Rodney Alcala: How serial killer won US dating show as seen in Netflix’s Woman of the Hour

For British audiences, it’s a much-loved format. A member of the public chooses who to date from a selection of three suitors, based solely on their answers to questions — the twist being that the candidates are hidden behind a screen so the person on the other side can’t see what they look like.

But while Blind Date, hosted by Cilla Black, made gripping viewing for millions in the 1980s and 1990s, as far as anyone knows, it never featured a serial killer.

The same can’t be said for the US forerunner of the show.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Rodney Alcala seemed like the perfect contestant when he appeared on The Dating Game in 1978, but in reality, the self-styled playboy was in the midst of a murder spree and was a predator so ruthless that one of Los Angeles’s top detectives has called him the “most evil, cunning and remorseless killer” he had ever come across.

Tall, handsome and charming, Alcala was “Bachelor Number One”. He flirted with contestant Cheryl Bradshaw — an aspiring actress who had to choose from three suitors — saying suggestively that his “best time is at night”, words that now come with chilling connotations.

When the 35-year-old was declared the winner, he was introduced to his date as a “successful photographer” who enjoyed skydiving and motorcycling in his spare time.

What nobody realised, because producers who selected him for the show had failed to undertake background checks, was that he was none of these things. In reality, he was a convicted rapist who had only been released from prison the year before.

Worse still, by 1978 Alcala — whose appearance on The Dating Game can still be seen in old clips on YouTube — had already killed at least two women in Los Angeles and two in New York. Although his true death toll remains unknown, the authorities estimate he could have killed up to 130 people.

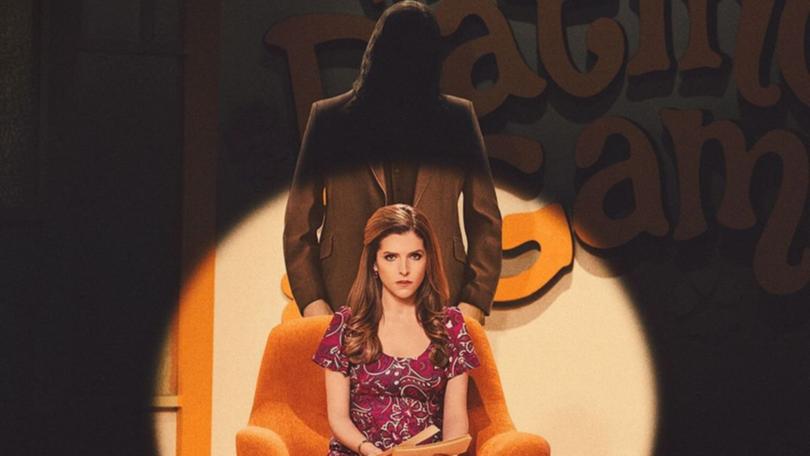

The horrific story of how a serial killer managed to pose as an eligible bachelor on prime-time TV and get away with assaulting and killing young girls and women for years is the subject of a gripping new Netflix film, Woman Of The Hour, directed by and starring Anna Kendrick.

The Mail has spoken exclusively to people involved in the case, including two survivors who gave astonishing testimony about their terrifying experiences. One, left fighting for her life aged eight after she was raped and beaten by Alcala, says: “The thing that angers me is that the court system kept giving him a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

Another, who was 16 when she was subjected to a brutal assault that was dismissed by police, recalled: “He was like a raging, ripping animal. I thought I was going to die.”

Certainly, those who encountered Alcala on The Dating Game said he made an alarming first impression.

“He was creepy, really creepy, and I instantly disliked him because he had this attitude of being superior to us,” actor and director Jed Mills told the Mail. Now 83, he appeared on screen next to Alcala as ”Bachelor Number Two”.

“He was behaving strangely, even in the green room before we went on air. I was talking to the third contestant and Alcala jumped into the conversation and said, ‘I always get my girl.’ It wasn’t until later that we found out that the way he got girls was by killing them.”

