The New York Times: Israeli hostage Amit Soussana says she was sexually assaulted and tortured in Gaza

Amit Soussana is the first Israeli to speak publicly about being sexually assaulted during captivity after the Hamas-led raid on southern Israel. Warning: Distressing content.

WARNING: DISTRESSING CONTENT.

Amit Soussana, an Israeli lawyer, was abducted from her home Oct. 7, beaten and dragged into the Gaza Strip by at least 10 men, some armed. Several days into her captivity, she said, her guard began asking about her sex life.

Soussana said she was held alone in a child’s bedroom, chained by her left ankle. Sometimes, the guard would enter, sit beside her on the bed, lift her shirt and touch her, she said.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.He also repeatedly asked when her period was due. When her period ended, around Oct. 18, she tried to put him off by pretending that she was bleeding for nearly a week, she recalled.

Around Oct. 24, the guard, who called himself Muhammad, attacked her, she said.

Early that morning, she said, Muhammad unlocked her chain and left her in the bathroom. After she undressed and began washing herself in the bathtub, Muhammad returned and stood in the doorway, holding a pistol.

“He came towards me and shoved the gun at my forehead,” Soussana recalled during eight hours of interviews with The New York Times in mid-March. After hitting Soussana and forcing her to remove her towel, Muhammad groped her, sat her on the edge of the bathtub and hit her again, she said.

He dragged her at gunpoint back to the child’s bedroom, a room covered in images of cartoon character SpongeBob SquarePants, she recalled.

“Then he, with the gun pointed at me, forced me to commit a sexual act on him,” Soussana said.

Soussana, 40, is the first Israeli to speak publicly about being sexually assaulted during captivity after the Hamas-led raid on southern Israel. In her interviews with the Times, conducted mostly in English, she provided extensive details of sexual and other violence she suffered during a 55-day ordeal.

Soussana’s personal account of her experience in captivity is consistent with what she told two doctors and a social worker less than 24 hours after she was freed Nov. 30. Their reports about her account state the nature of the sexual act; the Times agreed not to disclose the specifics.

Soussana described being detained in roughly a half-dozen sites, including private homes, an office and a subterranean tunnel. Later in her detention, she said, a group of captors suspended her across the gap between two couches and beat her.

For months, Hamas and its supporters have denied that its members sexually abused people in captivity or during the Oct. 7 terrorist attack. This month, a United Nations report said that there was “clear and convincing information” that some hostages had suffered sexual violence and that there were “reasonable grounds” to believe sexual violence occurred during the raid, while acknowledging the “challenges and limitations” of examining the issue.

After being released along with 105 other hostages during a cease-fire in late November, Soussana spoke only in vague terms publicly about her treatment in the Gaza Strip, wary of recounting such a traumatic experience. When filmed by Hamas minutes before being freed, she said, she pretended to have been treated well to avoid jeopardizing her release.

Soussana said she had decided to speak out now to raise awareness about the plight of the hostages still in Gaza, whose number has been put at more than 100, as negotiations for a cease-fire falter.

Hours after her release, Soussana spoke with a senior Israeli gynecologist, Dr. Julia Barda, and a social worker, Valeria Tsekhovsky, about the sexual assault, the two women said in separate interviews with the Times. A medical report filed jointly by them, and reviewed by the Times, briefly summarizes her account.

“Amit spoke immediately, fluently and in detail not only about her sexual assault but also about the many other ordeals she experienced,” Barda said.

The following day, Dec. 1, Soussana shared her experience with a doctor from Israel’s National Center of Forensic Medicine, according to the center’s medical report, which was reviewed by the Times.

Siegal Sadetzki, a professor at Tel Aviv University medical school who is helping and advising Soussana’s family as a volunteer, said Soussana first told her about the sexual assault within days of her release. Sadetzki, a former top Israeli health official, said Soussana’s accounts have remained consistent.

I didn’t want to let them take me to Gaza like an object, without a fight.

Soussana also spoke to the U.N. team that published the report on sexual violence, but the Times was unable to review her testimony.

A spokesperson for Hamas, Basem Naim, said in a 1,300-word response to the Times that it was essential for the group to investigate Soussana’s allegations but that such an inquiry was impossible in “the current circumstances.”

