday I decided to go and have a look. It was totally different to what I expected. I didn’t know much about bikie clubs apart from what I had read or seen on TV so I thought it would be a dingy place.

“It wasn’t at all. The first couple times I went I spent the whole time just talking to one of the guys I knew because I was trying to keep my head down. Then one of them said ‘you know this c...’s a golfer, right?’.”

Peake froze, worried this news would be met with the same derision it had in the schoolyard.

I knew straight away they wouldn’t see what I saw in the club. I felt I had disappointed them. They had sacrificed so much for my golf and I felt like I had let them down.

“Once they understood I was actually really good they were stoked they knew someone who did something like that.”

He was spending most Friday nights at the clubhouse and had been on club runs on the back of someone else’s Harley.

“I kept asking to join because I thought that’s what I should do as a good mate. They didn’t want me joining though. They said I should just enjoy being part of the furniture.

“The president at the time eventually said to me ‘you’re not going to stop asking are you?’”

The public perception of life as a bikie nominee is one of ritualistic abuse in which you are forced to commit crimes to prove your worth.

Appalling hazing ceremonies are common at most clubs and Peake’s experience — he smiles at the suggestion he was forced into servitude as a drug mule — should be viewed as the anomaly it is.

“I understand that in some people’s opinions that stuff happens at bikie clubs; I’m just saying it wasn’t my experience. You serve drinks and you keep the club clean and help take out the bins. If we had a BBQ then I’d make sure the BBQ was ready to go and the gas bottles were full.

“It’s no different to being a guest in someone’s house. If I was at your house and the bin was full then of course I’m going to help take it out. Some people reckon it’s like you’re a slave but I saw it as just not living like a slob.”

PATCHED UP

“I was almost 21 and I was asked into the members’ room.

“If you’re a nom you’re always hoping when you are called in it’s going to be the moment you get your colours but it usually isn’t.

“I walked in and the chapter presidents were all there. They shook my hand and everyone gave me a hug and they handed me the patch. I had it sewn on the vest the next day.”

Peake remembers his first run on his Harley — a Street Bob — as a patched member.

“There is nothing else in the world like that feeling. I can’t describe how much pride I felt to be wearing the colours and knowing I had earned the right to be there.”

It was a secret pleasure.

“My parents knew I was hanging out at the club but they didn’t know I was a nom and had no idea that I’d become a member. I’d push my bike down the road and put my vest on later out of respect for Mum and Dad.”

He was outed in an embarrassingly un-underworld way.

“My mum used to do my washing and one day I saw some Rebels gear drying on the line,” Peake says with a sheepish grin.

“My father asked me about it and he said ‘I don’t care what your answer is, just don’t lie to me. Are you in the club?’ I said yes. He just walked back inside without saying anything.

“I knew straight away they wouldn’t see what I saw in the club. I felt I had disappointed them. They had sacrificed so much for my golf and I felt like I had let them down.”

He loved being around the club and spent time there when he wasn’t working as a greenkeeper at Lakelands. He came to know Nick Martin and Martin’s then sergeant-at-arms, Karl Labrook.

“I didn’t have a heap to do with Nick personally other than when we all got together for parties or rides. I was a lot closer with Karl and still am.”

Even the Rebels’ war with the Rock Machine gang, which was led by the fierce-looking Brent “BJ” Reker until he defected to the Finks, didn’t put him off.

“I was obviously aware of my surroundings insofar as if a group of guys come storming in my direction I’d punt that they were probably there to see me.

“I’m not speaking about this to be an apologist for bikies. I’m just going to say this. If you put a taskforce on your local footy club you’d find a lot of them doing the wrong thing.

“Not everyone in the club is going to be a straight shooter but it’s not like you see on TV or in the movies. If someone breaks the law it’s an individual act. Yes, there’s no doubt that quite a few bikies are convicted criminals.”