Given his history, it is staggering that Alcala was able to make it onto television. Born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1943, he had joined the US army at 17 but was given an honourable discharge after being diagnosed with an antisocial personality disorder. He then went to the University of California, Los Angeles, graduating in fine arts in 1968.

In the same year, then aged 25, he abducted the eight-year-old girl on Los Angeles’s famous Sunset Strip as she walked to school. She only survived because a motorist became suspicious when he saw the girl get into a car and followed it before calling the police.

Officers arrived at Alcala’s apartment and he answered the door naked. He then said he would get dressed but fled out the back. Police found his victim, who had been beaten with a steel bar, in a pool of blood and fighting for her life.

Now on the FBI’s Most Wanted list, Alcala next turned up in New York, reinventing himself as a man called John Berger. He became a student at New York University film school and set himself up as a photographer as a way of meeting young women.

He even got a job as a counsellor at a New Hampshire arts centre. But after two of his young female students spotted his face on an FBI poster in 1971 at a post office, he was finally arrested. “He was as cool as a cucumber and the only thing he said was: ‘It’s not my fault, he did it,’” recalls Steve Hodel, a retired detective with the Los Angeles Police Department, who was instructed to bring Alcala back to LA to stand trial.

His cryptic comment, says Hodel, was meant to put the blame on his evil alter ego: “He was playing games with us, trying out a Jekyll and Hyde scenario. He was a very smart guy, very cunning. I’ve got more than 300 murder investigations under my belt, and I rank him as the worst in my experience.

“He was the epitome of a wolf in sheep’s clothing. He had no empathy, high intelligence and a strong ego, and all of those came together in a perfect storm to make him the monster that he was.”

The parents of the eight-year-old girl, who had been in a coma for a month after the attack, refused to put her through the ordeal of giving evidence, and police were forced to make a plea deal, allowing Alcala to testify to a lesser charge of child molestation.

Because of rules at the time, Alcala was sentenced to “one to 99 years”, says Hodel.

“I figured he would do at least 20 years — the little girl almost died — but he fooled the prison psychologist into thinking he was reformed and he got early release. The system broke down.”

After only 34 months in custody, Alcala was paroled in 1974 and back out on the streets.

Within weeks he’d approached a 13-year-old schoolgirl at a bus stop in Huntington Beach, California, and persuaded her to go to a beach, where he planned to attack her. However, a park ranger spotted them, and Alcala was arrested.

Returned to prison, he was again released on parole in 1977, and just a year later, he was charming Cheryl Bradshaw on The Dating Game.

She sensed something was very wrong with Alcala and refused to go ahead with their date.

“She said: ‘I can’t go out with this guy,’” The Dating Game’s contestant co-ordinator Ellen Metzger recalled.

“She said she didn’t feel comfortable with him and that she felt weird vibes coming off him. She asked if it was ok not to go on the date and I said: ‘Of course, you shouldn’t.’”

A teenager he picked up in February 1979 survived her attack, leading to his arrest. But after his mother paid to bail him out, he went on to kill Jill Parenteau on June 14 1979. Twelve-year-old Robin Samsoe was murdered six days later after disappearing while riding her bike to a ballet lesson.

Alcala was arrested on suspicion of Robin’s death. The investigation uncovered earrings identified as belonging to the dead schoolgirl in a locker he had rented in Seattle, along with other jewellery, trophies of further crimes, and more than 1,000 sexually explicit photos of women and girls.

In 1980 Alcala was convicted and sentenced to death for Robin’s murder, but twice his convictions were overturned on technicalities, though he remained in custody.

His third prosecution took place in 2010, for Robin’s murder as well as the killings of four other women: Jill Barcomb, 18, murdered in 1977; Georgia Wixted, 27, murdered in 1977; Charlotte Lamb, 31, murdered in 1978 and Jill Parenteau, 21, murdered in 1979. He was found guilty of all of them and sentenced to death.