Naim cast doubt on Soussana’s account, questioning why she had not spoken publicly about the extent of her mistreatment. He said the level of detail in her account makes “it difficult to believe the story, unless it was designed by some security officers.”

“For us, the human body, and especially that of the woman, is sacred,” he said, adding that Hamas’ religious beliefs “forbade any mistreatment of any human being, regardless of his sex, religion or ethnicity.”

Naim criticized the Times for insufficient coverage of Palestinian suffering, including reports of sexual assault by Israeli soldiers on Palestinian women, which have been the subject of investigations by U.N. officials, rights groups and others. He also said “civilian hostages were not the target” of the raid and added, “We have from the first moment declared our readiness to release them.”

A Hamas planning document found in one village shortly after the Oct. 7 raid, which was reviewed by the Times, said, “Take soldiers and civilians as prisoners and hostages to negotiate with.” Video from Oct. 7 shows uniformed Hamas militants abducting civilians.

The Abduction

Soussana lived alone in a cramped single-story home on the western side of Kibbutz Kfar Azza. After hearing sirens warning of rocket attacks Oct. 7, she said, she sheltered in her bedroom, which was also a reinforced safe room.

From her bedroom, Soussana listened as the attackers’ gunfire grew closer.

The small kibbutz stands roughly 1.5 miles from Gaza, and it was one of more than 20 Israeli villages, towns and army bases overrun that day by thousands who surged across the Gaza border shortly after dawn. Some 1,200 people were killed that day and about 250 abducted, Israeli officials say, setting off a war in Gaza that local health officials say has killed at least 31,000 Palestinians.

Soussana was at the kibbutz almost by chance. Sick with a fever, she had been recuperating the previous day in the nearby city of Sderot, with her mother, Mira, who pressed her to stay the night. But Soussana drove home to Kfar Azza to feed her three cats, she said.

The youngest of three sisters, Soussana had grown up in Sderot. She qualified as a lawyer at a local college and worked for a law firm specializing in intellectual property. Her colleagues considered her a diligent, quiet and private person who kept her distance, her supervisor, Oren Mendler, said in an interview. In Kfar Azza, Soussana said, she rarely involved herself in village life and was not part of the local WhatsApp groups, which left her unaware of the extent of the attack on the kibbutz.

At 9:46 a.m. that day, Soussana heard gunmen outside, prompting her to hide inside her bedroom closet, according to messages on her family WhatsApp group reviewed by the Times. Twenty minutes later, her phone died.

Moments later, “I heard an explosion, a huge explosion,” she said. “And the second after that, someone opened the closet door.”

Dragged from the closet, she said, she saw roughly 10 men rifling through her belongings, armed with assault rifles, a grenade launcher and a machete.

Part of the house was on fire — a blaze that would ruin the building.

Over the next hour, the group dragged her through a nearby field toward Gaza. Security footage from a solar farm near the kibbutz, which was widely circulated on the internet, shows the group repeatedly tackling her to the ground as they struggled to restrain her. At one point, a kidnapper picked her up and slung her across his back. The video shows her flailing so hard, her legs thrashing in the air, that the man tumbled to the ground.

“I didn’t want to let them take me to Gaza like an object, without a fight,” Soussana said. “I still kept believing that someone will come and rescue me.”

The Abuser

The kidnappers attempted to restrain her by beating her and wrapping her in a white fabric, the video shows. Unable to subdue her, the attackers tried and failed to carry her by bicycle, she said. Finally, they bound her hands and feet and dragged her across the bumpy farmland into Gaza, she said.

She was badly wounded, bleeding heavily, with a split lip, she said. The hospital report prepared shortly after her release said that she returned to Israel with fractures in her right eye socket, cheek, knee and nose and severe bruising on her knee and back. The report stated that several injuries were related to her abduction Oct. 7, including punches to her right eye.

After reaching the edge of Gaza, Soussana said, she was shoved into a waiting car and driven a few hundred yards into the outskirts of Gaza City. She was untied, dressed in a paramilitary uniform and transferred to another car filled with uniformed militants. A hood was placed over her head, although she could still catch glimpses of her surroundings from under it, she said. After a short drive, she was hurried up a staircase and onto a rooftop, she said.

