THE WASHINGTON POST: These Iran nuclear sites are the focus of Israel’s attacks

THE WASHINGTON POST: Here’s what we know about the Iranian sites that Israel has attacked so far, why they are so difficult to destroy and what nuclear hazards the strikes could pose.

Preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons has been the primary goal of US and Israeli policy toward Iran for decades.

The Iranian nuclear program has existed in some form since the 1950s, when Iran was ruled by a US-backed monarchy and Washington supported the development of an Iranian civil nuclear sector.

After the 1979 Islamic revolution, the newly formed Islamic Republic of Iran turned toward Russia and China to build its nuclear capabilities. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, Iran openly pursued nuclear weapons research but declared that it would halt its nuclear weapons program in 2003.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Since then, Iran’s civil nuclear program has continued, although it was limited by the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, known as the Iran nuclear deal, from 2015 until a year after President Donald Trump’s unilateral withdrawal in 2018.

Iran claims it is interested in developing nuclear reactors only for civilian energy use, but analysts - and Western governments - long have contended that Tehran is intent on obtaining nuclear weapons.

On Friday, Israel launched a wave of strikes on Iran, including on its nuclear facilities. Here’s what we know about the sites that Israel has attacked so far, why they are so difficult to destroy and what nuclear hazards the strikes could pose.

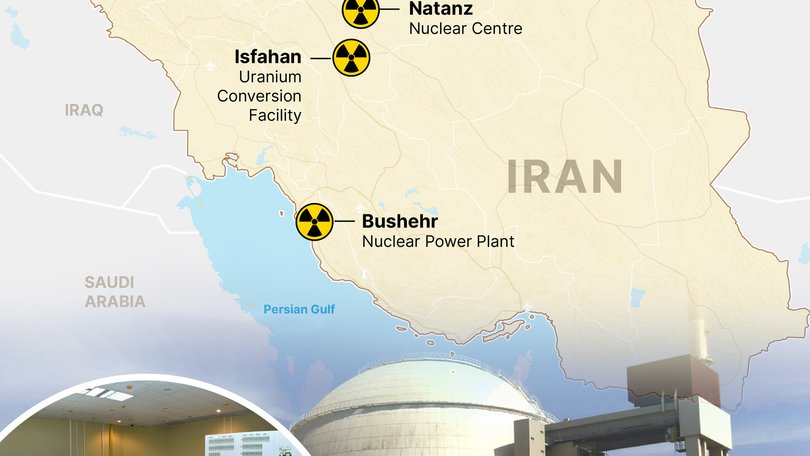

Natanz nuclear facility

Iran boasts two facilities that enrich uranium gas using centrifuges, producing the uranium fuel to power civilian nuclear reactors - and without which Iran cannot build nuclear weapons.

Taking out both sites is a critical goal for Israel.

Israel struck Iran’s main uranium enrichment site, the Natanz nuclear facility, in the first wave of attacks Friday.

Built in secret but publicly revealed in 2002, Natanz is capable of enriching uranium to 60 percent purity, Iran said in 2021 - close enough to the 90 percent purity required for weapons-grade uranium - and is thought to be responsible for producing most of Iran’s near weapons-grade uranium, given that it houses far more centrifuges than Iran’s other enrichment facility.

Natanz, located more than 160km south-east of Tehran, lies partially underground and partially above ground, making it a relatively more accessible target for airstrikes and bombings.

The Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran confirmed that the Israeli attacks had damaged Natanz and that chemical and radiation pollution had been detected inside the facility. Though the extent of the destruction remains unclear, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the UN nuclear watchdog, said Tuesday that the underground portion of Natanz, which contains the centrifuges, had been directly struck. The Natanz centrifuges were “severely damaged if not destroyed altogether,” IAEA head Rafael Grossi told the BBC on Monday.

Operation Rising Lion is not the first attack on Natanz.

Stuxnet, a malicious computer virus described by US officials as an Israeli-American joint operation, sabotaged Natanz’s centrifuges in 2010. Two separate explosions in 2020 and 2021 also damaged the facility.

Iran blamed Israel, which has not confirmed playing any role in the incidents. Natanz was repaired following each attack.

Fordow fuel enrichment plant

The existence of Iran’s second nuclear enrichment site Fordow was publicly confirmed in 2009 after Iran built it in secret.

Fordow is ostensibly designed to produce uranium enriched to 20 per cent purity, but IAEA inspectors found samples of uranium enriched to 83.7 percent purity in the facility in March 2023.

A former Iranian missile base about 160 km south of Tehran near the city of Qom, Fordow is dug into a mountainside hundreds of feet belowground.

Though Fordow houses fewer centrifuges than Natanz, the facility’s subterranean design renders it far less vulnerable to airstrikes.

Israel did not include Fordow in its initial round of attacks but launched airstrikes in the vicinity of the site hours after it hit Natanz, Iranian authorities told the IAEA.

