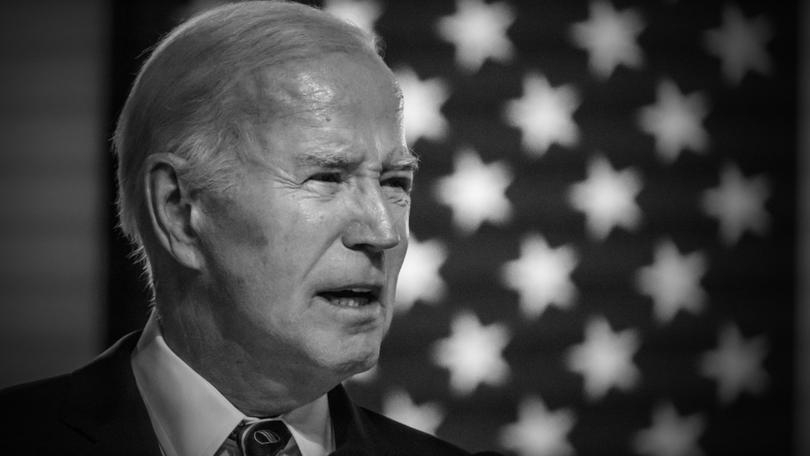

The New York Times: What if Joe Biden Is Actually Right About 2024?

‘Biden’s address performed a crucial civic service, not only by channeling the public’s revulsion at a flagrant narcissist who won’t take no for an answer but also by stating what may happen if he wins again.’

“What a sick … My God.”

President Joe Biden offered many eloquent turns of phrase on the importance and the fragility of democracy in his well-crafted campaign kickoff speech Friday near Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. But it was this brief, unfinished aside — off-script, sandwiched around an extended silence during which the president clenched his fists in an effort to resist uttering the curse behind his teeth — that best captured the exasperating reality he, along with a majority of the country, struggles to cope with as we enter an election year unlike any in American history.

The sick [expletive] in question is, naturally, Donald Trump, Biden’s predecessor and the likely Republican nominee for the third straight time. Just before the aside, Biden had deplored how the former president not only encourages political violence but makes a joke of it, as he did after a deranged man broke into former Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s San Francisco home in 2022 and beat her husband, Paul, with a hammer. The man had been looking for Nancy Pelosi, using the same language the Jan. 6 insurrectionists did when, incited by Trump, they stormed the Capitol three years ago.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.

Biden’s address performed a crucial civic service, not only by channeling the public’s revulsion at a flagrant narcissist who won’t take no for an answer, but also by forthrightly stating just what could happen to the United States if that narcissist wins again.

Before last week, Biden had mostly managed to avoid talking about the former president — a wise move, all things considered. Trump’s chaotic four years in office exhausted everyone, including many of his own followers. Biden would refer to his predecessor as “the former guy,” and try to switch the conversation to a more promising future rather than dwelling on the past. He had campaigned in 2020 on the promise of a return to normalcy, and he has by and large delivered on that.

But there were no euphemisms in this speech, his first of a momentous 2024, and perhaps there will not be again. Biden seemed to understand that his task now is to remind the American people of what that exhaustion felt like, and what four more years (at least) of Trump would mean for the country, and the world. Standing at George Washington’s crucible, he made it clear how much is at stake.

He also performed a service by keeping the preservation of American democracy central to his campaign. He has faced plenty of second-guessing for this choice. Democracy is a big, amorphous concept like climate change, the critics say. Regular people struggle to understand it as concretely as they do, say, crime or the economy.

But as Biden explained, “Without democracy, no progress is possible.” It’s all connected, he said.

“Democracy means having the freedom to speak your mind, to be who you are, to be who you want to be,” he said. “Democracy is about being able to bring about peaceful change. Democracy — democracy is how we’ve opened the doors of opportunity wider and wider with each successive generation, notwithstanding our mistakes. But if democracy falls, we’ll lose that freedom.”

Still the skeptics come, even purported allies like Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, who courageously bucked his party in voting to convict Trump on an impeachment charge after the insurrection. “Jan. 6 will be four years old by the election,” Romney told The New York Times last week. “People have processed it, one way or another. Biden needs fresh material, a new attack, rather than kicking a dead political horse.”

This seems naïve in the extreme. The pro-democracy message resonated in the 2022 midterms, when voters across the country clearly understood the stakes and rejected the most dangerous election-deniers.

If Trump is back on the ticket, the threat is far greater. That’s why Biden was right to warn of the danger in Trump’s making martyrs of the Jan. 6 “hostages” — his term for the hundreds of people convicted and sentenced to prison for their role in the deadly attack that he continues to celebrate (even as his allies claim it was an inside job). Jan. 6, 2021, may be 3 years old, but Jan. 6, 2025, is less than a year away.

The violence Trump unleashed on Jan. 6 was, at bottom, about his and his followers’ unwillingness to accept defeat. And yet, as Biden put it, “You can’t love your country only when you win.” At the end of his speech, he returned to the example of Washington, who gave up his military leadership and his presidency at the height of his powers.

“Our leaders return power to the people and they do it willingly because that’s the deal,” he said. But as everyone knows, Trump never agrees to any deal whose terms he didn’t set, and to his distinct personal advantage, in the first place.

This is why Biden’s speech was so necessary now. The 2024 election will not be the usual battle between parties, platforms and policies. It is a battle between those who fundamentally respect and abide by the ground rules of democracy and those who do not.

To underline his case most forcefully, Biden didn’t need to use his own words. He could rely on the words of his opponent: revenge, retribution, fight like hell, terminate the Constitution, suckers and losers, vermin, poisoning the blood of our country, dictator on Day 1, American carnage. There is no subtext here; it’s all text. As Biden put it, “We all know who Donald Trump is.”

And yet, apparently, we need to keep reminding ourselves. Otherwise, we fall into the trap of normalization that Trump laid from the start. Eight years after he railed about Mexican rapists, he has inured large swathes of the American electorate to his extremism. Today he can call for the execution of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, or tell the Biden administration to “rot in hell,” or promote a video claiming he is literally a gift from God, and it gets less attention in both mainstream and social media than Biden tripping over a sandbag.

If the blood of the country is being poisoned, this is how.

How did we end up here? Biden offered one compelling explanation: complacency. “We’ve been blessed so long with a strong, stable democracy, it’s easy to forget why so many before us risked their lives and strengthened democracy,” he said.

In that sense, democracy is like vaccines. Few people today have firsthand memories of the horrors of diseases that were rampant before vaccines largely eradicated them, which makes it easier for vaccine hesitancy to take root. Similarly, when a country has no history of living under a dictatorship, it can be easier to lose sight of what it means to live in a representative democracy, and to be caught flat-footed when a real authoritarian comes knocking.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2023 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times