After the hood was removed, Soussana said, she found herself in a small structure built on the roof of what she would later realize was an upscale private home. She remembered that militants were busy taking more guns from a box. Then the gunmen hurried downstairs, and she was left alone, facing a wall, with a man who said he was the owner of the house and called himself Mahmoud, she recalled.

“After a couple of minutes, he said I can turn around,” Soussana said. “And I was shocked,” she added. “I find myself sitting in a house in Gaza.”

She said Mahmoud was soon joined by a younger man, Muhammad. She remembered Muhammad as a chubby, balding man of average height with a wide nose.

I saw the chains, and I saw that my face was all swollen and blue. And I just started to cry.

Later that day, they dressed her in a thick brown garment that covered her body, she said. They gave her three pills, which they said were painkillers. It was the only time that she remembers receiving any kind of medicine in Gaza, let alone medical treatment.

Fitted with a fan and a television, the room appeared to have been prepared for her arrival, she said. There were three mattresses, she said, one for her and two for the guards.

Early in her captivity, her guards chained her ankle to the window frame, she said. Around Oct. 11, she said, she was led by the chain to a bedroom downstairs. She understood that it belonged to one of Mahmoud’s sons and that his family had been moved to another place.

The chain was reattached to the door handle, she said, next to a mirror. For the first time since her capture, she could see what she looked like.

“I saw the chains, and I saw that my face was all swollen and blue,” she said.

“And I just started to cry,” she said. “This was one of the lowest moments of my life.”

The Jail

For the next 2 1/2 weeks in October, Soussana said, she was guarded exclusively by Muhammad.

She recalled that the room was almost permanently shrouded in darkness. The curtain was usually drawn shut, and there were rolling power outages for most of the day, she said.

She said Muhammad slept outside the bedroom, in the adjacent living room, but frequently entered the bedroom in his underwear, asking about her sex life and offering to massage her body.

When he took her to the bathroom, Soussana said, he refused to let her shut the door. After giving her sanitary pads, Muhammad seemed particularly interested in the timing of her period, she said. She said she had spoken in a mix of basic English and Arabic; she had learned a little Arabic at school, and her mother’s family — Jews from Iraq — had sometimes spoken it during her childhood.

“Every day, he would ask, ‘Did you get your period? Did you get your period? When you get your period, when it will be over, you will wash; you will take a shower, and you will wash your clothes,’” Soussana recalled.

When it arrived, Soussana said, she was exhausted, afraid and undernourished; her period lasted just one day. She managed to convince him that her menstruation continued for nearly a week, she said.

She tried to humanize herself in his eyes by asking the meaning of Arabic words she heard on television. She also promised that her family would reward him financially if she was returned without further harm to Israel, she said.

In the afternoons, two associates of Muhammad would join him at the apartment, bringing him a cooked meal, she said. Some of this food was given to her as her one meal of the day.

The Israeli strikes on the neighborhood became more frequent and frightening, Soussana said, noting that some shattered the windows. As the bombing intensified, she said, she started feeling sorry for the civilians, wondering why Hamas had never built bomb shelters for its people.

“I felt for them,” Soussana said. “Just think about growing up like this; it’s scary.”

The Assault

Early on the morning of the assault, she said, Muhammad insisted she take a shower, but she refused, saying the water was cold. Undeterred, he unchained Soussana and brought her to the kitchen and showed her a pot of water boiling on the stove, she said.

Minutes later, he brought her to the bathroom and gave her the heated water to pour over herself, she said.

After washing for a few minutes, she heard his voice again from the door, she said.

“‘Quickly, Amit, quickly,’” she recalled him saying.

“I turned around, and I saw him standing there,” she said. “With the gun.”

She remembered reaching for a hand towel to cover herself as he advanced and hit her.

“He said, ‘Amit, Amit, take it off,’” she recalled. “Finally, I took it off.”

“He sat me on the edge of the bath. And I closed my legs. And I resisted. And he kept punching me and put his gun in my face,” Soussana said. “Then he dragged me to the bedroom.”

At that point, Muhammad forced her to commit a sexual act on him, Soussana said. After the assault, Muhammad left the room to wash, leaving Soussana sitting naked in the dark, she said.