Alcala’s first known (at that time) victim, attacked when she was eight and by now an adult, gave evidence. Tali Shapiro, now 65, spoke exclusively to the Mail about that experience.

“I chose to testify against him because I had the right to come forward and say my piece,” she says, explaining that she had no memory of the attack itself as she had been beaten unconscious.

“He (Alcala) was defending himself and he apologised to me. I didn’t listen to him or look at him. I didn’t give him any energy —whatsoever. He wasn’t getting rewarded by me in any way.”

Tali, who lives in California, adds: “The thing that angers me is that the court system kept giving him a get-out-of-jail-free card. The US army wanted rid of him. And who lets a man like that on a dating show?”

Another of Alcala’s victims, who was attacked shortly before Tali, came forward a few years ago and she and Tali have become friends.

Morgan Rowan, now aged 72, was 16 when Alcala assaulted her in 1968. She and her friends had been on a night out at a nightclub for teenagers on Sunset Strip when Alcala gave the group a lift. They ended up at the killer’s apartment, and as a party got underway, he grabbed her and pulled her into a bedroom, barricading the door with a metal bar.

“I remember saying: ‘Why are you doing this?’ and he came across the room very quickly and backed me up against the wall,” she told the Mail.

“I could see the transformation in his face. His face swelled up and his skin was grey and then crimson. His eyes were evil.”

Alcala punched Morgan in the face, tied her hands and started ripping off her clothes as music from the party drowned out the teenager’s cries for help. “I fought him the whole time, but he rammed the belt down my throat so I could hardly breathe and punched me so hard he broke my ribs.”

By this time, her friends had noticed she was missing and started banging on the door.

“He got really angry at that and raped me and started to strangle me, and (then) I heard the sound of breaking glass.”

One of her friends, unable to get through the barricaded door, had gone outside and smashed the bedroom window.

Wearing only a blouse and with her hands still tied behind her back, Morgan and her terrified friends rushed for the door and hid behind a rubbish bin outside the building.

The traumatised youngsters then went to a friend’s house and called the emergency services.

More than 50 years later, Morgan’s voice still falters when she tells me that the police officer who interviewed her didn’t seem to take the attack seriously, pointing out that she and her friends had willingly gone to Alcala’s house.

“The officer did not even file a report. It was a different era,” she says.

She never told her parents and Alcala was never prosecuted.

She was horrified when she learned from newspaper reports that Alcala had attacked and nearly killed an eight-year-old girl shortly afterwards.

Morgan said she nearly “drowned in guilt” and kept her secret for many years. But after she discovered Tali’s identity in 2010, she made contact with her.

“Tali told me I had nothing to be sorry about and that the only person to blame was Alcala,” says Morgan quietly. The two women have since become friends, and Morgan wrote a book about their experiences called Stolen From Sunset.

Further prosecutions followed and in 2013 the sadistic killer pleaded guilty to the 1971 murder of Cornelia Crilley, a 23-year-old TWA flight attendant who was killed in her apartment in New York. He also admitted the murder of 23-year-old nightclub heiress Ellen Hover.

In 2016, thanks to advances in forensic science prosecutors in Wyoming charged Alcala with the murder of 28-year-old Christine Thornton, who disappeared in 1977 and whose body was found in 1982. In July 2021, still awaiting execution on Death Row, Alcala died from natural causes aged 77.

Needless to say, his death was not mourned by anyone.

“I was going to open a bottle of champagne when he died, but instead, I just cried and cried,” says Morgan.

“He left behind so many unanswered questions and so much pain.”

Another unanswered question is what happened to Cheryl Bradshaw. After her appearance on The Dating Game, she went on to marry and raise a family and dropped out of the spotlight.

Still, as Tali says: “Bad things happen to good people . . . and I’m very glad that girl on The Dating Game was smart enough to say no.”

Originally published on Daily Mail