Peake knows that for a fact because by the time he joined the Rebels, the man who had once played alongside Greg Norman was a criminal himself.

A LIFE OF CRIME

The three parts of Peake’s rap sheet were created in a cauldron of stupidity and bad luck.

“I was at the casino when I was 18 and I got into an argument with a guy over a girl. He says ‘you don’t know who you’re f...ing with’.”

Peake pushed him into a table, unaware the guy he was f...ing with was a cop. He was charged while assaulting a public officer but escaped with a spent conviction.

A couple of years later he was walking with some mates across the Horseshoe Bridge in the city when an argument broke out with a passing group.

“One of them told me to keep walking and I said to him ‘yeah whatever’ and I pushed him in the face.

I was standing on the driveway when the garage door started going up. This guy runs out and he’s lifted his shirt and I’ve seen this brown thing. I didn’t know what it was but I dropped him.

“He wasn’t hurt at all but he spun around and he started walking faster to get his balance back. He was kind of lurching forward with his head down and his head went straight into a metal box that was on the footpath.

“I was a bit nervous because GBH is serious but I still didn’t think it was going to be an issue because the CCTV showed something happening that I couldn’t have predicted. That metal box was four metres away from where I pushed him.”

His fate was sealed nine months later, not in court, but in the driveway of a house in Clarkson.

“This is the bit where I completely f...ed up,” he says.

The Rebels believed a local man had threatened to shoot one of them and Peake was among of six club members who paid him a visit.

“I was standing on the driveway when the garage door started going up. This guy runs out and he’s lifted his shirt and I’ve seen this brown thing. I didn’t know what it was but I dropped him.”

The ‘brown thing’ was a sawn-off shotgun. The Rebels beat him with an aluminium baseball bat, fracturing his skull and breaking his arms and legs.

Peake’s life changed forever on November 11, 2014.

“I was at the golf course and I had just come in for smoko. The guys I worked with said they could see a cop car coming down and they made a joke about the police being there for me.

“When I saw it was gang crime I thought ‘well, they’re not here for anyone else’.

“I was worried about mum so the first thing I said to them was ‘please don’t tell me you’ve kicked my door down’. They said they hadn’t and explained that we’d go back home and there’d be a search.

“I was taken to the Northbridge lock-up and there’s a cop there I used to play golf with. He shook his head and said ‘what the f..k are you doing?’ I didn’t know what to say.”

He went straight to Hakea Prison.

His latest crime was committed as a patched bikie who was on bail for another assault and the experienced inmates told Peake he was in line for a decent stint in jail.

Four years after being crowned WA Golfer of the Year, Ryan Peake started a five-year sentence in jail. He was 21.

PRISON TIME

“For the whole first year at Hakea I didn’t see my mum. She wanted to come but I didn’t want her to see me like that.

“I was a mess but I started running. At first I couldn’t do more than a quarter of a lap of the oval before I had to start walking.”

He spent the bulk of his sentence in a self-care unit at Acacia Prison and counted some infamous men as housemates.

Aaron Carlino killed underworld heavy Stephen Cookson before spending six hours using an angle grinder to dismember his victim’s body.

Cookson’s head was discovered at Rottnest Island.

Brothers Ambrose and Xavier Clarke murdered family man Peter Davis, stuffing his body in the boot of a car found in Rivervale.

Douglas Crabbe killed five people when he ploughed his Mack truck through the Inland Hotel in Uluru in 1983 after being thrown out.

“I was going nowhere. I didn’t have a clue what I’d do when I go out and was pretty much convinced I’d never do anything good in my life.”

A STRANGE NOTE

It was less a letter and more a slip of paper. On it were four words: Richie Smith, Sports Coach.

Peake knew the name and recognised the mobile phone number.

Smith was a legendary golf coach who had helped Hannah Green to world number one and Minjee Lee to number three.

“I rang Ritchie and he said to me that he’d heard what had happened and asked me what I was going to do. I said I was thinking about an electrical apprenticeship.