When he returned, she recalled him showing remorse, saying, “I’m bad. I’m bad. Please don’t tell Israel.”

That day, Muhammad repeatedly returned to offer her food, Soussana said. Sobbing on the bed, she turned down the initial offerings, she said.

Knowing that Soussana craved sunlight, she said, he refused to open the curtains, leaving the room in darkness. Desperate for daylight, she accepted the food, believing that she had no other option but to placate her abuser.

“You can’t stand looking at him, but you have to. He’s the one who’s protecting you. He’s your guard,” she said. “You’re there with him, and you know that every moment, it can happen again. You’re completely dependent on him.”

The Israelis

Soussana said her captors moved her away from the border after a major, hourslong bombardment overnight. Based on the extent of the explosions and snippets she caught on television, she later concluded it was around the start of Israel’s ground invasion of Gaza on Friday, Oct. 27.

On the following day, she was hurried into a small white car, she said. The driver headed southwest toward what she would later be told was the central city of Nuseirat.

“Muhammad is sitting in the back seat next to me, and with the gun pointed at me,” she said.

The car stopped outside what looked like a U.N. school, and Soussana was ushered into a busy street, she recalled.

She said she was handed over to a man who called himself Amir. He marched her up the stairs of a nearby apartment block and into another private home, she said.

For the first time in weeks, she was free of Muhammad — but terrified to be entering yet another unknown. “‘Oh, my God,’” she remembered wondering. “‘What’s going to happen to me?’”

The man ushered her into a bedroom and shut the door behind her, she recalled. Inside, she found two young women playing cards, next to an older man lying on a bed and an older woman sitting in a chair, she said. Soussana was wearing traditional clothes from Gaza, she recalled.

“They looked at me, and I looked at them for, like, half a minute,” she said. “Then I asked, ‘Are you Israelis?’”

“Are you Israeli?” Soussana remembered one of the women replying.

The Tunnels

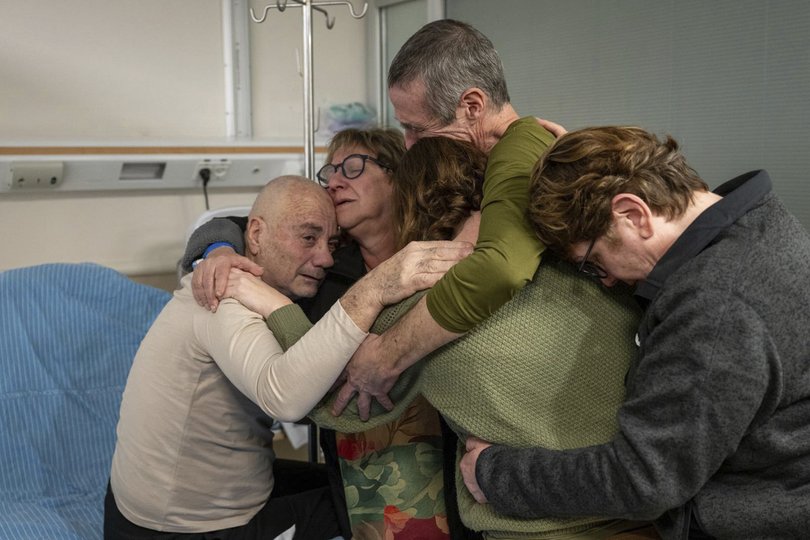

Three weeks after her kidnapping, Soussana had been united with four other hostages. Hugging them, Soussana broke down in tears, she said.

The identities of the four others were shared with the Times on the condition that their names would not be used, to protect those still in captivity.

A few days after her arrival, she was summoned to the apartment’s living room, Soussana recalled. Amir often played here with his children.

On that day, the guards wrapped her head in a pink shirt, forced her to sit on the floor, handcuffed her and began beating her with the butt of a gun, she said.

After several minutes, they used duct tape to cover her mouth and nose, tied her feet and placed the handcuffs on the base of her palms, she said. Then she was suspended, hanging “like a chicken” from a stick stretching between two couches, causing her such pain that she felt that her hands would soon be dislocated.

They carried on beating and kicking her, focusing on the soles of her feet, while simultaneously demanding information they believed she was hiding from them, Soussana said.

