New DNA study finds Hitler had Kallmann syndrome, a disorder linked to micropenis and delayed puberty

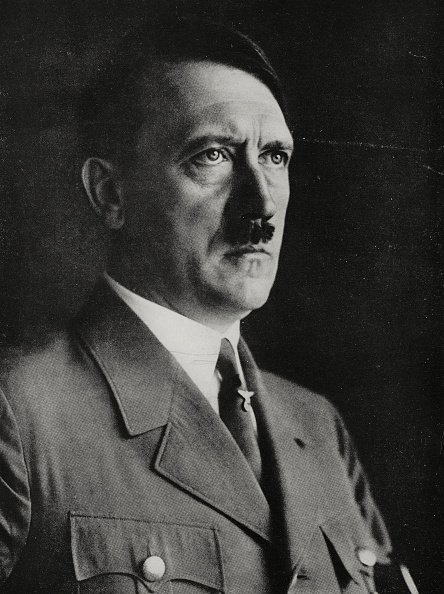

Researchers say Adolf Hitler’s genome reveals a disorder that may explain his sexual difficulties and single-minded political obsession.

Eighty years after victorious Allied troops picked their way through the suffocating darkness of Adolf Hitler’s underground bunker, a scrap of blood-soaked upholstery has rewritten what we know about the man who reshaped world history through violence, paranoia and brutality.

What a soldier treated as a grim souvenir in 1945 has now become the unlikely foundation for an unprecedented scientific breakthrough: the first sequencing of Hitler’s DNA.

The unlikely custodian of that relic was Colonel Roswell P Rosengren, a US Army press officer assigned to General Eisenhower. While sifting through the Fuhrerbunker in the days after Germany’s surrender, Colonel Rosengren spotted the battered sofa where Hitler ended his life.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.He sliced away a square of fabric still marked with the dictator’s blood and quietly stowed it away, taking it home across the Atlantic. The cloth would sit in obscurity for decades before its significance became clear.

That fragment has now fuelled a landmark project detailed in a new Channel 4 documentary, Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator, which airs Saturday.

The findings push into territory previously shaped by rumour, speculation and psychoanalysis, revealing what the filmmakers describe as an unprecedented look at the “biological design” of the architect of the nazi regime.

For Professor Turi King, the globally recognised geneticist who led the research team, the results are as provocative as they are unsettling. They also pierce the monstrous mythology Hitler constructed around racial purity and biological destiny.

“If he was to look at his own genetic results, he would have almost certainly have sent himself to the gas chambers,” Ms King said.

Ms King, who previously identified the remains of Richard III, admitted she grappled with whether such a project should even be undertaken.

“I agonised over it,” she said.

“But it will be done at some point and we wanted to make sure it’s done in an extremely measured and rigorous fashion. Also, to not do it puts him on some sort of pedestal.”

She stressed the limitations of the work and pushed back against any narrative suggesting that genetics can soften history’s judgment.

“The genetics can in no way excuse what he did. He could have had the most boring genome on the planet,” Ms King said.

“But he didn’t.”

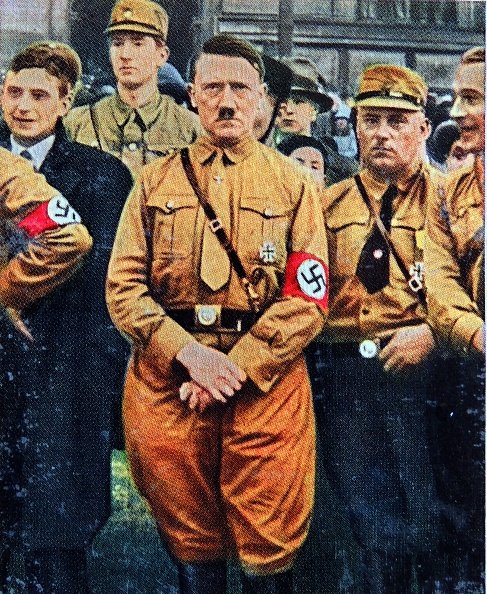

The most definitive conclusion reached by the team is that Hitler had Kallmann syndrome, a genetic disorder that disrupts puberty and the development of sexual organs. Crude wartime songs about the dictator’s anatomy may have been born in mockery, but according to the researchers, they were closer to the truth than anyone knew.

The implications, while speculative, add a new dimension to how historians view Hitler’s personal life and political fixation. Alex J Kay, historian at the University of Potsdam and a co-investigator for the documentary, argues the condition may have shaped Hitler’s near-total devotion to ideology over intimacy.

“This would help to explain Hitler’s highly unusual and almost complete devotion to politics,” Mr Kay said.

“Other senior nazis had wives, children, even extramarital affairs. Hitler is the one person among the whole nazi leadership who doesn’t. Therefore, I think that only under Hitler could the nazi movement have come to power.”

Hitler’s ancestry myths fizzle under the microscope: rumours that he was secretly descended from a Jewish grandfather are not supported by the genes. More complicated is the suggestion that Hitler had a high likelihood of several neurodiverse or mental health conditions.

Using thousands of samples to produce polygenic scores, not diagnoses, the team determined he ranked in the top percentile for traits linked to autism, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

The documentary treats this territory cautiously.

According to The Times, Professor Sir Simon Baron-Cohen of Cambridge University, who appears in the film, warned that misinterpretation risks harming people who share these traits in everyday life.

“Associating Hitler’s extreme cruelty with people with these diagnoses risks stigmatising them, especially when the vast majority of people with these diagnoses are neither violent nor cruel, and many are the opposite,” he said.

While “full of admiration” for the research, he insisted it must not recast Hitler’s crimes as the product of neurobiology.

Authenticating the genetic material was its own scientific saga.

Colonel Rosengren’s swatch surfaced in the Gettysburg Museum of History, allowing researchers to extract samples in 2019.

Verification came through earlier work by Belgian journalist Jean-Paul Mulders, who had located a Hitler relative carrying the same paternal lineage. When Colonel Rosengren’s blood sample was compared, the Y-chromosome match was exact, rare, uncontaminated and consistent with an 80-year-old sample.

For Ms King, the project’s legacy is not the shock value but the reminder that biology is never destiny. “The biggest thing I want to have come out of this is the complexity of genetics and the complexity of conditions,” she said.

“People often view DNA as deterministic, which it is not. DNA is always just a part of the puzzle about who somebody is.

“You cannot see evil in a genome.’’