“He went quiet. Then he said ‘what about golf?’”.

“I had two years left on my sentence and I decided I was going to do it. When I watched tournaments on TV I started feeling a real competitive streak.

“I knew I could never give 100 per cent to the club if I was going to play golf again. How could I say ‘nah, I can’t go on that club run because I’ve got a tournament on’?

“How does a bikie go to Thailand for a tournament? What’s the AFP going to say about that?

“I knew I had to quit. I was being housed with other guys in the club and I ran the idea past them. As soon as I told them they said I should go for it. That’s why I will never turn my back on these guys. They genuinely wanted what was best for me.

“I got my parents to box up my Rebels stuff. A couple of guys came to mum and dad’s house to pick up my vest and everything else. They had a beer with my dad.

“They also collected the bike. I knew when I bought it that it was the property of the club. They didn’t push it but I wanted them to have it.”

Like his experience as a nominee, Peake’s exit was also an anomaly. He was lucky; many men who want to leave a bikie gang end up in hospital or worse.

Peake smiles at the absurdity of what happened next.

“So I’m talking to my parole people and I’m saying that you need to send me to Wooroloo because I need to be in minimum security so I can train because I’m not going to be a bikie anymore and I’m going to become a professional golfer.

“I was worried they’d put me in a mental care unit.

“I’d had a shoulder operation in jail and I was telling everyone that my golfing coach had told me I needed a really good physio to get a full range of motion and that he knew what he was talking about because he was coaching the women’s world number one.

“It must have sounded ridiculous.”

The last year of his sentence was served at Wooroloo. He was allowed home visits, starting with 12 hours of freedom once a fortnight.

Peake remembers the first time he stood on the driving range while on day release. He hadn’t held a club for seven years.

If his life is turned into a film this would be the moment he sends the Titleist soaring in a symbolic nod to his own freedom.

“My swing felt terrible and it came off the club like a brick,” he laughs.

The cobwebs were brushed away fast and on his third home visit Peake won the Lakelands club competition.

“I was standing there making my speech and I ended it by saying ‘I hope you enjoy your night but I’m back off to jail’.”

He was released in May 2019.

HAVING A CRACK

As with his swing, Peake’s life is now all about timing.

“You’re one shot away from being the best in world and one shot away from quitting and because of that you need to keep playing.

“You need to spend time on the course so that the odds are better of you being in the right place at the right time when it does come together. The chances of it happening even for the very, very best are pretty slim so a lot of it comes down to time. And time means money. I need money to be able to spend the time on the course and I need money to be able to travel so I can play in comps.”

He has taken a fly-in, fly-out job which he hopes will allow him to spend time on the course on his off-swing. He is convinced he has what it takes to make it.

I am watching the guys playing at the moment and I know I can beat them if I just had more time with the clubs. I’m not going out that easy. This time it’s for me.

Ritchie Smith is circumspect.

“This guy was very good. When I say ‘very good’ I mean Cameron Smith-level good,” Mr Smith explains.

“He has the courage to have a crack and that counts for a lot but he is now eight years behind where he should be and the people he is competing against are practising 50 hours a week. Try doing that when you are doing a 40-hour week to pay the bills.

“Yes, the chances are low but it is absolutely worth the risk.”

Peake knows that if he publicly condemned the Rebels and blamed them for his lot in life he would have a better chance of picking up the sponsorship that would give him the financial breathing space to practise.

He refuses to. One of the first things he said during this interview was: “Don’t expect me to bag out bikies.”

Peake isn’t waiting for a Road to Damascus moment of conversion because he doesn’t feel he needs one.

He is, finally, comfortable in his own skin.

“I am watching the guys playing at the moment and I know I can beat them if I just had more time with the clubs. I’m not going out that easy. This time it’s for me.”

Originally published as Ryan Peake: How a pro-golfer became a Rebels bikie and is now back on course after jail