She still doesn’t understand what exactly they wanted or why they thought she was concealing something, she said. At one point, the head guard brought over a spike and made as if to poke her eye with it, pulling away just in time, she said.

“It was like that for 45 minutes or so,” she said. “They were hitting me and laughing and kicking me, and called the other hostages to see me,” she said.

Soussana recalled that the kidnappers untied her and returned her to the bedroom, telling her she had 40 minutes to produce the information they wanted, or else they would kill her. She said one of the young women was so frightened that she asked Soussana if she had any last messages for her family.

In mid-November, the hostages were separated: The two youngest women were taken to an unknown location, she said, while Soussana and the older couple were driven to a house surrounded by farmland.

They found the house full of gunmen, who ordered them to sit on the floor. Suddenly, the older woman began to scream, Soussana said.

The woman was looking into a shaft that descended into the ground, Soussana said. “I hear one of the drivers telling her, ‘Don’t worry, don’t worry. It’s a city down there.’”

“Then I realized,” Soussana said. “We’re going into the tunnels.”

The Release

A ladder, several stairs and a series of narrow, sloping passageways led the three hostages deep underground, she said.

By the time they reached the bottom, the guards said they were 40 meters (more than 130 feet) deep, something they hoped would reassure the hostages, she said: The Israeli bombs could not reach them there.

Soussana said a big gunman in a mask was waiting for them at the bottom. Initially, he started shouting at them, telling them that Israel had killed his family, she said, but then quickly stopped, removed his mask and took a different tone.

She said the man introduced himself in English as Jihad and told them his father had worked in Israel and had even had his Israeli boss to dinner, in the years when Israeli civilians could still enter Gaza. He spoke in Hebrew at times. Jihad said he had learned some from watching Israeli television and sang them a famous song that he had heard on a children’s show, Soussana remembered.

“I was shocked,” Soussana said. “Suddenly, he was the most humane guy we met there.”

The ground shook every time a missile struck nearby, making her fear they might be buried alive, she said. The tunnels were dark, damp and too narrow for two people to pass each other. And their subterranean cell was so short of air that they were left dizzy and panting after taking a few steps, she said.

Israeli troops would later capture and photograph the tunnel. Soussana identified fabrics and mattresses in the pictures.

Their captors spent little more than an hour a day in the tunnel, ascending to higher levels overnight for fresh air, Soussana said. The hostages pleaded with the guards to bring them, too.

After several days, the kidnappers gave in, brought them back to the surface and drove them to another private house, Soussana said.

They were still there when Israel and Hamas agreed to a hostage deal and a temporary truce, which went into force Friday, Nov. 24. The following day, the three hostages were driven to an office in Gaza City — Soussana’s final detention site.

Every day brought hope and disappointment. It was never clear which hostages would be freed or when.

On Thursday, Nov. 30, which turned out to be the last full day of the truce, the guards were making lunch when one of them finished a phone call and turned to Amit.

“He says, ‘Amit. Israel. You. One hour,’” Soussana recalled.

Within an hour, Soussana said, she was separated from the older hostage and driven through Gaza City. The car stopped, and a woman in a hijab climbed inside. It was another Israeli hostage: Mia Schem, who was also being released.

They were taken to a junkyard, Soussana recalled. Around them, she said, their guards changed from civilian clothes into uniforms.

Finally, the two women were driven to Palestine Square, a major plaza at the heart of Gaza City, where a raucous crowd waited to see them handed over to the Red Cross. Social media video showed that Hamas struggled to control the onlookers, who surrounded the car, pressed up against its windows and at one point began to rock the vehicle, Soussana said.

After a tense few minutes, the Red Cross officials managed to transfer the women to their jeep.

As they approached the Israeli border, a female Red Cross official handed Soussana a phone. A person who said he was a soldier greeted her in Hebrew.

“He said, ‘A couple more minutes, and we’re going to meet you,’” Soussana said. “I remember I started to cry.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2024 The New York Times Company

If you or someone you know needs help, contact 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732), or Sexual Assault Counselling Australia on 1800 211 028, the WA Sexual Assault Resource Centre on 6458 1828 or 1800 199 888 or Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Originally published on The New York Times