The IAEA has not detected signs of damage at Fordow, Mr Grossi said Monday.

Analysts say Fordow could be destroyed by multiple GBU-57 A/B Massive Ordnance Penetrator bombs, known as “bunker busters,” which use massive force to destroy targets deep underground.

Israel has neither the bombs nor the planes needed to lift the heavy explosives. The US possesses both.

Isfahan nuclear technology centre

Isfahan houses the plant where natural uranium is converted into the uranium hexafluoride gas that is fed into centrifuges at Natanz and Fordow, according to the Washington-based Nuclear Threat Initiative.

Israel struck Isfahan on Friday, and Grossi confirmed Sunday the attack had damaged four buildings, including the uranium conversion facility.

Iran said on Thursday - before the Israeli strikes - that it would begin plans to build a third enrichment site. The announcement came in response to the IAEA’s first-ever censure of Iran’s nuclear program, which found that the country had failed to comply with nonproliferation obligations and came with the threat of sanctions.

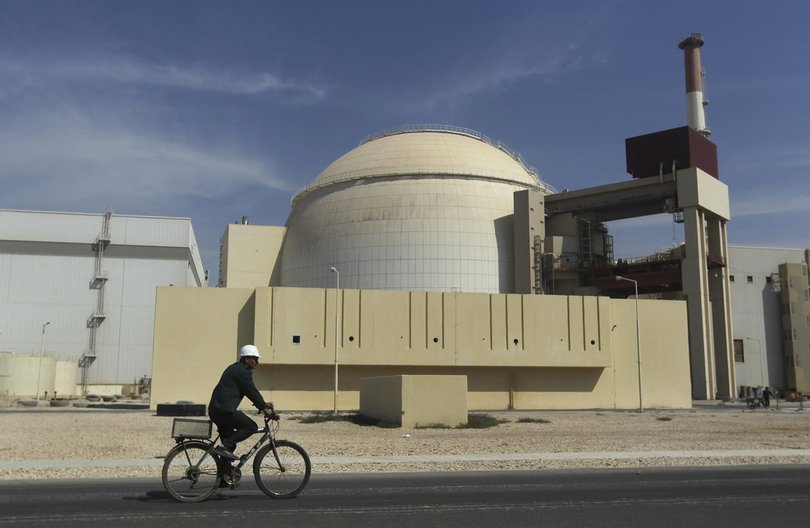

Nuclear power plants

Iran’s nuclear program also includes the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant, a commercial nuclear reactor in the south near the Persian Gulf, and the Tehran Nuclear Research Centre, which contains a small research reactor supplied by the US to the previous Iranian regime in 1967.

The greatest risk of nuclear fallout - radioactive particles released into the atmosphere - would come if Israel chose to attack one of Iran’s nuclear reactors.

Material from the reactor itself, or spent fuel being stored in cooling tanks at those sites, could create the kind of accident that took place at Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in the Soviet Union in 1986 or Japan’s Fukushima power plant in 2011.

“With Iran, the facilities that we are most concerned about are the operating power plants, with Bushehr at the top of the list,” said Nickolas Roth, NTI’s senior director of nuclear materials security.

Fear of nuclear hazards amid Israeli strikes

Arab governments in the region, including Qatar, expressed concern about the possibility of nuclear fallout.

One official in the Persian Gulf, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive matter, said their government was most worried about a strike on nuclear sites inadvertently triggering an explosion that disperses nuclear material in the region.

Still, nuclear experts say that attacks on Iran’s buried enrichment facilities, or on stored highly enriched uranium, pose little radiation risk to those outside because of the nature of the material itself and the likelihood it would not travel far.

“The radiation, primarily consisting of alpha particles, poses a significant danger if uranium is inhaled or ingested,” a risk that can be mitigated by protective devices for those in the facility, Mr Grossi told the IAEA board of governors Monday.

“However, this risk can be effectively managed with appropriate protective measures such as using respiratory protection devices while inside the affected facilities.”

What is more immediately concerning is the release of a plume of toxic chemicals that can form if and when the uranium material, most of which is stored as uranium hexafluoride gas, comes into contact with water in the form of humidity in the air. That leads to the formation of hydrofluoric acid, an extremely hazardous gas.

“Talk about these facilities becoming dirty bombs and that sort of thing, it’s not supported by science,” said Edwin Lyman, director of nuclear power safety at the Nuclear Threat Initiative. “But the chemical hazards are very real.”

The greatest risk of strikes would be to workers in the vicinity of the facility. Both Fordow and Natanz are fairly far from populated areas, and the gas would dissipate within a few kilometers of the site.

The extent of the danger also would depend on the explosion, whether it collapsed the mountain under which Fordow was buried, effectively containing dangerous materials from escaping into the air, or created a crater, Mr Lyman said.